The RTPI aims to promote a wide variety of views in its blog section. The views expressed by authors are their own and do not necessarily reflect the views of the RTPI.

Marijke Ransom MRTPI, was awarded the RTPI Practitioner Research Fund award in 2019.

Marijke Ransom MRTPI, was awarded the RTPI Practitioner Research Fund award in 2019.

'Sustainable development', while being the overarching goal of planning and resource management decisions around the world for more than 30 years, has proved to be an elusive target. Despite the best intentions of both legislated and even 'best practice' decision making frameworks, the quality of the environment and health of ecosystems has continued to decline. The dire state of global natural resources has led international experts to warn that the delivery of the re-affirmed international Sustainable Development Goals can now only be achieved through 'transformative change' – described as a fundamental, system wide reorganisation across technological, economic and social factors, including paradigms, goals and values (IPBES, 2019, p.14).

In Aotearoa New Zealand, the Treaty of Waitangi signed in 1840 between the British Crown and over 500 Māori Rangatira (chiefs/leaders) is providing a catalyst for envisioning what this transformative change might look and feel like. In the context of growing inequality, declining health of natural resources and vulnerability of the NZ economy, the obligation under the Treaty of Waitangi to protect Māori culture and to enable Māori to continue to live in New Zealand as Māori, is bringing 'tikanga' based frameworks to the fore across government policy.

In New Zealand the Treaty of Waitangi is regarded as an impetus to manifest this change that could be an example for the rest of the world.

He Ara Waiora is a model for analysing and measuring wellbeing developed by the Tax Working Group. Still under development, the framework has been informed by expertise and commentary on the contemporary application of tribal and traditional Māori concepts, religion and philosophies to guide proposed reforms to the taxation system.

At the heart of the He Ara Waiora model is the concept of whakapapa – which connects people to the environment and to each other. The He Ara Waiora framework has sought to reflect and conceptualise how many historical and contemporary Maori entities ensure that the decisions they make do not prioritise an economic bottom line but values collective and environmental benefits.

Throughout engagement with Māori, there were consistent recommendations that He Ara Waiora should be aligned to Treasury's Living Standards Framework and apply across all Crown policy. An immediate challenge is how this transformative thinking may be reflected and embedded into forthcoming reforms to the Resource Management Act (RMA) in New Zealand.

Designers of the He Ara Waiora framework warn that it is important that tikanga is not diluted or misrepresented by being 'bolted' onto a framework that comes from a philosophical tradition that is at odds with a Māori worldview. Whilst the 'four capitals' approach (natural, social, human and; financial and physical) in the Living Standards Framework is seen as a popular means to embrace a holistic and integrated approach to wellbeing, it is considered to be ultimately human-centric and not sufficiently fulsome to reflect a Māori view of wellbeing.

A number of key debates are signalled and triggered by changes suggested by the Minister for the Environment to the recommendations made by the Resource Management Review Panel. Current proposals includes repealing and replacing the Resource Management Act within this term of Government with 3 Acts – Natural and Built Environment Act (NBA), Strategic Planning Act (SPA) and Managed Retreat and Climate Change Act. The purpose of the NBA is intended to give effect to the principles of the Treaty of Waitangi concurrently, restore and maintain biophysical bottom lines; and achieve positive outcomes.

In collaboration with Professor Alister Scott at Northumbria University, I used the RTPI Practitioner Research Fund award to develop an ecosystem services based policy assessment framework for the Aotearoa New Zealand context. This policy assessment tool was tested on a combined Regional (land, air and water plan) and District (development and subdivision plan) level for the Tasman Region at the top of the South Island. It adapted the Green Infrastructure Policy Assessment Tool developed in the UK by Scott and Hislop and integrates Maturanga Māori values derived from the Te Aranga Landscape Strategy used in the Auckland Council Design Manual, being:

|

Maori Principle |

Outcome |

|

Mana |

The status of iwi and hapū as mana whenua is recognised and respected |

|

Whakapapa |

Māori names are celebrated |

|

Taiao |

The natural environment is protected, restored and/or enhanced. |

|

Mauri Tū |

Environmental health is protected, maintained and/or enhanced. |

|

Mahi Toi |

Iwi / hapu narratives are captured and expressed creatively and appropriately. |

|

Tohu |

Mana whenua significant sites and cultural landmarks are acknowledged |

|

Ahi Kā |

Iwi / hapu have a living and enduring presence and are secure and valued within their rohe |

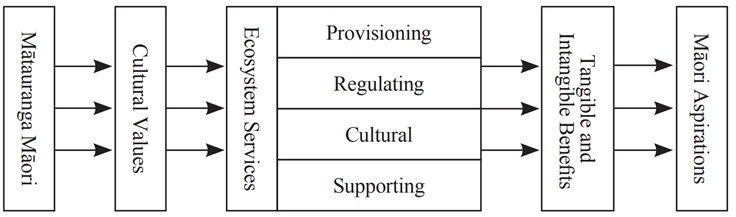

The policy assessment tool builds on earlier research comparing Maturanga Māori ((Māori knowledge systems) and Ecosystem Services in NZ in 2013 which suggested that there is a high degree of alignment between Ecosystem Services and Maturanga Māori. Though rather than limiting the integration of Māori values to 'cultural services' Harmsworth & Awatere (2013) presents Mātauranga Māori as a parallel framework that can underpin the delivery of ecosystem services rather than being simply accommodated within.

Figure 1: A māori ecosystem services framework uses cultural values to underpin all ecosystem services – provisioning, regulating, cultural and supporting – not just cultural services. (Source Harmsworth and Awatere 2013, p294).

From a planning practitioner’s perspective the framework, comprising 26 assessment criteria, is useful for identifying policy gaps and deficiencies and facilitating discussion about where policy improvements can be made. Further engagement with Māori to refine the tool and develop model policies has been recognised. It will be critical to demonstrate that decision making under the policy framework aligns with a Māori led tikanga.

Experience in Aotearoa provides examples of how traditional cultural values enables holistic decision making, delivering shared objectives that are consistent with the Ecosystem Approach, which include: the conservation/restoration of ecosystem structure and functioning; the sustainable use of natural resources; and the fair and equitable sharing of the benefits that arise out of the use of natural resources. The examples using Maturanga Māori paradigms, goals and values in a contemporary context provide an example of what 'transformative change' could look and feel like for the rest of the world. The experience also highlights some of the challenges and resistance to enabling this transformative change.

Marijke Ransom

Marijke Ransom been a full member of the New Zealand Planning Institute (NZPI) and the Royal Town Planning Institute (RTPI) since 2009 and 2016 respectively. She currently works at Tasman District Council as a subdivision consent planner. Her planning journey started in 2000 at Winchester District Council on the review of their Local Plan. She worked in several different planning roles in the UK and New Zealand before returning permanently to New Zealand in 2017. She was awarded the RTPI Practitioner Research Fund in 2019.