The start of the UK Government’s new towns programme represents a pivotal moment, both for planning and the country’s ability to rise to the challenges it faces. In this context, and as the work of the New Towns Taskforce comes to fruition, the Royal Town Planning Institute’s Futureproof New Towns project is investigating how to ensure that the next generation of new towns are adaptable, flexible, and evolve over time to meet communities’ changing needs in an uncertain age.

The start of the UK Government’s new towns programme represents a pivotal moment, both for planning and the country’s ability to rise to the challenges it faces. In this context, and as the work of the New Towns Taskforce comes to fruition, the Royal Town Planning Institute’s Futureproof New Towns project is investigating how to ensure that the next generation of new towns are adaptable, flexible, and evolve over time to meet communities’ changing needs in an uncertain age.

You can download the report in pdf or Word format or read in full below:

The Royal Town Planning Institute

The Royal Town Planning Institute (RTPI) champions the power of planning to create prosperous places and vibrant communities. We have over 27,000 members in the private, public, academic and voluntary sectors. Using our expertise and research we bring evidence and thought leadership to shape planning policies and thinking, putting the profession at the heart of society's big debates. We set the standards of planning education and professional behaviour that give our members, wherever they work in the world, a unique ability to meet complex economic, social and environmental challenges. We are the only body in the United Kingdom that confers chartered status to planners, the highest professional qualification, sought after by employers in both the private and public sectors.

Report authors

This report was commissioned by the RTPI as part of its Futureproof New Towns project.

It was authored by the Futureproof New Towns project team, which comprises:

- Professor John Sturzaker FRTPI, University of Hertfordshire

- Professor Alex Lord, University of Liverpool

- Dr Phil O’Brien, University of Glasow

- Associate Professor Susan Parham MRTPI, University of Hertfordshire

- Ellie Pritchard, University of Hertfordshire

The RTPI Practice and Research team provided input and edited the report.

Contents

1. Introduction

1.1 A national and global challenge

1.2 The RTPI’s Futureproof New Towns project

2. Key themes from the case studies

2.1 Almere (Netherlands) – an incremental and organic new town

2.2 Freiburg (Germany) – consistency of approach brings dividends for urban design

2.3 The Paris Region (France) – a ring of new towns well connected by public transport

2.4 Chandigarh (India) – a classic icon of modernism that highlights the risks of overly deterministic master planning

2.5 Daybreak (USA) – a pioneering approach to avoiding car-based sprawl

2.6 Curitiba (Brazil) – pragmatism and flexibility to reflect changes

3. Key themes from the literature

Executive summary

The start of the UK Government’s new towns programme represents a pivotal moment, both for planning and the country’s ability to rise to the challenges it faces. The stakes are high. If successful, the next generation of new towns could drive national renewal and provide a clear demonstration of planning’s power to create flourishing communities. If unsuccessful, the costs for the environment, society and economy could be huge. Communities’ trust in the state to shape places for the better could be undermined.

Britain’s post war new towns have a mixed reputation. They transformed living standards, and more than 2.8 million people currently call them home. But their plans have also been widely criticised for ‘baking in’ then-fashionable assumptions about the future – about transport, industry, urban form, culture, retail, housing, and the environment – that have not stood the test of time.

In this context, and as the work of the New Towns Taskforce comes to fruition, the Royal Town Planning Institute’s Futureproof New Towns project is investigating how to ensure that the next generation of new towns are a success. The project focuses in particular on how to ensure they are adaptable, flexible, and evolve over time to meet communities’ changing needs in an uncertain age.

This interim report highlights key themes in the research literature and emerging lessons from the project’s six international case studies. These are:

- Almere (Netherlands) – where taking an incremental and organic approach to growth, rather than setting fixed limits through an up-front masterplan, has helped the town to meet housing demand through a community-led model.

- Freiburg (Germany) – which demonstrates the importance of a consistent and proactive approach to design features, such as energy efficiency in buildings and avoiding car-centric urban design.

- The Paris Region (France) - which demonstrates the need for new towns to be well connected to public transport.

- Chandigarh (India) – which highlights the importance of new towns being reflective of local communities’ needs and contexts.

- Daybreak (USA) – which suggests that bottom-up approaches to design are possible in new settlements that take a creative approach to engagement.

- Curitiba (Brazil) – which shows that incremental, infrastructure-focused policy interventions can be powerful, particularly where urbanisation is rapid and plans can quickly become out of date.

The RTPI will publish the full Futureproof New Towns report, including policy recommendations to government and other stakeholders, in autumn 2025. An internationally focused report will follow, to be published at the end of 2025.

1. Introduction

1.1 A national and global challenge

In many parts of the world there is a shortage of good quality new homes built in the right places.[1] The United Nations Human Settlements Programme estimates that between 1.6 billion and 3 billion people lack adequate housing,[2] and the UK Government has set a target of 1.5 million new homes to be built over the term of this parliament to address the country’s housing crisis.

Given the challenges inherent in accommodating significant numbers of homes in existing dense urban areas, new towns can be a major contributor to meeting housing need. However, it is crucial to ensure that some of the features of past new town developments that have not been successful are avoided. These include:

- A strong tendency towards mono-tenure in housing supply, meaning that the diversity seen as essential to successful places is lacking;

- Locations which are not well connected to contemporary transport networks, resulting in car-dependent development; and

- Inadequate provision of attendant services and public goods to accompany housing, with the risk that residents become isolated.

1.2 The RTPI’s Futureproof New Towns project

To meet the challenge of creating a new generation of sustainable and vibrant new towns it is essential that we learn lessons from around the world. These must concern both what has worked and, just as importantly, what has not worked - particularly in relation to new towns’ ability to meet emerging needs and unforeseen challenges.

It is within this context that the RTPI commissioned a group of experts to undertake a comprehensive review of new towns policy successes and failures across a set of international contexts in Europe, Asia, and the Americas.

The project focuses on six in-depth case studies, developed through a combination of primary and secondary research.[*] From these we will produce a series of practical policy recommendations for UK government, local government, planners and other decision makers that will play a central role in making the next generation of new towns a success.

This interim report draws on desk-based research, including online interviews, to present the emerging findings of this project.

Visits to some of the case study locations are to be undertaken over the summer of 2025 to further develop the findings and inform a more detailed analysis. This will provide the basis for an England focused recommendations report, which we will publish in autumn 2025. We will publish an internationally focused recommendations report at the end of 2025.

2. Key themes from the case studies

2.1 Almere (Netherlands) – an incremental and organic new town

In existence only since 1976, and having expanded through successive waves of development to construct a new town on reclaimed polder adjacent to Lake IJssel in the periphery of Amsterdam, Almere is now the seventh largest city in the Netherlands.[3] The context for Almere’s establishment was the policy of ‘concentrated de-concentration’, enacted in the 1970s to control sprawl, but which was ultimately seen to have led to large-scale suburbanisation.

From the 1990s onwards, Almere has both grown its employer base (to develop beyond a a commuter suburb) and diversified its housing supply. To achieve the latter objective, while the city expanded its housing stock delivered by large-scale private housebuilders (as dominant in the Netherlands as they are in the UK) during the national VINEX housebuilding programme, it also experimented with self-build housing.

In drastic contrast to earlier phases of development, when whole areas were strictly planned and built along a blueprint model, Almere’s self-build neighbourhoods have grown incrementally and according to demand, to allow adaptability to changing circumstances. Municipally owned plots have been sold to a mix of individual households, small developers, and housing associations.

In place of a strict land-use plan is a flexible and adaptable rule framework designed to avoid conflict rather than to specify form, and to allow for experimentation in aspects such as developing a local, sustainable, urban food system.[4],[5] With its development underwritten by its location in a fast-growing part of the Netherlands, Almere has sought to reshape itself from a blueprint New Town to a more organic settlement.

Satellite image of Almere

Satellite image of Vauban District, Freiburg

2.2 Freiburg (Germany) – consistency of approach brings dividends for urban design

Freiburg is a small city in the south west of Germany, close to the French and Swiss borders. It has a long history of sustainability in its planning policies, developing from opposition to a nuclear power plant in the 1970s, which led to a heightened awareness of environmental issues in the city. The city today has strong policies related to reducing carbon emissions and hence car use, with a strong priority given to other modes of transport. As a result, the proportion of journeys made by car in the city has fallen from 30% to 16%. This is the context within which the new districts of Vauban, Dietenbach and Rieselfeld have been developed since the 1990s.[6]

Key features of interest include strong community involvement,[7] something often found to be challenging in the development of new settlements. Potential residents of the districts have been closely involved in the planning of them including, for example, expressing a preference for less car parking provided adjacent to housing, with this being centralised into district parking garages. This results in an urban form which is less constrained by roads, and hence more flexible. There is likewise an approach to collective custom build, with future occupants of medium-density housing blocks having input into the design of those homes.[8]

Green infrastructure plays an important part in the districts, with this being retrofitted into the brownfield site of Vauban and integrated from the outset into the greenfield sites of Dietenbach and Rieselfeld. Planners and policymakers in Freiburg have been proactive and have worked closely with key stakeholders to deliver development, providing important lessons for others.

A photograph of a car-free neighbourhood in Vauban that is accessible for loading (taken by the project team)

2.3 The Paris Region (France) – a ring of new towns well connected by public transport

The Paris Region master plan of 1965 sought to respond to population growth in the greater Paris agglomeration by proposing eight new towns on the urban fringe of the city. Until that point Paris was strongly monocentric, as a result of economic and political centralisation, so this was seen as a radical shift in approach.[9]

Five of the originally proposed eight new towns were eventually built. These five – Cergy-Pontoise, Evry, Marne-la-Vallée, Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines and Sénart – now comprise around 7% of the circa 12 million population of the greater Paris area, and are located around 30km from the centre of the city. This is closer than the UK new towns were built to London, as the Paris Region new towns were not intended to be self-sufficient in the same way as intended (though not achieved) in the UK.

A key feature of these new towns has been a desire to avoid the high-rise social housing estates (the banlieues) characteristic of Paris by ensuring a tenure mix and integrating the provision of employment opportunities. As with UK new towns, there was significant state-led planning in their early days, with tax incentives to encourage businesses to relocate. This policy ended in the 1980s, but employment provision continued to outpace population growth.

Some of the issues facing UK new towns are mirrored in Paris, such as a poor public image and marginalisation,[10],[11] with schemes now in place to adapt the new towns to today’s context.

A key theme in the Paris Region is the interconnectivity between new towns, understood in terms of transport infrastructure but also social and economic connectivity. Transport infrastructure spatially links and economically supports the new towns, with the RER and Transilien rail networks being instrumental parts of this.[12]

Satellite image of Évry, Paris Region

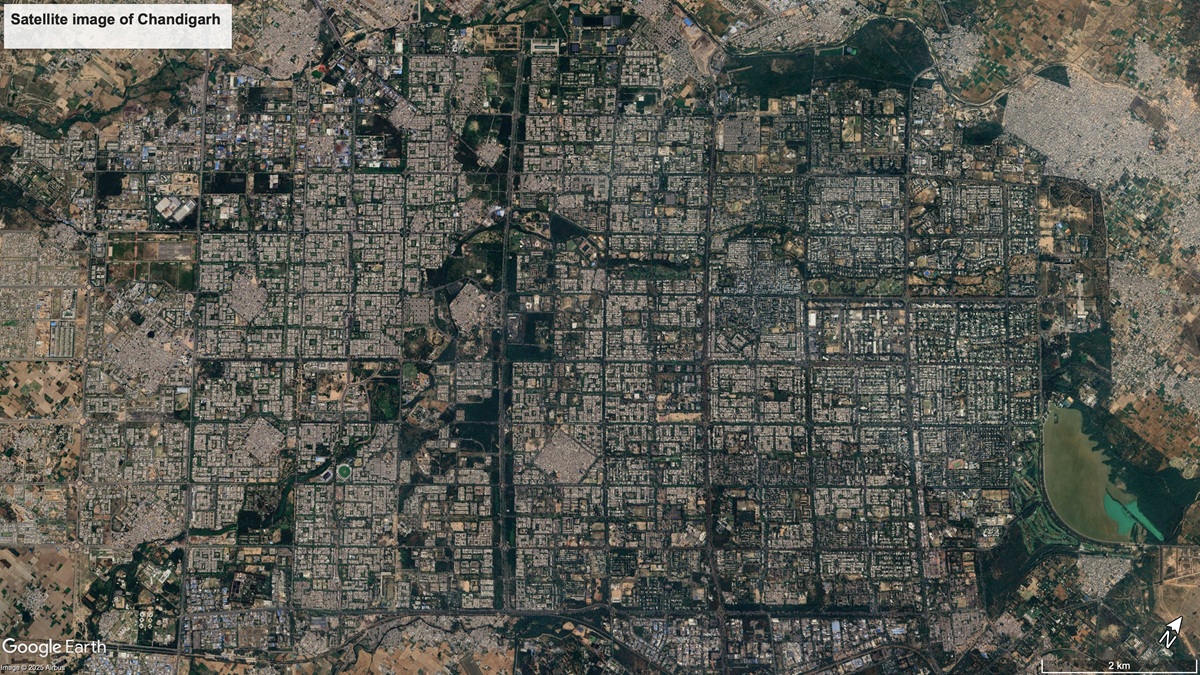

Satellite image of Chandigarh

2.4 Chandigarh (India) – a classic icon of modernism that highlights the risks of overly deterministic master planning

The Indian city of Chandigarh holds a unique place in the history of urban planning as one of India’s first post-independence planned cities. Replacing the Punjabi capital of Lahore after Partition, Chandigarh became the capital of Punjab and Haryana in 1966. The development of Chandigarh symbolised a break from traditional and conservative urban forms and represented a postcolonial, modern India.[13]

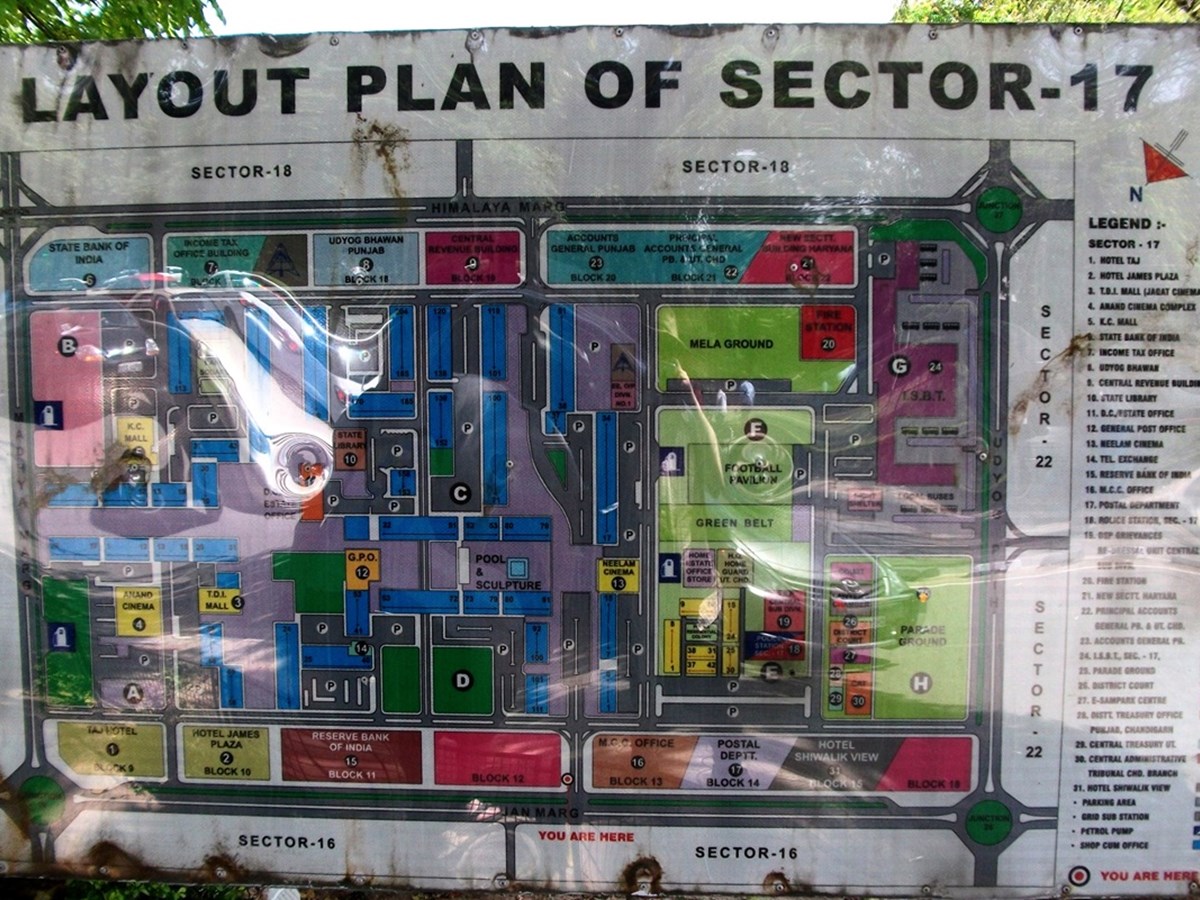

Early proposals for the city were led by Albert Mayer, but these were later redesigned by Swiss architect Le Corbusier and his team. Deeply rooted in modernist planning ideals, Chandigarh was divided into sectors which contained amenities and promoted walkability while accommodating the automobile. Le Corbusier used the metaphor of the body to describe the layout of the city with the “head” housing the Capitol Complex comprising key governmental and administrative buildings; the “heart” encompassing the commercial hub, Sector 17; and the “lungs” being green spaces integrated throughout the city.

Planning approaches sought to create a rational, orderly city, intended to embody modernist spatial logic and the Indian state’s desire to showcase a new urban identity. Sectors were intended to be self-sufficient and to have a strong sense of community and neighbourhood identity.

However, the city’s layout reflected socio-economic stratification, with urban density rising from the northern sectors to the southern ones.[14] This effectively embedded class divisions into the urban fabric, and has limited the scope to adapt the city to contemporary challenges. Chandigarh has also faced criticism for its failure to resonate with Indian social and cultural norms. The modernist emphasis on spatial order often conflicted with informal economic activities, which continue to play a significant part in the vibrant street life typical of Indian cities.

A photograph of sign in in Chandigarh that presents a map of Sector 17 (taken by the project team)

2.5 Daybreak (USA) – a pioneering approach to avoiding car-based sprawl

Daybreak, Utah, USA is located in South Jordan, approximately 30 minutes drive time from downtown Salt Lake City. It is the largest master-planned community in the history of Utah.

Originally developed by Kennecott Land, a subsidiary of mining company Rio Tinto, the development is based in an area that has historically been a centre for mineral and metals extraction. The development was taken over by Larry H Miller developments in 2021.

Currently comprising around 13,000 dwellings, there are aspirations for Daybreak to grow over the coming years to accommodate 20,000 residential units alongside around 9 million square feet of retail and commercial space, including a baseball park to accommodate the relocation of the Salt Lake Bees. The emphasis is on mixed-use development, building in adaptability to future changes. The development is, in the US context, relatively high density and well served by public transport,[15] following an influential but non-binding community engagement exercise.

At over 4,000 acres, Daybreak covers a significant area of land. Through our further analysis the research team will explore the degree to which the density of development in this context is an example for elsewhere. They will also look at the tenure mix that the developer is pursuing and the extent to which affordable homes are likely to be part of the ongoing development.

Satellite image of Daybreak

Satellite image of Central Curitiba

2.6 Curitiba (Brazil) – pragmatism and flexibility to reflect changes

Curitiba, in southern Brazil, is a settlement whose significant expansion has, since the early 1970s, been closely planned. The city’s era of planned growth began with the proposal to replace an obsolete postwar strategic plan in the mid-1960s. A new plan, authored by a team of architects influenced by the emerging ideas of Jane Jacobs and Jan Gehl,[16] was then adopted in 1971.

This new plan emphasised the human scale and alternatives to car-based transport. In doing so it contradicted the still-dominant modernist and car-focussed planning evident elsewhere in Brazil. Instead it structured the future of Curitiba around a rapid bus transit system as an affordable public transport solution, as well as the creation of parks and lakes to provide recreation space and solve the city’s repeated floods, and the extension of waste and recycling services into informally developed areas.[17]

The content of the planning approach has been focused and pragmatic, while the plan-implementation process has allowed for flexibility, combining a long-term strategic vision realised through incremental interventions and decision-making adjusted to circumstances. This is evident in the city’s decision to maintain carbon sinks on open land surrounding the city by using subsidies and transferrable development rights to maintain private land as public parks.[18] Here, a new planning goal (keeping carbon in the ground) is combined with an existing goal (creating parkland) through new policy instruments (subsidies and transferrable development rights).

3. Key themes from the literature

There is a rich seam of research literature on new towns, including that which refers to new settlements or new communities more broadly. We summarise key themes from such work below.

- New towns are seen as sites of urban experimentation, particularly in relation to being testing grounds for innovative urban design.[19],[20],[21] The outcomes of such experiments have varied, for example authors observe that such experimentation often led to long-term challenges regarding build quality and maintenance, and challenges around adapting housing to today’s needs. Today, the potential for experimentation may be for new town development to carefully interface with wider public policy innovation. See, for example, Milton Keynes, which is a test bed for ideas on placemaking futures.[22]

- The social and cultural lived experiences of residents are important but often overlooked in how we consider and discuss new towns. Residents’ perceptions are important in tackling the “anti-suburban myth” and negative associations of new towns held by some.[23],[24] These perspectives are also essential in understanding how people use spaces in new towns and how this usage has evolved over time.[25]

- New towns can be seen as political and ideological projects. Some understand new towns as a manifestation of utopian and modernist planning ideologies.[26],[27] It has further been argued that new towns were technocratic solutions to goals of modernisation, making them vulnerable to political and cultural shifts.[28] Milton Keynes (perhaps the most well-known of all UK new towns) has been used as a case study to explore tensions between different eras of government priorityand to demonstrate successful adaptation to changing circumstances.[29] Amidst uncertainty about long-term social, environmental and economic changes, it is crucial that a new generation of new towns are adaptable and flexible.

- Research highlights the challenges and limitations of modernist planning. New towns were often based on the idealistic principles of their times. This could result in a lack of flexibility in design, leading to mismatches with their inhabitants’ needs with regard to housing and social facilities. Notable studies critique modernist planning assumptions and show how communities resisted and reinterpreted spatial rules which planners sought to impose upon them.[30]

While strategies for community participation have evolved greatly since the post-war period, the meaning of participation in a planned community that is yet to be realised remains ambiguous. The next generation of new towns offer the possibility to test and develop a strong precedent for approaches to ongoing co-design and feedback sharing with inhabitants.

- The importance of new towns’ heritage in their renewal and adaptation to future challenges. Despite decline, new towns still hold untapped potential for regeneration, sustainability, and community innovation.[31],[32] Some have proven more effective than others in adapting to contemporary needs.

4. Conclusions

This short report illustrates the breadth of international experience with new towns which can be drawn upon by planners and policymakers in the UK and internationally.

Over the summer of 2025 the Futureproof New Towns research team will be undertaking visits to some of the places discussed and deepening our understanding of what makes them work and where planning challenges remain. For now, there are clear lessons to be drawn from each of the six case studies in relation to adaptation and flexibility.

From Almere, we see the benefits of an incremental and community-focused approach to growth, allowing the town to grow organically over time. The Parisian new towns remind us of the importance of strong public transport connectivity, perhaps made easier by their proximity to central Paris. The new communities in and around Freiburg highlight the importance of a consistent and proactive approach to new development, giving confidence to developers. Chandigarh, a classic modernist New Town, has perhaps fallen prey to a top-down approach, overlooking local needs, reflecting the context of its construction. Daybreak, in contrast, has been developed through a wide-ranging engagement approach that has led to more sustainable outcomes. And Curitiba illustrates that pragmatism is important, particularly in contexts of rapid urbanisation.

In many ways, the development of England’s ‘new’ new towns represents an inflection point for British policymaking. As the UK Government considers the recommendations of the New Towns Task Force, the stories that emerge from these case studies provide timely reminders of the needs for flexibility and adaptability in new town development, and a sense of how this can be achieved. These stories also provide a foundation for the more in-depth analysis to come from the Futureproof New Towns project, which we hope will enable the delivery of flourishing and sustainable new communities.

For more information:

www.rtpi.org.uk/policy-and-research/research-and-practice

References

[*] The case studies selected for analysis in this project were chosen to reflect some of the diversity in experience from around the world, and to represent different stages in the development cycle – some newer and some more well established. We recognise that there are many other interesting case studies, and our selection of these six cases should not be taken as endorsement of the approach to planning used in each case.

[1] UN-Habitat, ‘The first session of the open-ended Intergovernmental Expert Working Group[ on Adequate Housing for All’, United Nations (2024) <https://unhabitat.org/meetings/first-session-of-the-open-ended-intergovernmental-expert-working-group-on-adequate-housing-for-all> [accessed on 16/07/2025]

[2] UN-Habitat, ‘State efforts to progressively realize adequate housing for all’, United Nations (2024) <https://unhabitat.org/sites/default/files/2024/10/2416772e.pdf> [accessed on 30/07/2025]

[3] Sebastian Dembski, Olivier Sykes, Chris Couch, Xavier Desjardins, David Evers, Frank Osterhage, Stefan Siedentop and Karsten Zimmermann, K. ‘Reurbanisation and suburbia in Northwest Europe: a comparative perspective on spatial trends and policy approaches’, Progress in Planning, 150 (2021), p1-47

[4] Stefano Cozzolino, Edwin Buitelaar, Stefano Moroni and Niels Sorel ‘Experimenting in urban self-organisation: framework rules and emerging orders in Oosterwold (Almere, the Netherlands)’, Cosmos + Taxis, 4.2 (2017), p49-59

[5] Jan E. Jansma, Sigrid C. O. Wertheim-Heck, ‘Feeding the city: A social practice perspective on planning for agriculture in peri-urban Oosterwold, Almere, the Netherlands’, Land Use Policy, 117 (2022), 106104

[6] Anna Growe and Tim Freytag, ‘Image and implementation of sustainable urban development: Showcase projects and other projects in Freiburg, Heidelberg and Tübingen, Germany’, Raumforschung und Raumordnung, 77.5 (2019), p457–474

[7] Eirini Kasioumi, ‘Sustainable urbanism: Vision and planning process through an examination of two model neighborhood developments’, Berkeley planning journal, 24.1 (2011), p91–114

[8] Iqbal Hamiduddin, Social sustainability, residential design and demographic balance: neighbourhood planning strategies in Freiburg, Germany, Town Planning Review 86.1 (2015), p29-52

[9] Didier Desponds and Elizabeth Auclair, ‘The new towns around Paris 40 years later: New dynamic centralities or suburbs facing risk of marginalisation?’, Urban Studies, 54.4 (2017), p862-877

[10] European Commission, ‘Grand Paris Sud: A tailor-made city renewal’, European Commission <https://culture.ec.europa.eu/cultural-and-creative-sectors/architecture/living-spaces/catalogue/grand-paris-sud> [accessed 16/07/2025]

[11] Didier Desponds and Elizabeth Auclair, ‘The new towns around Paris 40 years later: New dynamic centralities or suburbs facing risk of marginalisation?’, Urban Studies, 54.4 (2017), p862-877

[12] Anton Salov and Elena Semerikova, ‘Transportation and urban spatial structure: Evidence from Paris’, Environment and Planning B: Urban Analytics and City Science, 51.6 (2024), p1248-1273

[13] Peter Fitting, ‘Urban Planning/Utopian Dreaming: Le Corbusier’s Chandigarh Today’, Utopian Studies, 13.1 (2002), p69–93

[14] Preetika Sharma, Kanchan Gandhi and Anu Sabhlok, ‘Queering utopia: Pride walks in modernist Chandigarh’, Urban Studies, 60.14 (2023), p2799–2815

[15] Robert Steuteville, ‘Downtown Daybreak opening a mixed-use urban centre’, Public Square, 2025 <https://www.cnu.org/publicsquare/2025/03/11/downtown-daybreak-opens-mixed-use-city-core> [Accessed on 16/07/2025]

[16] Joseli Macedo, ‘Planning a sustainable city: the making of Curitiba, Brazil’, Journal of Planning History, 12.4 (2013), p334-353

[17] Maria Elena Zingoni De Baro, Regenerating Cities: Reviving Places and Planet. (Cham, Switzerland, Springer, 2022)

[18] Hanna-Ruth Gustafsson and Elizabeth A. Kelly, ‘Developing the sustainable city: Curitiba as a Case Study’, in The Sustainable Urban Development Reader, 4th Ed. ed. by Stephen M. Wheeler (Abingdon: Taylor and Francis, 2022) p81-96

[19] Anthony Alexander, Britain’s New Towns: Garden Cities to Sustainable Communities (Abingdon, Routledge, 2009)

[20] Boughton, John, Municipal Dreams: The Rise and Fall of Council Housing (London, Verso, 2019)

[21] Emily Cole and Elain Harwood, The New Town Centre, Stevenage, Hertfordshire: Architecture and Significance (Research Report No. 267/2020, London, Historic England, 2021)

[22] ‘Reimagining urban innovation, in Haste: The slow politics of climate urgency, ed. by Håvard Haarstad, Jakob Grandin, Kristin Kjærås, and Eleanor Johnson (London: UCL Press, 2023) p200-210

[23] Mark Clapson, Invincible Green Suburbs, Brave New Towns: Social Change and Urban Dispersal in Post-War England (Manchester, Manchester University Press, 1998)

[24] Colin Ward, New Town, Home Town: The Lessons of Experience (London, Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, 1993)

[25] Lauren Pikó, Milton Keynes in British Culture: Imagining England (Abingdon, Routledge, 2020).

[26] Jane Hobson, New Towns, the Modernist Planning Project and Social Justice (London, The Bartlett Development Planning Unit, University College London, 1999)

[27] Rosemary Wakeman, Practicing Utopia: An Intellectual History of the New Town Movement (Chicago, The University of Chicago Press, 2016)

[28] Sam Wetherell, Foundations: How the Built Environment Made Twentieth-Century Britain (Princeton, Princeton University Press, 2020)

[29] Guy Ortolano, Thatcher’s Progress: From Social Democracy to Market Liberalism through an English New Town (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2019)

[30] Jane Hobson, New Towns, the Modernist Planning Project and Social Justice (London, The Bartlett Development Planning Unit, University College London, 1999)

[31] Katy Lock and Hugh Ellis, New Towns: The Rise, Fall and Rebirth (London, RIBA Publishing, 2020)

[32] Emily Cole and Elain Harwood, The New Town Centre, Stevenage, Hertfordshire: Architecture and Significance (Research Report No. 267/2020, London, Historic England, 2021)