There are around 850,000 people living with dementia in the UK. This figure is projected to increase to 1.6 million people by 2040. People living with dementia may experience the built environment differently to other people. Evidence has shown that good quality housing and well-planned, enabling local environments can have a substantial impact on the quality of life for someone living with dementia, helping them to live well in their community for longer.

There are around 850,000 people living with dementia in the UK. This figure is projected to increase to 1.6 million people by 2040. People living with dementia may experience the built environment differently to other people. Evidence has shown that good quality housing and well-planned, enabling local environments can have a substantial impact on the quality of life for someone living with dementia, helping them to live well in their community for longer.

The RTPI originally published this advice in 2017 and it has been influential in the UK and internationally. We are pleased to hear about examples of how the advice has encouraged planners to integrate planning for dementia friendly environments into their plans, advice and developments. This revised version includes some of these new examples of good practice, along with updated information, advice and practice.

This practice note gives advice on how town planning can work with other professionals to create better environments for people living with dementia. It summarises expert advice, outlines key planning policy, good practice and case studies from around the UK. The policy context applies to England, Scotland, Wales, Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland. However, the principles of good practice are applicable wherever you work in the world.

This advice has been endorsed by Alzheimer's Society and Public Health England.

Download the full report here or read below.

For more information contact [email protected]

Please note that The RTPI runs a CPD Masterclass on ‘Planning for Public Health and Wellbeing’ each year. Please find the upcoming dates of this masterclass in the CPD Training Calendar.

If you have any question relating to CPD training, please email: [email protected]

Dementia and town planning: Creating better environments for people living with dementia

Contents

- Introduction 3

- About dementia 4

- Impact of the built environment 8

- Home and dementia 12

- What does a place designed for people living with dementia look like? 18

- Legislation and policy 22

- Planning for dementia 26

- Tools and approaches to plan for people living with dementia 32

- Further information 36

1. Introduction

There are around 850,000 people living with dementia in the UK[1]. This figure is projected to increase to 1.6 million people by 2040. People living with dementia may experience the built environment differently to other people. Evidence has shown that good quality housing and well-planned, enabling local environments can have a substantial impact on the quality of life for someone living with dementia, helping them to live well in their community for longer. An over-riding principle of this advice is that if you get an area right for people with dementia, you can also get it right for older people, for young disabled people, for families with small children, and ultimately for everyone.

The RTPI originally published this advice in 2017 and it has been influential in the UK and internationally. We are pleased to hear about examples of how the advice has encouraged planners to integrate planning for dementia friendly environments into their plans, advice and developments. This revised version includes some of these new examples of good practice, along with updated information, advice and practice.

The Covid-19 pandemic has affected older people at a higher rate than other parts of society. The impact of local and national lockdowns has been an extremely difficult time for everyone and especially for people living with dementia, their families and carers. This advice attempts to reflect on the challenges they face, along with how the built environment can be adapted to improve their safety and support them to live independently in the future.

This practice note gives advice on how town planning can work with other professionals to create better environments for people living with dementia. It summarises expert advice, outlines key planning policy, good practice and case studies from around the UK. The policy context applies to England, Scotland, Wales, Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland. However, the principles of good practice are applicable wherever you work in the world.

The audience for this advice is primarily RTPI members, but it is also relevant to other built environment professionals, local politicians, charities and public health professionals.

2. About dementia

Before examining the impact of the built environment on the lives of people living with dementia and the role of town planners in improving the situation, it is important to understand the impact of dementia on the individual and society.

What is dementia?

Dementia is an umbrella term and is caused when diseases, such as Alzheimer’s, vascular dementia, frontotemporal dementia, and other conditions damage the brain. All types of dementia are progressive and each person will experience dementia in their own way. Dementia describes a set of symptoms that may include memory loss and difficulties with thinking, problem solving or language. These changes are often small to start with, but for someone with dementia they have become severe enough to affect daily life. A person living with dementia may also experience changes in their mood or behaviour. There are also sensory challenges, including vision, hearing, perception and balance, along with taste and smell that many people with dementia experience. The specific symptoms that someone experiences will depend on the parts of the brain that are damaged and the disease that is causing dementia.

Whilst dementia is most common in older people, some people experience young-onset dementia. Dementia can also exacerbate the effects of physical impairments and other health conditions. In older age groups, especially, it is common for people living with dementia to have more than one type.

Prevalence of dementia

There are around 850,000 older people living with dementia in the UK[2]. This equates to 748,000 people in England, 66,300 people in Scotland, 46,800 people in Wales, and 22,000 people in Northern Ireland. The Alzheimer Society of Ireland[3] reports that an estimated 55,000 people were living with dementia in Ireland in 2017. This is split between 127,000 people with mild dementia, 246,000 with moderate dementia and 511,000 with severe dementia. This gives an estimated prevalence rate amongst older people in the UK of around 7%.

Alzheimer’s Society predicts an 80% increase to around one million in 2024 and 1.6 million people living with the condition by 2040 (people aged 65 and over); at a prevalence rate of 8.8%[4] in the UK. There are over 42,000 people living in the UK with young-onset dementia[5]. In Ireland, the total number of people living with dementia is expected to be 113,000 in 2036.

The report from Alzheimer’s Society, “Projections of older people with dementia and costs of dementia care in the United Kingdom, 2019–2040”, includes details of the projected number of people aged 65 and over with dementia, alongside the projected total costs of dementia for each local authority in England, based on Office for National Statistics (ONS) population projections. 1 in 14 people over the age of 65 have dementia, rising to 1 in 6 over the age of 80.

Alzheimer’s Research UK, has developed an interactive map[6] to show the estimated number of people living with dementia at the parliamentary constituencies and Clinical Commissioning Groups’ level. The map shows that coastal constituencies in the south of England have the highest number of people living with dementia per head of population. Christchurch, in Dorset had the highest number of people living with dementia at 2,400 people, 2.8% of the population in 2015. Public Health England collates detailed datasets on dementia[7] that provide information that enables interrogation on trends, and variations across different parts of England.

The increase in the number of people living with dementia is largely due to the ageing population in the UK and Ireland. According to ONS population projections the number of older people aged 65–74 in the UK will increase by 20% between 2019 and 2040, and the number of older people aged 85 and over will increase by 114%. It is also worth noting that 65% of people living with dementia are women. There is also a greater prevalence of dementia among black and South Asian ethnic groups. These groups are more prone to risk factors such as cardiovascular disease, hypertension and diabetes, which increase the risk of dementia and contribute to increased prevalence.

Globally, the World Health Organisation estimates the number of people with dementia to be 50 million and recognises the disease as a public health priority[8].

There are behavioural changes that an individual can take to reduce their risk of developing dementia. These include drinking less alcohol, stopping smoking, maintaining a healthy weight, and being be physically and socially active. In line with this advice, health and care professionals are being encouraged by Public Health England to take a think prevention first to dementia care. The quality of the built environment can have an impact on how easily individuals can make these behavioural changes.

Financial cost of dementia

The total cost of care for people with dementia in the UK is £34.7billion per annum. This is set to rise by 172% to £94.1 billion in 2040. These costs are made up of healthcare costs (costs to the NHS), social care costs (costs of homecare and residential care), and costs of unpaid care (provided by family members). The largest proportion of this cost, 45%, is social care, at £15.7billion. This is during a period when social care costs are set to nearly triple to £45.4billion[9].

Families pay more than 60% of the total social care costs in England, £8.3billion a year, compared to £5.2billion paid by the Government. Families and friends provide unpaid care to a value of £13.9billion a year. This is projected to increase to £35.7billion by 2040.

The overall cost of dementia care in Ireland is €1.69 billion per annum. This consists of 48% of family care and 43% residential care. Formal health and social care services contributing to 9% of the total cost.

Public Health England reports on the levels of short stay emergency admissions as a proportion of all emergency admissions of people of with dementia aged over 65. These have continued to rise, from 30.8% in 2018, to 32.4% in 2019 for England[10].

Housing

The majority of people with dementia in the UK and Ireland live at home in the community. Only 39% of people with dementia aged over 65 live in care homes according to Alzheimer’s Research UK[11]. Of those who live in their own homes, 120,000 live alone and this is predicted to double to around 240,000 by 2039. In order to be able to live alone the appropriate practical and emotional support and housing choices are vital to enable people with dementia to live well and safely. A survey by Alzheimer’s Society in 2019 of people with dementia about their experiences of living in the community reveal that over half experience loneliness and isolation after being diagnosed[12].

Alzheimer’s Society believes people with dementia who want to remain in their own homes should be supported to do so for as long as possible. There are also financial benefits of helping people to do so. One year of high-quality care in the community costs £11,000 less than in a care home[13].

People with dementia may go into residential care homes earlier than they want to because their own homes are not designed to enable them to live independently and can be expensive to adapt to meet their needs. This is despite 85% of people saying they would choose to live at home for as long as possible if diagnosed with dementia[14]. Staying in familiar surroundings with the right support can help people living with dementia continue to lead an active and independent life for longer. However, only 7% of housing in England is accessible and 20% of homes occupied by older people in England fail the Government’s basic standard of decency[15]. Whilst these are broader definitions and do not specifically refer to people living with dementia, many people with the condition do live in inadequate housing, that can impact on their health. Similar rates exist across the rest of the UK and Ireland.

Covid-19 and dementia

The Covid-19 pandemic has had a disproportionate impact on older people. The ‘Disparities in the risk and outcomes of COVID-19’[16] report published by Public Health England states, ‘The largest disparity found was by age. Among people already diagnosed with Covid-19, people who were 80 or older were seventy times more likely to die than those under 40’. The picture for people living with dementia is also stark. Figures from the Office for National Statistics show that of the 46,687 deaths involving Covid-19 in England and Wales between March and May 12,856 (27.5%) had dementia[17]. There has also been an increase in the death rate of people with dementia who do not have Covid-19. People living with dementia, who are the biggest users of social care services and have unique challenges in terms of infection control and the damaging impact of social isolation[18].

The impact of the lockdown on changes to established routines, social contact and social care have had a profound impact on people living with dementia. People living with dementia and their carers have expressed fears over losing basic cognitive and communication skills due to social isolation during this time.

The first wave of the Covid-19 pandemic in the first half of 2020 is may not be the only time the UK and Ireland implements widespread lockdown measures to control a pandemic. Even as the lockdown measures were being relaxed in June 2020, localised lockdowns were being introduced. The RTPI campaign and accompanying research, ‘Plan The World We Need’[19] highlights the need for a sustainable, resilient and inclusive recovery for all parts of society, including older and disabled people, and the key role of town planning in delivering it.

3. Impact of the built environment

Many factors have an impact on how well someone with dementia is able to live with the condition. This includes medical care, access to services and the support of family and friends. The built and natural environment also has an important role to play in maintaining health, wellbeing and independence.

Social interaction

It is vital that people with dementia stay as active as they can, physically, mentally and socially. People with dementia need meaningful activities they enjoy, which can maintain their confidence. However, a survey by Alzheimer’s Society in 2013 found that 35% of people with dementia said they only go out once a week or less and 10% said once a month or less[20]. The most common local activities for people with dementia were identified as shopping (79%), socialising (72%), eating out (69%), and leisure activities (55%), such as going to the park, library or cinema. Many people feel constrained by dementia and are not confident to go out in their local area.

Keith Oliver, Alzheimer's Society ambassador[21]

Innovations in Dementia sought the views of people with dementia about the concept of dementia capable communities[22]. They found that the popular activities to keep in touch and involved in the local community were using local facilities like the shops, church, pub, and gym. Many people felt that walking provided them with an important connection to their community, as well as maintaining their physical health.

Respondents in the report were asked to imagine a community that is perfect for people with dementia. This response best describes the type of places that should be created.

Dementia Capable Communities report respondent[23]

Built environment

The local environment is a fundamental factor contributing to the quality of life of older people, it can either be enabling or disabling. Having access to amenities like local shops, doctors, post offices and banks within easy, safe and comfortable walking distances contributes to people with dementia being able to live independent and fulfilling lives for longer. It is also important to consider the significant role that consistency and familiarity plays in giving people confidence and helping them to feel safe. This can be as simple as the purpose of a building being obvious or having clear lines of sight through a development. A survey of people living with dementia found that 60% worry about getting lost, and this is more prevalent amongst people living in urban areas, especially when using public transport[24].

Careful consideration must be given to the design and location of housing for older people; whether this is mainstream or specialist housing. If it is located in community hubs within a 5-10 minute walk of local shops and services[25], this will help enable people living with dementia to live well and remain independent for longer. The location of extra-care housing also has implications for the resident’s family and carers. Edge of town development, badly served by public transport can cause issues for staff who are often low-paid and can work unsociable hours, as well as potentially making it more difficult for family and friends to visit. All the considerations that planners promote in well-planned places are particularly important for people living with dementia.

Interviewee in Alzheimer’s Society ‘Turning up the Volume’ report[26]

Value of greenspace

The link between green space and wellbeing is well established. Studies have shown that individuals experience less mental distress, less anxiety and depression, greater wellbeing and healthier cortisol profiles when living in urban areas with more greenspace compared with less[27]. For people living with dementia, engaging with greenspaces can positively influence eating and sleeping patterns, fitness and mobility, a sense of wellbeing and self-esteem[28]. Dementia professionals promote the inclusion of access to nature and greenspace as an important component of delivering a dementia friendly environment. It encourages people to be active, engaged in their surroundings, and provides opportunities for social interaction.

Peter Jones, 66, Carlisle, with vascular dementia[29]

A Natural England report, ‘Is it nice outside?[30]’ investigated the key benefits of engaging with the natural environment for people living with dementia; along with identifying barriers and potential changes to make the natural environment more accessible. It found that informal walking was the most commonly cited activity by people living with dementia, with wildlife watching another popular pastime. Places associated with water (inland, coast, natural, artificial) were the most popular places to visit for people with dementia along with city parks or public gardens. In the report, several people with dementia talked about the role their local park played in providing them with somewhere to go, and as somewhere to enjoy watching other people taking part in activities.

Participant - Stockwell[31]

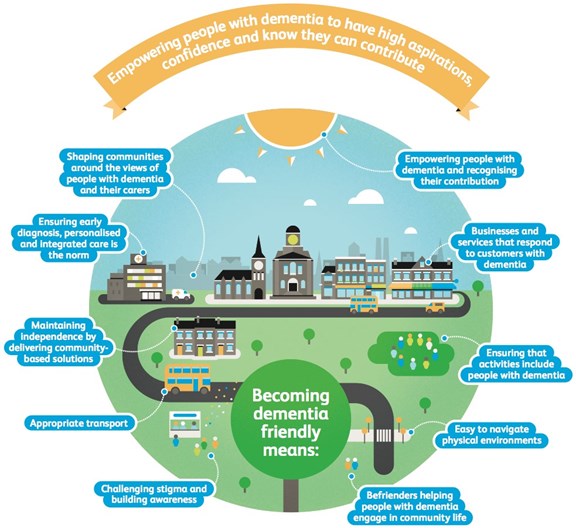

Dementia Friendly Communities

There are around 428 Dementia Friendly Communities in England and Wales in 2020[32]. To engage in this process communities commit to delivering change that enables public recognition of their work towards becoming dementia friendly. Communities need to demonstrate that the right local structure is in place, focusing plans on a number of locally identified areas of need and developing a strong voice for people with dementia. The characteristics of a dementia friendly community have been identified and include; shaping communities around the views of people with dementia and their carers, appropriate transport, and easy to navigate physical environments.

The scheme has demonstrated that small changes can make a big difference. ‘BSI PAS1365: Code of practice for the recognition of dementia-friendly communities in England (2015)’[33] provides detailed guidance and structure around what dementia friendly looks like. There is a role for town planners in creating Dementia Friendly Communities.

Case study: Integrated dementia friendly town planning - Plymouth City Council

The Strategic Planning and Infrastructure Department at Plymouth City Council works together with the Dementia Friendly City Coordinator. The award winning Plymouth Plan contains the ambition to become a dementia friendly city. It is outlined in policy HEA1 - Addressing health inequalities, that states, ‘Promoting mental wellbeing, resilience and improved quality of life through improving the range of and access to mental health and early intervention services, integrating physical and mental health care and becoming a Dementia Friendly City[34].

In 2020 there are estimated to be 3,600 over-65s living with dementia in Plymouth and this is predicted to increase to 4,770 (a growth of 35.8%) by 2030. Plymouth became dementia friendly because researchers at Plymouth University found that many people with dementia were lonely and isolated in the local community. They found significant rates of depression for the individual and their carer, all of which may have contributed to early moves into residential care. The aim of Plymouth’s Dementia Friendly City is for, “people to feel they have a choice and control over the decisions about their life, to feel a valued part of the community and live well with dementia”[35].

Plymouth and South West Devon Joint Local Plan follows on from the Plymouth Plan and was adopted in 2019. Although it does not include direct references to dementia, it does contain policies that support a dementia friendly city. These include:

DEV1 - Protecting health and amenity

‘2. Ensuring that developments and public spaces are designed to be accessible to all people, including people with disabilities or for whose mobility is impaired by other circumstances.’

SPT2 - Sustainable linked neighbourhoods and sustainable rural communities

- Have reasonable access to a vibrant mixed use centre, which meets daily community needs for local services such as neighbourhood shops, health and wellbeing services and community facilities, and includes where appropriate dual uses of facilities in community hubs; and,

- Have services and facilities that promote equality and inclusion and that provide for all sectors of the local population.

The view of Plymouth’s Strategic Planning and Infrastructure Department’s is, “the key for successful projects is to ensure that the dementia community is properly consulted and involved to inform the measures that will be implemented.”

4. Home and dementia

The design of housing suitable for people living with dementia is extremely important. Careful attention to design features must be taken, whether this is a family home, extra care housing, residential care or nursing care. Often small changes can be enough to help someone living with dementia to be more independent by providing an environment that is clearly defined, easy to navigate, and feels safe. Whilst the internal layout of buildings is usually beyond the scope of the role of planners, it is still valuable to be aware of the key principles of good design. These include:

Safety– avoid trip hazards; or changes in depth; provide contrasting handrails and good lighting;

Safety– avoid trip hazards; or changes in depth; provide contrasting handrails and good lighting;

Visual clues – clear signage, sightlines and routes around the building;

Visual clues – clear signage, sightlines and routes around the building;

Clearly defined rooms – activities that take place in each room can be easily understood;

Clearly defined rooms – activities that take place in each room can be easily understood;

Interior design – avoid reflective surfaces and confusing patterns. Use age and culturally appropriate designs;

Interior design – avoid reflective surfaces and confusing patterns. Use age and culturally appropriate designs;

Noise – reduce noise through location of activities and soundproofing. Provide quiet areas as people with dementia can be hyper-sensitive to noise or have hearing loss;

Noise – reduce noise through location of activities and soundproofing. Provide quiet areas as people with dementia can be hyper-sensitive to noise or have hearing loss;

Natural light or stronger artificial light – many people with dementia have visual and perceptional difficulties, sight loss impairment or problems interpreting what they see;

Natural light or stronger artificial light – many people with dementia have visual and perceptional difficulties, sight loss impairment or problems interpreting what they see;

Images credit: All of these interior images are of the Building Research Establishment (BRE) Dementia-friendly demonstration home. See case study below for more information.

Outside space – access to safe outside space, with good views from inside the building as daily exposure to daylight improves health and circadian rhythm.

Outside space – access to safe outside space, with good views from inside the building as daily exposure to daylight improves health and circadian rhythm.

Image credit: The Orders of St John Care Trust

These features of good design reflect the Housing our Ageing Population Panel for Innovation (HAPPI)[36] principles, based on ten key design criteria. Many are recognisable from good design generally, but they have particular relevance to older peoples' housing, which should be able to adapt over time to meet changing needs. Dementia friendly health and social care environments[37] also gives detailed design principles accompanied by a clear rationale for dementia friendly environments in healthcare buildings.

The RTPI is a stakeholder for the Dementia Friendly Housing Charter[38] that aims to promote how housing, its design and supporting services can help improve and maintain the wellbeing of people affected by dementia. Our stakeholder endorsement made the link between housing quality and the wider local environment. It says, “Good quality housing, located in the right places, along with well-planned, enabling local environments can have a substantial impact on the quality of life of someone living with dementia, helping them to live well for longer.”

Case study: Housing design - BRE dementia house

The Building Research Establishment (BRE) have created a dementia-friendly demonstration home[39] at their Innovation Park in Watford to showcase evidence-based design, adaptation and support solutions which allow people to age well at home. A 100sqm Victorian house has been adapted to cater for different types and stages of dementia. The design of the house aims to assist people living with dementia to live independently by addressing their day-to-day needs. The building has been designed around the needs of two specific personas, Chris and Sally. It shows how the features of the building have been adapted to support them as they age well at home. Short films that detail how dementia affects Chris and Sally on a good, average and bad day are shown in the prototype, which supports communication of the key features of the home. The demonstration home is based on ‘Design for Dementia’[40], a research partnership into living better at home with dementia. An important feature of the house is that it looks like a home, even though it has been designed specifically for the needs of someone living with dementia, with the specialist equipment required as the disease progresses.

Case study: International best practice dementia care home - Hogeweyk, Netherlands

Hogeweyk[41] in the Netherlands was opened in 2009. It is a specially designed village with 23 houses for 152 people living with dementia that is internationally recognised as best practice in dementia care. The residents all need nursing home facilities and live in houses differentiated by lifestyle. Hogeweyk offers seven different lifestyles: Goois, homey, Christian, artisan, Indonesian and cultural. The residents manage their own households, together with a stable team of staff members. The village has streets, squares, gardens and a park where the residents move around independently, but within a safe environment. Like any other village, Hogeweyk offers a selection of facilities, a restaurant, supermarket and theatre that Hogeweyk residents and people from the surrounding area can use. Key principles for the way that the village is designed and run is choice, normalcy, responding to individual needs and opportunity for social interaction.

Hogeweyk[41] in the Netherlands was opened in 2009. It is a specially designed village with 23 houses for 152 people living with dementia that is internationally recognised as best practice in dementia care. The residents all need nursing home facilities and live in houses differentiated by lifestyle. Hogeweyk offers seven different lifestyles: Goois, homey, Christian, artisan, Indonesian and cultural. The residents manage their own households, together with a stable team of staff members. The village has streets, squares, gardens and a park where the residents move around independently, but within a safe environment. Like any other village, Hogeweyk offers a selection of facilities, a restaurant, supermarket and theatre that Hogeweyk residents and people from the surrounding area can use. Key principles for the way that the village is designed and run is choice, normalcy, responding to individual needs and opportunity for social interaction.

Case study: Community centred extra care housing - Hull

The location and setting within the local community of extra care housing can be extremely important for how successful it is at enabling people to live well with dementia. According to Hull City Council, the prevalence of dementia in Hull is predicted to increase by 40% to 2025, and 156% by 2051. However, with only 40 extra care units in the city, and the Joint Housing Needs Survey identifying that over the 2016-32 period a need for 78 specialist housing for older people per year, representing around 14% of housing need in Hull it was seen as a priority to address future needs.

The location and setting within the local community of extra care housing can be extremely important for how successful it is at enabling people to live well with dementia. According to Hull City Council, the prevalence of dementia in Hull is predicted to increase by 40% to 2025, and 156% by 2051. However, with only 40 extra care units in the city, and the Joint Housing Needs Survey identifying that over the 2016-32 period a need for 78 specialist housing for older people per year, representing around 14% of housing need in Hull it was seen as a priority to address future needs.

The process of developing the 316 affordable rent, extra care housing units began with the site appraisal for a number of sites to identify suitable locations. Sites were assessed against local plan policy, flood risk zone (95% of Hull is high flood risk and the vulnerability of the residents is similarly high) transport accessibility and compatibility with neighbouring uses. The development is across three sites. This means that prospective tenants have access to a relatively local housing option, limiting disruption to established relationships and lifestyles as little as possible.

A service level agreement between the planning department and Adult Social Care assured 20 hours per week of dedicated senior planning officer time as a member of the private finance initiative project team. Alongside this, the Hull City Council Planning Manager sat on the project board from inception to completion. This gave the opportunity for town planning input at each stage of the process, providing advice on design quality, timeframe, political sensitivities and community engagement. Learning from this project has been applied to the design of other residential schemes in the city.

A service level agreement between the planning department and Adult Social Care assured 20 hours per week of dedicated senior planning officer time as a member of the private finance initiative project team. Alongside this, the Hull City Council Planning Manager sat on the project board from inception to completion. This gave the opportunity for town planning input at each stage of the process, providing advice on design quality, timeframe, political sensitivities and community engagement. Learning from this project has been applied to the design of other residential schemes in the city.

Redwood Glades is one part of the project. It is a dementia friendly, extra care housing development for affordable rent for adults aged 18+ with general needs, dementia, physical, mental and learning disabilities. It allows general public access to many of the on-site facilities such as the garden, restaurant/café, communal lounge, and hair salon, beauty therapists, and chiropodists. The open facing nature of the development encourages the wider neighbourhood to engage and interact with the centre and their inhabitants. This, along with the site’s proximity to local shops and services, and public transport, and developing intergenerational relationships within the facilities helps residents to avoid feeling isolated. There is anecdotal evidence of direct health benefits, with emergency staff reporting a decrease in admissions since the developments have opened. The project was shortlisted for the RTPI Awards for Planning Excellence in 2018

Images credit: Tony McAteer/Gleeds

Case study: Adapting to Covid-19 - Connaught Court, York

This 90 bed residential, nursing and dementia care home has been innovative within the Government guidelines to provide residents with contact with family and friends. A partitioned visiting space has been created for family members to visit residents on an appointment only basis. It has an airtight, glass screen to ensure the safety of residents, their families, and the home’s staff. Visitors enter and exit the room from outside the home to minimise the risk of infection, whilst residents access the room from a different door inside the home. The pod has an intercom system to allow residents and their visitors to speak with each other easily. Both sides of the pod are deep cleaned between each visit[42]. This simple adaptation is something that could be included within the design of new care homes to future proof them to allow visits to residents to continue throughout all seasons during possible future infection outbreaks.

This 90 bed residential, nursing and dementia care home has been innovative within the Government guidelines to provide residents with contact with family and friends. A partitioned visiting space has been created for family members to visit residents on an appointment only basis. It has an airtight, glass screen to ensure the safety of residents, their families, and the home’s staff. Visitors enter and exit the room from outside the home to minimise the risk of infection, whilst residents access the room from a different door inside the home. The pod has an intercom system to allow residents and their visitors to speak with each other easily. Both sides of the pod are deep cleaned between each visit[42]. This simple adaptation is something that could be included within the design of new care homes to future proof them to allow visits to residents to continue throughout all seasons during possible future infection outbreaks.

Image credit: York Press

5. What does a place designed for people living with dementia look like?

As outlined in chapter 3 the built and natural environment has an important role to play in maintaining the wellbeing and independence of people living with dementia, enabling them to live well for longer. This can be outlined in some simple design principles that can be applied to a large number of settings - urban or rural, new development or existing settlements. These principles are based on ‘Designing dementia-friendly outdoor environments’ by Oxford Brookes University[43].

Familiar - functions of places and buildings are obvious, any changes are small scale and incremental;

Familiar - functions of places and buildings are obvious, any changes are small scale and incremental;

Legible - a hierarchy of street types, which are short and fairly narrow. Clear signs at decision points;

Legible - a hierarchy of street types, which are short and fairly narrow. Clear signs at decision points;

Distinctive - a variety of landmarks, with architectural features in a variety of styles and materials to distinguish them from one another. There is a variety of practical features, e.g. trees and street furniture; but these are not cluttered;

Distinctive - a variety of landmarks, with architectural features in a variety of styles and materials to distinguish them from one another. There is a variety of practical features, e.g. trees and street furniture; but these are not cluttered;

Accessible - land uses are mixed with shops and services within a 5-10 minute walk from housing. Entrances to places are obvious and easy to use and conform to disabled access regulations;

Accessible - land uses are mixed with shops and services within a 5-10 minute walk from housing. Entrances to places are obvious and easy to use and conform to disabled access regulations;

Comfortable - open space is well-defined, with toilets, seating, shelter and good lighting. Background and traffic noise should be minimised through planting and fencing. Street clutter is minimal to aid walking and focus attention;

Comfortable - open space is well-defined, with toilets, seating, shelter and good lighting. Background and traffic noise should be minimised through planting and fencing. Street clutter is minimal to aid walking and focus attention;

Safe - footpaths are wide, flat and non-slip, development is orientated to avoid creating dark shadows or bright glare, use of shared spaces is avoided.

Safe - footpaths are wide, flat and non-slip, development is orientated to avoid creating dark shadows or bright glare, use of shared spaces is avoided.

Case study: Dementia-friendly garden – Kirriemuir, Angus

Angus Council worked in partnership with Historic Environment Scotland on a Conservation Area Regeneration Scheme to enhance the appearance of Kirriemuir Conservation Area. A conservation area appraisal and management plan was produced to analyse the area's special character and a programme of works was undertaken to improve the built fabric and public realm. The regeneration scheme ran in parallel with work being undertaken by the Dementia Friendly Kirriemuir Project, funded by the Life Changes Trust. The Council gave planning permission for a change of use and approved the lease of derelict land in Kirriemuir to develop a dementia friendly garden with a rent of £1.00 per year. The garden is a safe, friendly, outdoor space that people living with dementia, their carers and family, as well as members of the local community can enjoy and help to maintain. The project has also reduced clutter within the public realm and provided a sympathetic approach to meeting the needs of both the historic built environment and those living in the area, particularly people living with dementia. This is a successful small rural project where partners have worked collaboratively to achieve outcomes that are beneficial to the whole community.

Angus Council worked in partnership with Historic Environment Scotland on a Conservation Area Regeneration Scheme to enhance the appearance of Kirriemuir Conservation Area. A conservation area appraisal and management plan was produced to analyse the area's special character and a programme of works was undertaken to improve the built fabric and public realm. The regeneration scheme ran in parallel with work being undertaken by the Dementia Friendly Kirriemuir Project, funded by the Life Changes Trust. The Council gave planning permission for a change of use and approved the lease of derelict land in Kirriemuir to develop a dementia friendly garden with a rent of £1.00 per year. The garden is a safe, friendly, outdoor space that people living with dementia, their carers and family, as well as members of the local community can enjoy and help to maintain. The project has also reduced clutter within the public realm and provided a sympathetic approach to meeting the needs of both the historic built environment and those living in the area, particularly people living with dementia. This is a successful small rural project where partners have worked collaboratively to achieve outcomes that are beneficial to the whole community.

Image credit: Kirrie Connections

Covid-19 and town planning

The impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic could be present for many years to come and future pandemics may be a possibility. It is too early to make predictions about the extent to which social distancing measures will remain in place and the changes this could mean for people living with dementia in how they move around their local area and continue to access to services and greenspace with any certainty. However, as the RTPI report ‘Plan The World We Need[44]’ outlines, there is likely to be a greater focus on local neighbourhoods to deliver the everyday services that are vital for people living with dementia to access close to home.

Adaptations, even if temporary need to be accessible for all and comply with relevant equality and access legislation. The changes being put in place for a longer-term shift to active travel and social distancing must meet the needs of all parts of society, including people with dementia.

Street spaces post-lockdown are anticipated to see an increase in cycles and micro-mobility vehicles as people change the way they travel. This may create problems for people living with dementia and vulnerable pedestrians. Clarity on shared areas of the streetscapes can help prevent potential injuries to pedestrians and encourage more people to walk if they are able to.

Case study: Safe social spaces - UK Meeting Centres Support Programme

The UK Meeting Centres Support Programme is based on a successful model from the Netherlands. The aim of the meeting centres is to provide a safe social space for people living with dementia and their carers to meet. All activities are designed to help people adapt to the challenges that living with dementia can bring. The approach fits within the social model of support. There is good evidence that people attending meeting centres experience better self-esteem, greater feelings of happiness and sense of belonging than those who do not attend.

Each meeting centre is community led. Therefore, the way the buildings look and function are very different. They are located in village halls and other local community buildings not within clinical settings, as these can promote feelings of anxiety for people living with dementia. Features of the buildings should encompass dementia friendly design – light, welcoming and well located within the local area, with links to other services. If planners have an understanding of the value of dementia meeting centres they can identify potential locations and design requirements in wider development and redevelopment schemes. There are currently four demonstrator sites in the UK, and a total of 15 centres across the country. The demonstrator sites work directly with the Association for Dementia Studies at the University of Worcester[45] to provide training and to share best practices who have a full range of training and resources available.

6. Legislation and policy

Promotion of healthy places is woven into UK planning policy systems. With the UK and Ireland’s ageing population there is an increasing focus on housing for older people. However, the references to dementia specifically are more limited.

Equalities legislation

Age, disability and gender are three of the nine protected characteristics covered by the Equality Act 2010 in England, Wales and Scotland. The Act is supported by the Public Sector Equality Duty[46], which requires public authorities to promote equality amongst people from protected groups by: removing or minimising disadvantages; taking steps to meet their needs where they are different from the needs of other people; and encouraging participation in public life or in other activities where their participation is disproportionately low. The aim of the Duty is to integrate consideration of equality and good relations into the day-to-day business of public authorities. BAME people and women are more likely to develop dementia, and these equality issues, also need to be taken into account. The Public Sector Equality Duty means public authorities and their delivery partners must think about whether they should take action to meet these needs or reduce the inequalities. This should be through an Equality or Diversity Impact Assessment.

The All-Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) on dementia and disability[47] found in 2019 that even though dementia is defined in legislation as a disability, people with the condition are still not given the protection that they should be. It makes a series of recommendations, including on transport, housing and community life. In Northern Ireland there are similar legal protections and responsibilities for public authorities[48]. The Irish Human Rights and Equality Commission enforces the Public Sector Equality and Human Rights Duty under the Irish Human Rights and Equality Act 2014[49]. Given the complex needs of people living with dementia the provision of housing, planning and other services need to be carefully considered within the context of equality legislation.

England

The National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF)[50] states that, ‘planning policies and decisions should aim to achieve healthy, inclusive and safe places which ….. enable and support healthy lifestyles, especially where this would address identified local health and well-being needs’ (Section 8). It also states in Section 5, Delivering a sufficient supply of homes that, ‘it is important that ……. the needs of groups with specific housing requirements are addressed‘.

The accompanying National Planning Policy Guidance on housing for older and disabled people was updated in 2019 and provides guidance on planning for people with dementia in the wider context of an ageing population in terms of calculating need, provision of specialist housing, inclusivity and accessibility. The guidance has been strengthened with the addition of a paragraph that specifically addresses the needs of people living with dementia. It outlines the characteristics of a dementia friendly community and states, “There should be a range of housing options and tenures available to people with dementia, including mainstream and specialist housing. Innovative and diverse housing models should be considered where appropriate”[51].

Health and Wellbeing Boards plan how to meet the health needs of the local population. Each Board is responsible for producing a health and wellbeing strategy, which is underpinned by a joint strategic needs assessment. This will be a key strategy for a local planning authority to take into account to improve health and wellbeing.

Scotland

Planning (Scotland) Act 2019, states that in the National Planning Framework, the outcomes include meeting the housing needs including, in particular, the housing needs for older people and disabled people and improving the health and wellbeing of people living in Scotland[52].

The current National Planning Framework 3 (2014)[53] remains in place until NPF4 is adopted in 2021. One of the main changes will be that NPF4 will need to align with the outcomes in the National Performance Framework, which includes, ‘live in communities that are inclusive, empowered, resilient and safe’. With the specific vision for older people of, ‘Our older people are happy and fulfilled and Scotland is seen as the best place in the world to grow older. We are careful to ensure no one is isolated, lonely or lives in poverty or poor housing. We respect the desire to live independently and provide the necessary support to do so where possible’[54].

The Scotland National dementia strategy: 2017-2020[55] does not include a role for town planning in creating the neighbourhoods where people with dementia can live well.

Wales

Planning Policy Wales 10[56] has a good focus on accessibility. It states that ‘good design is inclusive design’. Whilst there is no specific mention of dementia it does say that development proposals must address the issues of inclusivity and accessibility for all. This includes making provision to meet the needs of people with sensory, memory, learning and mobility impairments, older people and people with young children.

In terms of housing, planning authorities should plan for a mix of market and affordable housing types, including meeting the housing requirements of older people and people with disabilities. Planning authorities should promote sustainable residential mixed tenure communities with ‘barrier free’ housing, for example built to Lifetime Homes standards[57] to enable people to live independently and safely in their own homes for longer.

Technical Advice Note 12 – Design[58] encourages a culture of inclusion in urban design. Where inclusive design creates barrier free environments. Importantly this is an implicit departure from a “special needs” approach to impairment which relies on adaptations to making places open for everyone to us. In every area of development, earlier and greater attention should be given to the needs of all sectors of society, including older people, children and disabled people. This principle applies to the design of the public realm, to public transport infrastructure and to the location, design and layout of public leisure facilities as well as the design of individual buildings. It goes on to say ‘designing for all means that consideration should include the needs of all, including people with mobility impairments, people with sensory impairments and people with learning difficulties’.

Planning policy in Wales is built on the strong foundations of the Well-being of Future Generations (Wales) Act 2015[59] through the seven interconnected, sustainable, well-being goals, including a healthier Wales and a Wales of cohesive communities. The Act requires public bodies to make sure that they take account of the impact they could have on people living in Wales in the future, including older people and people with disabilities. Local well-being plans[60] set out the Public Services Board’s priorities and actions to improve the economic, social, cultural and environmental well-being of each area in Wales. The plans are not a planning document, but could provide useful information for planning teams.

There is a Dementia Action Plan for Wales 2018-2022[61]. It does not include a role for town planning in creating the neighbourhoods where people with dementia can live well.

Northern Ireland

Improving health and wellbeing is one of the five core planning principles of the Strategic Planning Policy Statement for Northern Ireland[62]. It calls for local authorities to ‘contribute positively to health and well-being through safeguarding and facilitating quality open space, sport and outdoor recreation; providing for safe and secure age-friendly environments; and supporting the delivery of homes to meet the full range of housing needs, contributing to balanced communities’. It also ‘encourages planning authorities to engage with relevant bodies and agencies with health remits in order to understand and take account of health issues and the needs of local communities where appropriate’.

One of the stated aims of the Regional Development Strategy 2035[63] is to, “promote development which improves the health and well-being of communities, however there is little reference to health in the rest of the document.

Ireland

Project Ireland 2040: National Planning Framework[64] was published 2018. It takes a whole system approach to addressing health and wellbeing. The Framework does not directly refer to dementia, but does acknowledge that a significant proportion of the population will experience disability at some stage in their lives, particularly as the population ages. Government policy supports older people to live with dignity and independence in their own homes and communities for as long as possible, requiring appropriate housing choices and a built environment that is attractive, accessible and safe. This reinforces the need for ‘well-designed lifetime adaptable infill and brownfield development close to existing services and facilities, supported by universal design and improved urban amenities, including public spaces and parks as well as direct and accessible walking routes’.

National Policy Objective 30

Local planning, housing, transport/ accessibility and leisure policies will be developed with a focus on meeting the needs and opportunities of an ageing population along with the inclusion of specific projections, supported by clear proposals in respect of ageing communities as part of the core strategy of city and county development plans.

Age Friendly Ireland[65] is identified as being able to provide the local leadership and guidance to meet the needs of an ageing population and is embedded within the local government system.

7. Planning for dementia

In order to effectively create places that work well for people living with dementia and how the local area and individual building can be designed adapted for them, dementia needs to be considered at all stages of the planning system. Waiting until the location or even design stages of individual buildings and places risks a piecemeal approach that ultimately creates further barriers to independence and increased costs.

Town planners should utilise the expertise of specialist organisations and accessibility consultants with experience of designing for, and consulting with, people living with dementia in order to ensure plans and developments truly meet their needs. By monitoring the level of dementia friendly development local authorities can ensure that there is sufficient provision to meet local needs and begin to identify gaps. Locally based dementia groups have valuable knowledge that can assist in this process.

With the use of a series of case studies, this section will highlight how consideration of dementia friendly environments at each stage in the planning process is the right approach. It includes:

- Including dementia at the scoping stage,

- Appropriate local plan policies,

- Integrated health guidance,

- Dementia friendly urban design guidance,

- Neighbourhood plan priorities,

- Positive pre-application discussions.

Case study: Including dementia at the scoping stage - South Ribble Borough Council

When South Ribble Borough Council began to review the Central Lancashire Local Plan[66] (which also covers Preston and Chorley), they appointed consultants from the University of Stirling to consult with people living with dementia to identify what a dementia friendly local plan would look like. Feedback from this process was used for the Issues and Options Consultation that closed in February 2020. The aim is to ensure that dementia is considered at all stages of the consultation process. These initial discussions will be revisited with the consultant and the borough’s Living Well Feedback Panel to gain further insight. The Panel has also been involved in giving feedback on individual projects including the design of a dementia garden and renovations of the civic offices. One of the main messages to come out of the discussions so far has been the need for clear readable signage. A simple, cost effective change that can make a big difference to how people living with dementia can move safely and confidently around the area.

Supporting people with dementia is a priority across the whole of South Ribble Borough Council. The initial impetus came from elected members. This has meant that a broad range of people within the council have been receptive to new initiatives. The council works closely with other partners through the South Ribble Dementia Action Alliance, which was key in developing the Living Well Feedback Panel and many other dementia friendly initiatives. South Ribble Borough Council describe the progress as, “We’ve started the journey but still have a very long way to go”.

Case study: Appropriate local plan policies - Watford Borough Council

Watford Borough Council prepared the first draft of their local plan[67] that outlines the vision for the borough up to 2036 in 2019. The plan will be adopted in May 2021. One of the biggest challenges identified in the plan is providing new housing for Watford’s growing population. The planning department has included clear and strong dementia policies. This is because by 2036, the number of people living with dementia is expected to increase to 2.2% of the population. The draft plan sets out the principles that should be designed into new residential developments to support people with dementia.

The policies in Watford’s draft plan are specific and measureable within the context of:

Policy H4.5 Accessible and Adaptable Homes,

‘To provide homes for elderly people and those with disabilities and dementia, the following will be required for proposals of ten or more dwellings’ and specifically:

Developers will be required to demonstrate how they have included dementia friendly principles of design as part of the proposal. 4% of new homes should be designed with dementia friendly principles in mind. This is in addition to the requirements in part (1) above.

Case study: Neighbourhood plan priorities – Cullompton Town Council, Devon

The Cullompton Neighbourhood Plan 2019-2033[68] passed the examination stage in late 2019 and a local referendum will follow. The aims and objectives for community wellbeing in the plan include to, ‘continue to improve community resilience’. The plan includes;

Policy WL08 Dementia Friendly Town

Proposals that contribute towards making Cullompton more dementia-friendly and an accessible town to disabled people are supported.

Development proposals will be expected to show how they incorporate the principles of dementia-friendly and fully accessible environments by reference to the Cullompton Dementia Strategy and other relevant Town Council strategies.

The Dementia Strategy will include a checklist that will be used to assess whether a development proposal will achieve a dementia-friendly outdoor environment. The Mid Devon local plan does not include a policy on dementia-friendly communities, but the local authority agrees that the policy conforms to Local Plan Review strategic policies.

The approach taken in Cullompton has strong support in the local community, with 98% of respondents to the consultation survey in 2016 in support of the proposed plan.

Case study: Integrated health guidance – Worcestershire County Council

The Strategic Planning team and Directorate of Public Health at Worcestershire County Council and representatives from the planning teams from the three South Worcestershire Councils (Malvern Hills, Wychavon and Worcester City) published a Planning for Health Supplementary Planning Document (SPD)[69] in 2018. The SPD provides guidance on creating healthier developments and gives an interpretation of the South Worcestershire Development Plan (2016) from a public health perspective. The SPD addresses nine health and wellbeing principles including, ‘age-friendly environments for the elderly and those living with dementia’.

The SPD is one part of a long-term commitment to forging a closer link between planning and public health that began in 2012 with the opportunities offered by the introduction of Health and Wellbeing Boards. Other activities include the secondment of a town planner to the Public Health Directorate for two years. With the result that both parties have increased their understanding of the others role, and continue to work together positively to secure health promoting environments.

The SPD has fed back into the review of the South Worcestershire Development Plan with the inclusion of a new strategic health and wellbeing policy. The county planners have also worked with Wyre Forest District Council on drafting a health and wellbeing policy for their Local Plan Pre-Submission Publication document. The plan is supported with further guidance in the SPD.

This integrated approach has been extended to neighbourhood planning. Following advice from the planning team the Alvechurch Neighbourhood Plan[70] includes a robust and detailed health and wellbeing policy with a specific reference to dementia.

Policy LHW1: Healthy environments and health care facilities

Development will be supported that contribute to improving health and wellbeing within the Neighbourhood Area including the provision of age and dementia friendly outdoor environments through:

- Providing a healthy living environment through good design and inclusion of green spaces ……

The first Planning for Health in Worcestershire Research paper published in 2015 informed all subsequent work in this area. Worcestershire County Council are now working in partnership with the district councils on a second paper focusing on ageing well in Worcestershire. It will address issues including dementia and ageing well with the aim to inform policy and decision-making. Publication is anticipated during Winter 2020/21.

Worcestershire demonstrates how a long-term, integrated approach has placed dementia friendly planning within a robust and innovative planning for health agenda across the whole county.

Case study: Dementia friendly urban design guidance – London Borough of Sutton

The London Borough of Sutton adopted the Sutton Town Centre Public Realm Design Guide[71] in January 2020. The guide sets out projects and guidelines to improve the street scene over a 15-year period. The guide is formed around 12 guiding principles, including, ‘Making Sutton an Age Friendly Town Centre’ and more specifically, ‘Making a Dementia Friendly Town Centre’. The guide outlines the principles of dementia friendly design contained in chapter 5 of this advice. At the start of the process, a street audit was conducted. It found poor disabled access, excessive hard landscaping, excessive street clutter and sparse public seating.

The London Borough of Sutton adopted the Sutton Town Centre Public Realm Design Guide[71] in January 2020. The guide sets out projects and guidelines to improve the street scene over a 15-year period. The guide is formed around 12 guiding principles, including, ‘Making Sutton an Age Friendly Town Centre’ and more specifically, ‘Making a Dementia Friendly Town Centre’. The guide outlines the principles of dementia friendly design contained in chapter 5 of this advice. At the start of the process, a street audit was conducted. It found poor disabled access, excessive hard landscaping, excessive street clutter and sparse public seating.

The focus on public realm was prompted by the anticipated level of change in Sutton town centre over the next 10-15 years because of the 41 redevelopment sites identified in the 2018 local plan, introduction of the Sutton Link tram and release of Transport for London funds for walking and cycling improvements, alongside potential heritage funding. The local authority were concerned that the changes to pavements and streets could lead to a ‘patchwork quilt’ effect, which would not enhance the centre. It was considered important to have a project ready guide for when funds are released.

The guide includes plans for 12 site-specific projects where the public realm could be improved to meet the guiding principles. Each project identifies the area, lists the interventions to make. There are also town centre-wide projects. This approach to dementia friendly design is valuable because it is fully integrated into wider, long-term policy and in advance of funding opportunities and upcoming developments for a wide town centre area. It is being used to inform the design of Sutton Park House, a major redevelopment project in the town centre. The document has also informed the introduction of Covid-19 social distancing measures.

Case study: Positive pre-application discussions - Teignbridge District Council

Teignbridge District Council in Devon approved a planning application for the Church Path Valley scheme in Exeter to build 240 homes in 2019. The application was the first reserved matters application for a wider site allocated in the Teignbridge Local Plan 2013 – 2033[72] as policy SWE1 – South West Exeter Urban Extension for up to 2,500 homes. The location of the site means that it has good access to existing amenities. 30% of the population of the district is aged over 60 and this is set to rise further. Teignbridge District Council is aware that they need to cater for the needs of this age group.

Teignbridge District Council in Devon approved a planning application for the Church Path Valley scheme in Exeter to build 240 homes in 2019. The application was the first reserved matters application for a wider site allocated in the Teignbridge Local Plan 2013 – 2033[72] as policy SWE1 – South West Exeter Urban Extension for up to 2,500 homes. The location of the site means that it has good access to existing amenities. 30% of the population of the district is aged over 60 and this is set to rise further. Teignbridge District Council is aware that they need to cater for the needs of this age group.

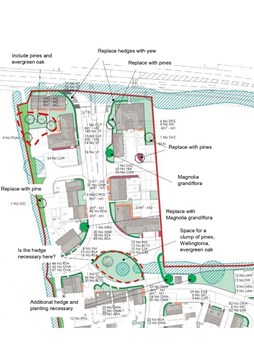

During pre-application discussions, the Senior Planning Officer made a number of urban design requests. This included a focus on designing for people living with dementia. The response from the developer, Cavanna has been very positive. The outcome has been a site designed with a positive approach to inclusive design and improved legibility. When residents enter the site, they can identify where they are at all times with clear boundaries, variety of materials and key buildings. There is a circular route to the housing layout to assist people living with dementia with wayfinding.

Also at the request of the Senior Planning Officer, a dementia garden has been included. It is located in the southern corner of the site, which is a peaceful area, away from the busier development entrance. The Officer provided general dementia friendly design principles that the developers have taken forward to create a sensory garden. The garden is located next to the proposed play area, which will encourage interaction between users of the garden, and the play area.

A public art officer has been appointed as part of the wider scheme. They have been given a brief to use legibility as a theme. With the public art designed to help with way finding, being placed at key decision points and each piece being individually distinctive to be used a landmark to help navigate.

As this is the first application as part of a large-scale development, it sets a precedent. Vistry Partnerships is the main developer for the rest of the site. An inclusive planning approach was raised at the very early stages of the pre-application discussion and again Vistry Partnerships have been supportive in accommodating the inclusive design approach to the site. Whilst this scheme is at an early on in the development process, and it will take some time to assess how it is implemented, so far this scheme demonstrates how the enthusiasm of an individual planner can add value and improve the inclusiveness of a scheme.

Image credit: Vistry Partnerships

8. Tools and approaches to plan for people living with dementia

There are a number of approaches and tools that planners can use to ensure their plans, decisions and places are dementia friendly. The right approach will depend on the circumstances, and whilst the RTPI does not recommend one approach over another, this chapter highlights some of the options available.

Partnership working

Planners need to develop effective partnerships with dementia care and service providers. These include social care; housing providers; health and wellbeing boards; NHS Trusts; and public health authorities. Health and wellbeing boards are responsible for encouraging integrated working on health and wellbeing issues, including the development of Joint Health and Wellbeing Strategies (JHWS), and Joint Strategic Needs Assessments (JSNA). The Planning Advisory Service in England recommends that local authorities identify a single point of contact for older people’s housing[73].

Health Impact Assessment

A health impact assessment (HIA) is a useful tool to use where there are expected to be significant health impacts of a development. When used proportionately HIAs can be explicit about identifying the health benefits and risks of a policy, plan or project. HIAs help to streamline the decision-making process based on shared goals of planners, public health professionals and the wider community.

Consultation tools

The Place Standard[74] is a tool developed by the Scottish Government, NHS Health Scotland and Architecture and Design Scotland. It is designed to help people talk about how they feel about their place in a methodical way. Local authorities are using it as a framework for consultation on development. People with dementia and their carers could use it to evaluate their local environment.

Walk the patch

This is a way of finding out how people with dementia at different stages experience their environment. It can involve accompanying someone with dementia on a short (45-minute) walk around their local area. As they do this, they explain their thought processes. Asking questions can act as a prompt. For example, what are you looking at? How did you choose between this way and that? Can you see that sign? Is it easy to find the entrance to the building? The Dementia Engagement and Empowerment Project (DEEP) have a guide and there is a network of active local groups. It is important to involve people with dementia, their families and carers in creating dementia friendly communities because,

“How can you know what ‘dementia friendly’ communities look and feel like without involving people with dementia (and carers)? We are the ones experiencing it.”[75]

Virtual environments

Stirling University’s Dementia Services Design Centre have a virtual environments tool. It allows users to visualise the key aspects of dementia friendly design for a care home and a hospital[76]. It demonstrates in a simple way the small-scale adjustments that can be made to make a place more dementia friendly.

Audit tools

Innovations in Dementia have published a checklist, “Is this outside public space dementia-inclusive?[77] It is for use by dementia groups, but would be a valuable consultation tool in terms of how to frame questions for discussion.

Alzheimer’s Society also have a Dementia Friendly Environment Checklist[78] that highlights simple steps that can be taken.

Consultation services

A number of dementia organisations provide a service to advise on and assess the suitability of an existing building or new development or plan for people living with dementia. The value of these services are that they can give detailed expert advice on a specific location. Consultants can be engaged at an early point in the process to ensure that dementia friendly design is fully integrated into the project.

Lifetime Homes Standard

Lifetime Homes[79] is comprised of 16 major standards that aim to provide homes, which are flexible and can cater for people with a wide range of disabilities. The 2015 Building Regulations M4 (2) ‘accessible, adaptable dwellings’[80] in England incorporates the majority of the Standard. Housing and disabled people[81] from the Equalities and Human Rights Commission and Habinteg is a toolkit for local authorities in England to planning for accessible homes.

Dementia Friendly Communities

The 428 Dementia Friendly Communities in England and Wales in 2020[82] [83] have a wealth of expertise and information about living with dementia. Most importantly, it is local. Engaging with these group means that planners can shape their communities around the views of people with dementia and their carers, to provide easy to navigate transport and physical environments.

Image credit: Alzheimer’s Society

Accreditation

The University of Stirling’s Dementia Services Design Centre offers a dementia design audit service[84] leading to accreditation. This is an independent audit to improve design for people with dementia. It provides a focus for cost-effective change. The award scheme also recognises those who have achieved success.

Case Study: Dementia friendly building accreditation - Great Sankey Neighbourhood Hub, Warrington

The Great Sankey Neighbourhood Hub[85] in Warrington involved an extensive addition, refurbishment, and partial change of use to an existing community sports complex. Additions included a public library, pharmacy, health consulting rooms, wellness suite, café, conference spaces, meeting rooms and offices. The University of Stirling’s awarded its internationally recognised dementia design Gold accreditation to the hub, the first public building in the world to receive the award.

The team from Dementia Services Development Centre praised the bold approach taken. The development has tackled several issues, including public mental and physical health, generational and cultural differences, and sustainability. A particular value of this project is that it provides integrated services for the whole community. By creating a fully dementia friendly public building means that people living with dementia are treated equally and as part of the local community.

9. Further information

Plan The World We Need: The contribution of planning to a sustainable, resilient and inclusive recovery - examines how planning can contribute to calls for a sustainable, resilient and inclusive recovery from the current health and economic crisis www.rtpi.org.uk/plantheworldweneed.

Alzheimer’s Society – UK dementia charity who campaign, fund research and support people living with dementia. Their services cover England, Wales and Northern Ireland. www.alzheimers.org.uk/.

Alzheimer Scotland – campaign, research and support www.alzscot.org/.

The Alzheimer Society of Ireland – provide dementia services, support and advocacy https://alzheimer.ie/.

Alzheimer’s Research UK – focus is on Alzheimer's disease research and health policy www.alzheimersresearchuk.org/.

Social Care Institute for Excellence (SCIE) - has a wealth of resources on supporting people with dementia www.scie.org.uk/dementia/.

Innovations in Dementia – charity that works with other organisations to provide dementia advice and advocacy www.innovationsindementia.org.uk/.

Wandering in Familiar Spaces – highlights the importance of inclusive urban design http://wanderinginfamiliarspaces.com/intro.html

Dementia UK – provides specialist dementia support with the Admiral Nurse service www.dementiauk.org/.

Dementia: applying All Our Health – guidance from Public Health England www.gov.uk/government/publications/dementia-applying-all-our-health/dementia-applying-all-our-health.

Public Health England – Government agency aims to protect and improve health and wellbeing www.gov.uk/government/organisations/public-health-england.

[1] www.alzheimers.org.uk/about-us/policy-and-influencing/dementia-scale-impact-numbers

[4] Report commissioned by Alzheimer’s Society from the Care Policy and Evaluation Centre at the London School of Economics and Political Science www.alzheimers.org.uk/about-us/policy-and-influencing/dementia-scale-impact-numbers

[5] www.alzheimers.org.uk/about-dementia/types-dementia/younger-people-with-dementia?gclid=CjwKCAjwltH3BRB6EiwAhj0IUAv97VW2K62Pqfp3E8aTAKEOcW-TkZeBpMORxLdGlyjXtjgrBYW6dBoCZ48QAvD_BwE&gclsrc=aw.ds

[6] www.dementiastatistics.org/statistics/dementia-maps

[7] https://fingertips.phe.org.uk/search/dementia#page/0/gid/1/pat/6/par/E12000004/ati/102/are/E06000015/cid/4/page-options/ovw-do-0

[8] www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia

[9] www.alzheimers.org.uk/about-us/policy-and-influencing/dementia-scale-impact-numbers

[10] www.gov.uk/government/publications/dementia-profile-april-2020-data-update/statistical-commentary-dementia-profile-april-2020-update

[11] www.dementiastatistics.org/statistics/care-services/

[12] www.alzheimers.org.uk/news/2019-05-15/lonely-future-120000-people-dementia-living-alone-set-double-next-20-years

[13] ibid

[14] www.alzheimers.org.uk/sites/default/files/migrate/downloads/fix_dementia_care_homecare_report.pdf

[15] www.ageing-better.org.uk/publications/home-and-dry-need-decent-homes-later-life

[16] https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/908434/Disparities_in_the_risk_and_outcomes_of_COVID_August_2020_update.pdf

[17] www.alzheimers.org.uk/news/2020-06-23/ons-figures-show-almost-13000-people-who-died-covid-19-had-dementia

[18] www.alzheimers.org.uk/news/2020-06-04/coronavirus-social-contact-dementia

[19] www.rtpi.org.uk/news/plan-the-world-we-need/about-the-campaign/

[20] https://actonalz.org/sites/default/files/documents/Dementia_friendly_communities_full_report.pdf

[21] www.alzheimers.org.uk/blog/coronavirus-social-isolation-dementia-diary-keith-olive

[22] www.innovationsindementia.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/DementiaCapableCommunities_summaryFeb2011.pdf

[23] Ibid

[24]www.alzheimers.org.uk/sites/default/files/migrate/downloads/dementia_2013_the_hidden_voice_of_loneliness.pdf

[25] www.idgo.ac.uk/about_idgo/docs/NfL-FL.pdf

[26] www.alzheimers.org.uk/dementia-professionals/dementia-experience-toolkit/real-life-examples/dementia-friendly/turning-volume-living-dementia