This research considers how local authorities can measure the outcomes of planning. This means going beyond simple metrics like speed of processing applications and number of housing units delivered and assessing planning in terms of placemaking aspirations and social, economic and environmental value, in order to track and improve the impact of planning.

This research considers how local authorities can measure the outcomes of planning. This means going beyond simple metrics like speed of processing applications and number of housing units delivered and assessing planning in terms of placemaking aspirations and social, economic and environmental value, in order to track and improve the impact of planning.

Building on previous work that has taken place across the nations, the research team reviewed the context and needs of planning jurisdictions across the UK and Ireland, identifying guiding principles, developing a toolkit and then contextualising, testing and refining that toolkit.

The project has culminated in the development of a report and series of toolkits which can be adapted by local planning authorities across the UK and Ireland to improve their outcome measurement.

This research was commissioned by the Royal Town Planning Institute (RTPI) with funding support from the Governments of Ireland, Scotland and Wales, along with the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government and the Office of the Planning Regulator in Ireland.

The research was delivered by a consortium of planning consultancies and academics from around the UK and Ireland, led by Kevin Murray Associates with support from Cardiff University, the University of Dundee, MacCabe Durney Barnes, and Yellow Book Ltd.

The research toolkit

The research has resulted in a series of documents, including a research report (see below), a Measuring What Matters, Planning Outcomes Toolkit (which can be adapted to any nation) and a handbook to accompany the toolkit.

The toolkit was tested through pilots in Ireland and Scotland and work was also carried out in Wales to produce a toolkit relevant to the Welsh context. You can view the Scottish Toolkit and information here, Irish Toolkit and information here and Wales Toolkit and information here.

Visit our RTPI YouTube page to hear the research team behind the RTPI Measuring What Matters: Planning Outcomes Research discuss planning outcomes and the research toolkit.

Read the report

Click here to download the Measuring What Matters: Planning Outcomes Research Report and separate appendices or read the research report including appendices below:

RTPI champions the power of planning in creating prosperous places and vibrant communities. We have over 25000 members in the private, public, academic and voluntary sectors. Using our expertise and research we bring evidence and thought leadership to shape planning policies and thinking, putting the profession at the heart of society's big debates. We set the standards of planning education and professional behaviour that give our members, wherever they work in the world, a unique ability to meet complex economic, social and environmental challenges.

About this paper

This research was commissioned by the Royal Town Planning Institute (RTPI) and jointly funded by the Governments of Ireland, Scotland and Wales, along with the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government and the Office of the Planning Regulator in Ireland. The RTPI is very grateful to the project partners for their support in taking forward this work.

The research was delivered by a consortium of planning consultancies and academics from around the UK and Ireland, co-ordinated by Iain MacPherson MRTPI, with Kevin Murray FRTPI and Rim Chouaib MRTPI (Kevin Murray Associates), Dr Husam Al Waer MRTPI (University of Dundee), Dr Neil Harris MRTPI and Dr Brian Webb AssocRTPI (Cardiff University), Jerry Barnes MRTPI and Sybil Berne (MacCabe Durney Barnes) and John Lord (yellow book). The diversity of experience and perspectives this team brought to the project has helped inform not only the research process, but also in generating a set of practical toolkit outputs.

We would also like to thank the members of the Client Advisory Group, Chris Sinclair (Scottish Government), Sarah Shaw and Christine Cox (Heads of Planning Scotland), Niall Cussen, Sinéad Mullen and Gary Ryan (Office of the Planning Regulator, Ireland), Niamh Hanrahan and Colin Fulcher (Department of Housing, Local Government and Heritage, Ireland), Neil Hemington and Amy Ravitz-Williams (Welsh Government), Gareth Jones (Planning Officers Society Wales), Suzanne Walpole (Ministry for Housing Communities and Local Government, England) and Nick Porter (District Councils Network) for their time, guidance and advice.

In particular we would like to express our gratitude to the many individuals and organisations from across the UK and Ireland who took part in the Pilots (Loch Lomond and the Trossachs National Park, City of Edinburgh Council, North Lanarkshire Council and The Highland Council in Scotland, Eastern and Midland Region, Donegal County, Clare County Council and Dún Laoghaire Rathdown County Council in Ireland), Focus Groups, interviews and surveys, and gave up their time to provide valued views which have helped to inform this work.

Contents

Executive Summary

1.1. Why use this tool?

1.2. How is the tool to be used?

1.3. At which spatial scale is the tool applicable?

1.4. When to use the toolkit?

1.5. What are the benefits of using the tool?

1.6. Conclusion

1. Introduction

2. Why does measuring planning outcomes matter?

2.1. Literature review and evidence base

2.2. Linking to United Nation Sustainable Development Goals and National Outcomes

2.3. Challenge and Value

2.4. Moving from outputs to outcomes to impact

2.5. Users and Audiences

3. Research process and findings

3.1. Egan Wheel – Sustainable Communities

3.2. Sustainable Built Environment SuBETool Framework

3.3. RIBA Sustainable Outcomes Tool

3.4. ‘Le référentiel ‘Un aménagement durable pour la ville de Paris’ - Tool for evaluating the sustainability of urban places

3.5. Focus group key messages

3.6. Pilots and contextualisation

3.7. Scotland context and pilots

3.8. Key lessons from Scotland pilots

3.9. Ireland context and pilots

3.10. Key lessons from Ireland pilots

3.11. Wales contextualisation

3.12. Key messages from Scotland and Ireland pilot

4. The toolkit concept

4.1. Developing a toolkit

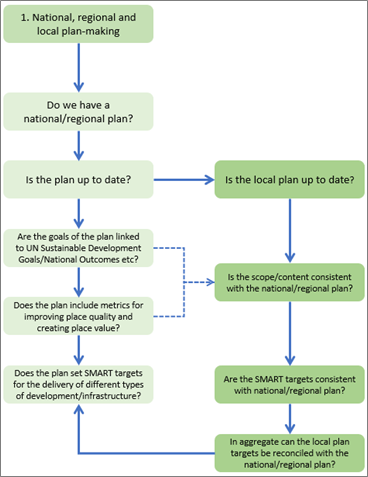

4.2. Outcomes – defined at plan level

4.3. Toolkit theme categories and indicators

4.4. Data sources

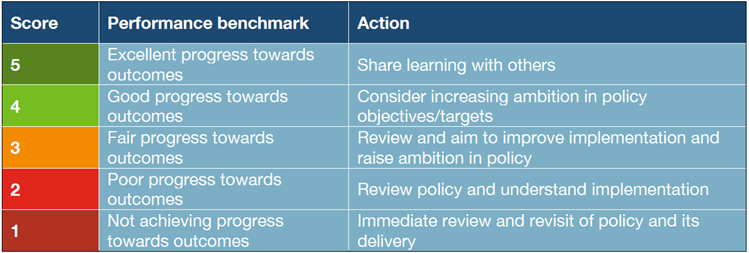

4.5. Scoring

4.6. Review

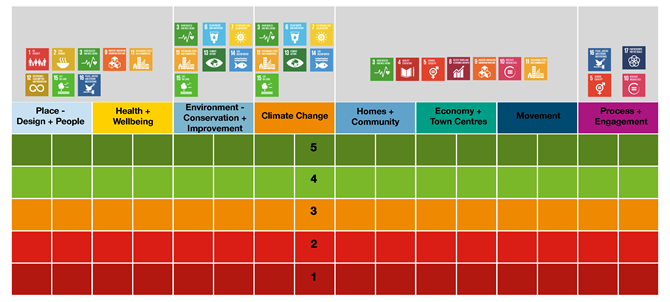

4.7. Visualisation of the toolkit results

5. The toolkit in practice

5.1. When to use the toolkit?

5.2. What are the benefits of using the tool?

6. Recommendations

References / Bibliography

Acronyms

Appendix A: Survey summary

Appendix B: Illustrative data mapping – Scotland and Ireland

Appendix C: Developing the toolkit – a worked example

Executive Summary

The philosophy and practice of planning have become more complex in the last twenty years. The scope of challenges nationally and locally has led to shifts in legislation, policy and in expectations of planning. The Royal Town Planning Institute and its partners across different jurisdictions now seek better mechanisms to track future performance against this changing background, looking beyond measurement of processing speed and simple outputs.

Building on previous research that articulates these higher aspirations, the RTPI has commissioned this piece of research to help provide practical ways to gauge how planning delivers on the explicit aspirations of planners and elected representatives, in terms of placemaking and social, economic and environmental value.

This research report is accompanied by a suite of documents to deliver on the research aims. The report covers the research background, process and findings before presenting a practical toolkit that can be used to begin the process of measuring the impact of planning. There is a Handbook that offers practical guidance, documents on the pilots carried out in Ireland and Scotland (including worked examples of a first cycle of toolkit use), the Welsh contextualisation and finally excel sheets providing the practical framework for implementing this new process of measurement.

Bearing in mind that recent planning legislation and policy in Ireland, Scotland and Wales, as well as the UN Sustainable Development Goals (UN SDGs), confirm this directional shift, the toolkit has a complex set of performance parameters to address. This involves shifting measurement beyond narrow development outputs to consideration of wider place outcomes and impacts. In addition, the toolkit needs to be flexible and adaptable, able to be used in different jurisdictions, and to respond and aid performance improvement over multiple monitoring cycles.

A research team led by Kevin Murray Associates[1] has reviewed the context and needs of each of the planning jurisdictions across the UK and Ireland. The stages of the research comprised:

Phase 1 – Finding the guiding principles

Phase 2 – Developing the base toolkit

Phase 3 – Contextualising and testing

Phase 4 – Refining and reporting

Through the consultative stages of the research it became clear that a sudden ‘switch’ to measuring the outcomes and impacts of planning poses operational, resource and data challenges. However, a staged transition towards a more ambitious approach is possible and we have accordingly developed a pathway with a measurement tool at its core.

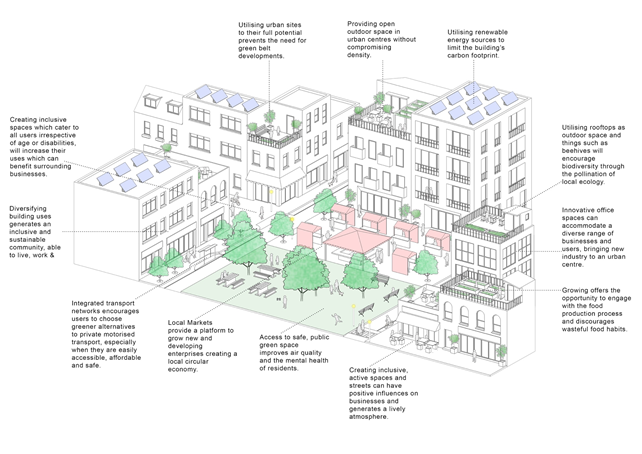

This toolkit will assist planning authorities and other users to gauge how planning policy and decision-making impacts on placemaking, including social, economic and environmental value. By using the toolkit and appropriate sectoral indicators, authorities and partner agencies should have the means to track performance, not only of those aspects directly attributable to planning, but also those areas where planning activity contributes indirectly to wider outcomes.

This document should therefore be read not only by planning professionals and fellow practitioners, but by politicians, civic and community representatives, and partner agencies in environment, economy, health and wellbeing who seek a more integrated set of place outcomes.

1.1. Why use this tool?

The primary function is to aid understanding of the impact of planning policy and development management in a geographic area. Where the data is available this can be aggregated up to regional and national levels. As the performance review material is built up over time the impacts on place creation can be captured, with the intention of progressively helping improve places and outcomes. The toolkit demonstrates the value of planning’s contribution to environmental, economic and societal outcomes, making it a useful evidence base across all levels of government.

The toolkit can also be used in collaboration with other agencies and sectors, to align strategic goals, indicators and investment priorities. The pathway can help planners and other partner agencies to focus on integrated outcomes within defined territory.

1.2. How is the tool to be used?

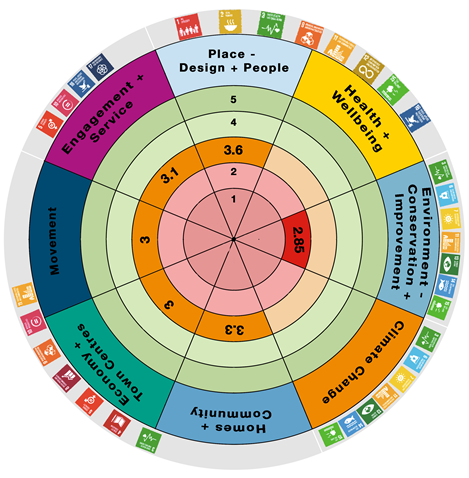

The tool enables the integration of multiple areas of change and influence of the planning system within a single format. The research has identified eight outcome themes:

- Place – design and people

- Health and wellbeing

- Environment – conservation and improvement

- Climate change

- Homes and community

- Movement

- Economy and town centres

- Process and engagement

These support the alignment between planning and national and international outcomes.

The idea is to initially use data that is already available within planning, local authority or other agency tracking – rather than generate new measures. The tool can be applied as part of an annual monitoring process or as part of a plan-making and implementation cycle. The tool is ready to use for any plan regardless of its stage, ideally where there are clear targets or objectives that can be tracked by indicators, but it can also help set these.

The pathway indicates how it is possible, if data is tracked over cycles, to move up levels to increase the focus on higher levels of place outcome.

1.3. At which spatial scale is the tool applicable?

The tool is flexible enough to be applied to any spatial scale where there are a set of objectives and/or policies. This includes use within different national jurisdictions. Typical levels would be at local authority level, or at development plan level.

The tool can potentially be used at the spatial scales of a town or city, rural area or even a coherent neighbourhood or masterplan area. We have already piloted the toolkit based on Local Development Plans, Regional Plans and Energy Plans. The application of the toolkit depends upon having a set of objectives, and appropriate measurable indicators against which to track performance, or to use it to assist in setting these.

1.4. When to use the toolkit?

The toolkit can be used as a reflective analytical tool at the start of a plan preparation process. The review of a pre-existing plan can demonstrate the impact that the plan has had over the course of its life. The performance review can also provide an evidence base for what needs to be adjusted in any new/update plan or in development management decisions.

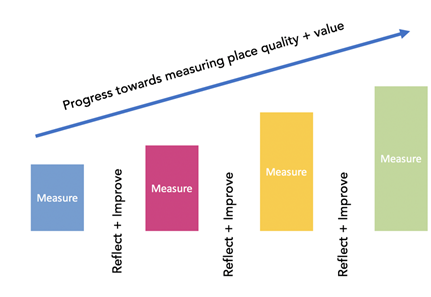

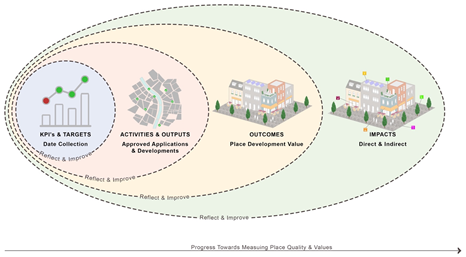

Figure 1: Toolkit entails a cycle of evaluation that can both measure and aid improvement

The tool is to be used in an overall performance monitoring cycle, with diagnosis, review and implementation built into its process. For a development plan this would include a baseline stage, mid-plan review and review ahead of the next iteration of the plan.

Other timeframe applications are possible and could be subject/theme specific. To review the relationship between adopted policy and development management decisions, for example in relation to climate change, decarbonisation or health and well-being.

Another use may be to refine a plan mid-cycle. The climate emergency and Covid-19 crisis flag up that action needs to be taken immediately and planning can play a critical role in this without waiting for the formal process of creating a new plan. The tool can help review existing performance and identify areas where additional guidance or mid-plan policy adjustments need to be made.

The tool would also make a useful basis for comprehensively assessing determinations made through the various appeal systems. This could provide a valuable transparent evaluation of such decisions and the degree to which they comply with local and national policy.

It is envisaged that, at least initially, the primary users of the toolkit will be planning authorities, along with performance monitoring colleagues in both national and local government. Initial use of the toolkit builds upon existing data and material. To be effective in building up data coverage and analysing performance across wider sectors will require input from economic development, environmental and health agencies, so they will also be contributors, users and potential beneficiaries in tracking the planning contribution to their strategies and goals, using the toolkit in an integrated approach to place.

Once the toolkit and data are available, we can see a wider range of beneficial users including

- Citizens, civic groups, residents and business stakeholders within the area who need to measure place-based outcomes (for example for funding reporting).

- Developers, investors and consultants behind key masterplan and development projects, looking to ensure that their proposals are outcomes-based and compliant with wider aims.

- Researchers such as universities, professional bodies and even the local and national media (consider interest in Covid-19 statistics).

- New cross sectoral planning partnerships – e.g. public-private or non-governmental organisations – as basis for tracking new plans and strategies.

Once established with publicly available data it should be possible for interested members of the public to use toolkit to aid the assessment of the impact of planning in their area. In much the same way that the Place Standard[2] tool has secured wider community application, the tool could be of interest to community groups and organisations concerned with the role and impact of planning.

To optimise the range of beneficiaries once established, it will be important that all material is publicly available across all sectors of indicator.

1.5. What are the benefits of using the tool?

The utility of the toolkit and the ‘results’ arising from its use will include:

The utility of the toolkit and the ‘results’ arising from its use will include:

- Tracking performance/progress over time.

- Integration across policy sectors and themes.

- Understanding what has worked, what has not worked; identifying possible causes and what needs improving or abandoned in future.

- Informing Development Management and decision-making.

- Raising aspiration towards delivering better planning outcomes against strategies/plans/ policy goals.

- Visibility/transparency of outcomes and impacts at local levels.

- Aggregation and benchmarking of performance at regional and national scales.

- Raising shared factual/scientific awareness between different parties and stakeholders.

- Educational dimension in terms of knowledge transfer, skills and awareness/use of data.

1.6. Conclusion

Although the tool has been researched and generated for peer to peer use within planning, it is clear that, once established, the toolkit has many potential applications, audiences and beneficiaries.

By providing the basis to move towards, and progressively evaluate, a whole systems approach to planning and placemaking, it makes the connection between policy, decision making and the quality of outcomes in social, economic, health and environmental terms.

Because it can be used to track performance using open shared data, it can be used both as an objective evaluation tool and, potentially, as an integrative/advocacy tool within Government and the corporate approaches of the public sector agencies.

It can also support the private and third sectors in developing higher performing placemaking in their investments, for instance in reducing carbon or improving health and wellbeing.

The toolkit affords the potential basis for monitoring, evaluating and then improving planning in the public interest, building confidence in the system based upon actual performance.

This all depends on the next stage of refinement and development, and ultimate adoption within different jurisdictions to suit their circumstances.

1. Introduction

This Measuring What Matters: Planning Outcomes research was commissioned by the Royal Town Planning Institute (RTPI) and the national Governments in Scotland, Ireland, Wales and along with the Ministry for Housing, Communities and Local Government and the Office of the Planning Regulator in Ireland. [3] The research team, led by Kevin Murray Associates, comprised yellow book, McCabe Durney Barnes, University of Dundee and Cardiff University, providing a mix of practitioners and practice-oriented academics who have extensive experience of working in planning throughout the UK and Ireland. The diversity of experience and perspectives this team brought to the project has helped inform not only the research process, but also generating a set of practical toolkit outputs.

Measuring planning outcomes is not necessarily new territory. There is a relative wealth of previous research in this area from which to draw. So why is this such a key piece of work for planners and planning at this moment in time?

Planning has undergone considerable change over the last decade or so. The 2008 Global Financial Crisis has left a long-lasting legacy on communities and their physical place, with many having a long and slow claw back. The climate emergency and health crises are putting pressure on society and on place. 2020 has seen floods cause huge levels of damage, followed quickly by the response to the Covid-19 crisis and lockdown. Both of these illustrate the need for places to be more resilient, and this is before accounting for chronic and systemic issues such as health inequalities and the need to meet carbon targets.

In addition, there are other pressures from reduced capital investment in communities and constrained local service delivery. While these may not all be strictly planning issues, they are factors connected to place quality and liveability.

For planning, in practical terms, this has meant a system that is increasingly being pressurised to focus on delivering a service to immediate plan-users, seeking out efficiencies and generating revenue, rather than an outcome focus. With a growing dislocation between plan-making and development management there has emerged a drive to measure performance: in consents granted and units delivered. If ‘you are what you measure’, then this has increasingly left us with a system in which success is viewed narrowly through the prism of process performance outputs, rather than wider quality of life and physical place outcomes. At a time when we need a response to economic, environmental and societal pressures, planning needs to demonstrate that it can deliver in the wider and longer-term public interest.

The research approach comprised the following elements:

First, we sought to identify what planning systems are trying to deliver across Ireland and the constituent planning jurisdictions of the UK. How do we measure performance of this delivery now? If we are seeking better place outcomes, what should we be measuring?

Second, we considered what data sets and digital solutions are available to help enable the measurement of outcomes. We aimed to develop something that is useful, practical and is not a large additional burden to any authority or other user; otherwise it will not be used.

Third, we have developed and piloted a toolkit for measuring planning outcomes. Drawing ideas and suggestions from performance management and sustainability research, as well as planning research, we have evolved and tested the toolkit with different participants. To avoid creating something that becomes either onerous or unthinking box-ticking, the emphasis has been on practicality and utility.

To help contextualise this toolkit for the respective planning jurisdictions, we have run pilot exercises in Ireland and Scotland, and developed a contextualised tool for Wales. These have helped to explore and test the utility of the tool, exposing where it may be less practical and enabling changes to be made to improve efficacy.

Although the explanation may make the process sound simple, there has been a lot of complexity and diverse practice to unravel. If it were really so simple planners would probably already be measuring outcomes. Part of this complexity is picked up by Al Waer:

“planning for outcome oriented place [is] a moving target where there is neither a ‘state to be reached’ nor a ‘one-size-fits-all’ solution”.[4] For example, “healthy/well-being outcomes do not happen as an outcome in a ‘predetermined way’. It requires to be carefully discussed, openly debated and even centrally planned.” [5]

Our research has discovered there is a groundswell of enthusiasm within planning for this outcome-focused approach. It touches at the very heart of why so many planners have entered the profession in the first place. They want to have a meaningful impact on place and its communities; if they are what they measure, they want to know what that impact is.

This report sets out the baseline evidence and learning from the research, the toolkit concept and the toolkit itself. This aims to be a practical document and is accompanied by a separate “handbook” that can be used for quick reference around the jurisdiction contexts and in practice used alongside the toolkit documents which can be downloaded in excel format from the RTPI project page.

We also consider this to be the continuation of an ongoing evolution, although accelerating that process. As such we make a series of recommendations around next steps and implementation. This will not be a quick process. Work can and should begin now, but it needs to be ongoing. The benefits to planning, to place and to wider society will be far reaching if we can measure impact, learn from this and create places with the right outcomes.

2. Why does measuring planning outcomes matter?

2.1. Literature review and evidence base

Our review has drawn from academic publications on planning and sustainability, previous research on planning monitoring and outcomes, and other review literature on policy. We have also looked to other disciplines such as community learning for lessons on how their area of practice defines the monitoring and evaluation of its activity, inputs, outputs, outcomes and impacts.

The line of thinking emerging from the literature review is as follows:

- First, statutory planning has some established methods of monitoring across different jurisdictions, but these neither lead towards, nor equate to, a broad understanding of what planning actually achieves in terms of delivering better places. There is a consensual recognition that planning has a broader and longer-term impact, but that this is not systematically captured and demonstrated.

- Second, monitoring and evaluation are part of a longitudinal process, not a single moment in time. Such monitoring and evaluation takes place at different scales. These time and scale factors are complex, reflecting the reality of dynamic places where change is rarely driven by a single factor. In this sense, monitoring and evaluation of planning is not really about simplistic cause and effect, as may occur with other systems, but about understanding and measuring place-impact. Measuring what change occurs at different scales (and the subsequent impact on people’s lives, nature and the built environment) becomes the objective, rather than counting units, speed of decisions or whether a single policy has been delivered.

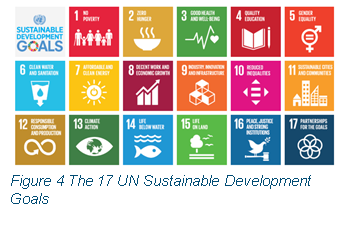

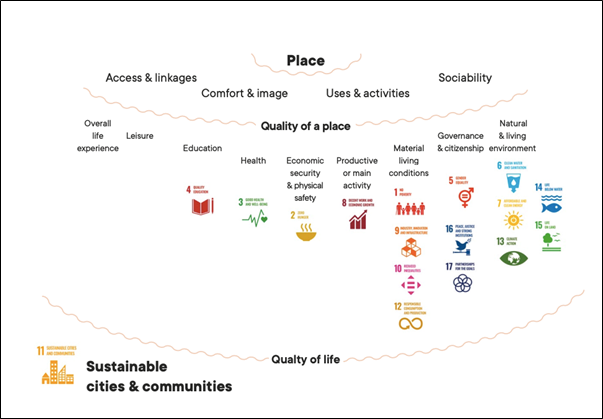

Third, there needs to be a higher-level anchor for this process. This could be supplied by maintaining alignment with the accepted outcomes in the UN Sustainable Development Goals[6] (UN SDGs) that have been adopted and adapted by national governments.

Third, there needs to be a higher-level anchor for this process. This could be supplied by maintaining alignment with the accepted outcomes in the UN Sustainable Development Goals[6] (UN SDGs) that have been adopted and adapted by national governments.

Effective proactive planning can contribute to the creation of successful places, which in turn can produce considerable economic, social and environmental benefits for society over the medium-term[7]. The recently published work commissioned by the RTPI Invest and Prosper demonstrates these benefits, and can put a monetary value on this[8]. Local planning authorities use planning policy and the process to articulate and deliver their spatial objectives respectively. By producing monitoring reports, they can demonstrate to the local authority, its partners and residents the progress towards their adopted plan, identifying the extent to which policy goals are being met and altering those which need to be amended. Planning authorities use a mix of qualitative and quantitative indicators to document planning activities and some make use of case studies to explain successful outcomes.

Planning Authorities in Scotland produce an annual Planning Performance Framework (PPF) to report on their own planning service. The PPF has been in operation for eight years, aiming to create a consistent method of measuring performance. Annual reporting has now been placed on a statutory basis by the Planning (Scotland) Act 2019. In England, Planning Authorities use Annual Monitoring Reports (AMR) to ‘advertise the achievements of good planning’[9]. Themes in the AMR are typically around the quality of development, planning performance, user and neighbourhood experience, and infrastructure delivery. In Wales, Local Planning Authorities produce an Annual Performance Report (APR) that uses a range of performance monitoring indicators to demonstrate how well authorities are performing, both individually and in relation to a Wales-wide context. In Northern Ireland the Planning Monitoring Framework (PMF) was introduced in 2019 to address the gap in the three statutory planning indicators. This introduced additional indicators to provide a more comprehensive assessment of planning activity and cover a wider perspective of the work of Planning Authorities. It presents a summary of the indicators for Northern Ireland, and other relevant indicator data for each local planning authority[10].

In Ireland, the Office of the Planning Regulator (OPR) is developing a Planning Performance Assessment Framework (PPAF) within which agreed process and outcome targets will be developed for performance and effectiveness measurement[11]. The PPAF will represent the OPR’s reporting mechanism for the oversight of the delivery of effective planning services to the public by Planning Authorities, and the performance by the An Bord Pleanála and Planning Authorities of their respective functions, as required under the Planning and Development Act. However, the PPAF will also consider the wider context of what constitutes proper planning and sustainable development and the planning and development system’s interaction with other social, economic and environmental processes and challenges.

Although these various monitoring reports provide a general picture of the ‘process performance’ of planning authorities, they rarely address that in terms of outcomes of planning, particularly when scaled up cumulatively over time in a neighbourhood, town or region. More and more, particularly since the evolution of integrative, spatial planning as expressed in the RTPI’s own New Vision for Planning[12], there has been a shift towards a place-based approach. Within this approach planning is expected

‘to deliver ‘better places’ or to contribute to wider policy goals such as health and wellbeing, learning, productivity, community cohesion and climate change resilience’[13].

Studies have been commissioned to address this ‘wicked problem’. In the Outcome Indicators for Spatial Planning in England – Framework Report15, Wong et al, looked at the objectives and desired outcomes of the spatial planning system in England. She described the outcomes of spatial planning as

‘derived from the objectives of planning. They are broadly drawn and will reflect more than just policy objectives, identifiable inputs or directly measurable outputs. Outcomes should be viewed as the combined effects on socio-economic and environmental changes brought about by the planning system and other forces that seek to achieve sustainable development and sustainable communities’.[14]

The study also highlighted the need to examine spatial outcomes at different scales, as there is a difference between the desired outcomes on a national scale and those at regional or local scale. Shahab et al, in Impact-based Planning Evaluation: Advancing Normative Criteria for Policy Analysis[15], advocates for an impact-based approach to planning evaluation that takes into account the intended and un-intended effect of public policy, as an alternative to the conformance-based evaluation approach. In that model, the success of a public policy instrument is built on the degree of conformity between the policy outcomes and its intended objectives without taking into consideration any unintended or secondary effects.

Traditionally, outcome monitoring has been predicated on a direct, linear ‘cause and effect14’ relationship between interventions and outcomes. The Scottish approach, for instance, is characterised by ‘a move within public services from top-down, service-led, reactive delivery, towards more personalised, preventative and collaborative ways of working’. It acknowledges that interventions interrelate with multiple other factors to influence outcomes[16]. Delivering Change18 is a policy document on understanding outcomes in community learning and development. This defines outcome as the changes that happen as a result of action, it recognises different types of outcomes, those that may occur rather quickly and as a direct result of the actions and long-term or end outcomes and are more difficult to measure[17].

In Ireland, the Planning Policy Statement[18] recognises the importance of ensuring quality of outcomes through the planning system.

“The success of our planning process will be judged by the quality of the places that result variously from, the development of new places, the regeneration of existing places and the protection or enhancement of places that are particularly sensitive because of the natural and/or cultural heritage or environment they contain.”

It also emphasised the need to deliver quality public services. The language of the Project Ireland 2040: National Planning Framework (NPF)[19] stresses the policy objectives of ensuring quality outcomes, valuing our environment and creating places where people will want to live, work and recreate.

When devising a tool to monitor the outcomes of planning, AlWaer et al[20] stressed that indicators should be chosen to link clearly between the objectives and outcomes, should be pre-defined and limited in number. They referenced Core Categories and Subcategories and recognised geographic variation, suggesting rural areas might need to have their own, different categories and indicators. They also emphasised the importance of timescale considerations because different indicators are measured across different timescales.

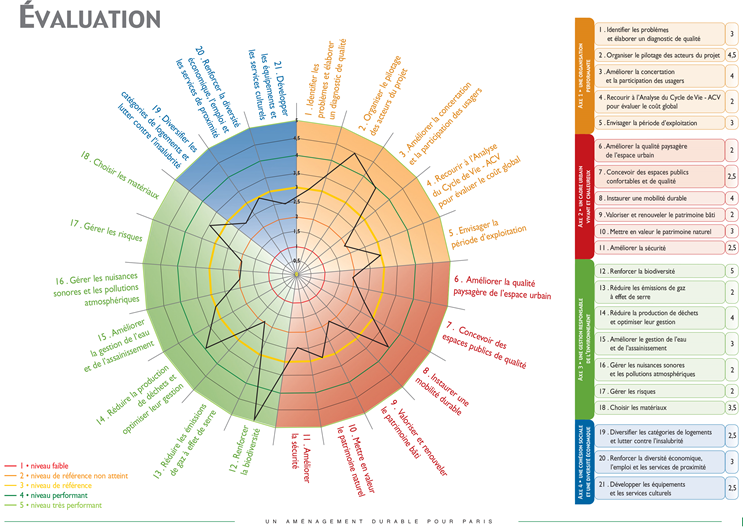

A useful monitoring and evaluation model developed in Paris as a sustainable urban development planning tool provides a system of indicators that take into consideration both the direct and indirect impact and the national/regional/local scales.[21]

These ‘Paris indicators’ take the form of an ‘active dashboard’ providing an on-going monitoring and evaluation operation over time. The dashboard is structured around four main axes and 21 objectives and brings together qualitative and quantitative indicators. These become the tool by which to gauge the outcomes over time. The indicators are measured at the different stages of a development project (design, works, management) on a scale of performance ranging from 1 to 5. Thus, the dashboard tracks two complementary objectives, evaluation and monitoring:

- Evaluate the performance levels in sustainable development of operations, with regard to the objectives targeted by municipal policy. This usage makes it possible to compare the performance levels achieved by operations, without losing sight of their own context;

- Ensure follow-up against the targeted objectives specific to each operation.

The Monitoring the Outcomes of Planning[22] study by yellow book demonstrated the support for moving towards a regime of outcome monitoring and impact evaluation and emphasis on the fact that monitoring should be a universal system and should capture outputs and outcomes from all planning applications.

The Place Standard2 tool, initially evolved by NHS Scotland, Architecture and Design Scotland and the Scottish Government, acknowledges, explores and records the performance of various facets that contribute to place quality and experience of it. It recognises that place outcomes are a composite of interacting factors and policies at different scales:

‘Place-based approaches help make the link between actions and wider outcomes and encourage us to Think Global and Act Local[23].’

This fairly simple multi-dimensional tool helps users to understand the connection between place, planning and outcomes.

Figure 5: Framework for sustainable communities and cities, UN SDGs

2.2. Linking to United Nation Sustainable Development Goals and National Outcomes

Although there is a current approach to monitor planning performance as a process in most jurisdictions, there is less evidence of tracking this against broader national and international objectives, although this is changing.

Understanding and evaluating the impact of planning in relation to higher level goals, such as the UN SDGs, or other national government outcomes tied to these, is ambitious and still in the early stages. Our survey evidence (Appendix A) suggests that while this is progressively being established in many places, there is still not necessarily a clear knowledge of what is being delivered through the planning system. If there can be more comprehensive data on the outcomes of a planning application for example, looking beyond simply number of units built, then evaluating the wider cumulative impact would represent a considerable leap in understanding performance.

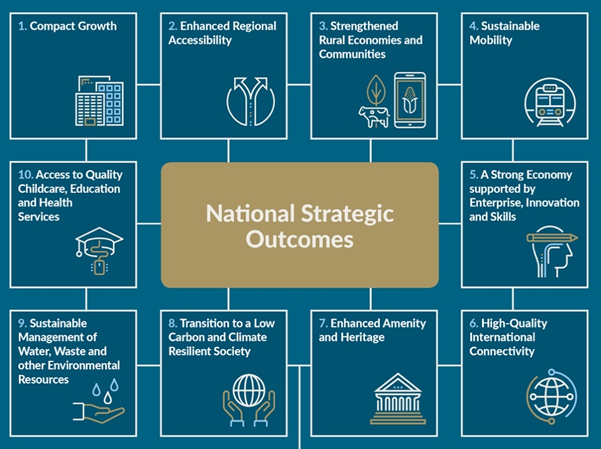

Figure 6: Ireland's National Strategic Outcomes - embedded in the National Plan and reflecting Ireland’s commitment to the UN SDGs

Ireland has established 10 National Strategic Outcomes under the Project Ireland 2040[24]: NPF which are linked to the UN SDGs and range from compact growth to ensuring access to quality childcare, education and health services. The Regional Assemblies and the Regional Spatial and Economic Strategies (RSES) play a unique role in translating between the national and local level policy frameworks. The Project Ireland 2040: NPF also identifies that the Office of the Planning Regulator (OPR)

“…will be responsible for monitoring and implementing the NPF[25] .”

To aid it in its future work, the OPR is developing a Planning Performance Assessment Framework (PPAF) within which process and outcome indicators are being considered for the measurement of performance across the planning system.

Figure 7: Scotland's National Performance Framework Outcomes, aligned with the UN SDGs

The Scottish Government has established eleven National Outcomes that “describe the kind of Scotland it aims to create[26]” and uses 81 National Indicators to measure the progress towards them. Performance is assessed as improving, maintaining or worsening based on the change between the last two data points of an indicator. All these outcomes align with the UN SDGs and the Scottish Government’s own Place Principle[27]. This is reflected in the high level outcomes stated in the upcoming National Planning Framework 4 (NPF4)[28].

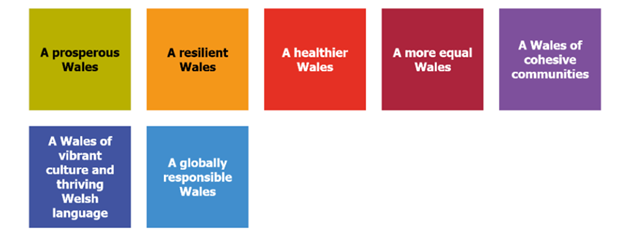

Figure 8: The Well-being Goals for Wales29 - embedded in commitment to UN SDGs

Wales has seven well-being goals that were established by the Welsh Government in the Well-being of Futures Generations (Wales) Act 2015. With the aim being to improve the social, economic, environmental and cultural well-being of Wales. In total some 46 national indicators have been selected by the Welsh Ministers as a reference framework, to measure performance against the goals. Each year a Well-being of Wales report[29] is released that provides an update of the progress, with a more detailed report produced every four to five years to review long-term performance.

In terms of planning more specifically, there is a combined All Wales Planning Annual Performance Report based on the Annual Performance Reports (APRs) submitted to the Welsh Government by Local Planning Authorities. This considers the operational performance of the planning system, including key trends in performance. The Wales Audit Office has published The Effectiveness of Local Planning Authorities in Wales that looks at

‘the progress of Local Planning Authorities in delivering their new responsibilities and the extent to which they are acting in accordance with the sustainable development principle contained within the Wellbeing of Future Generations (Wales) Act 2015. It also considers how efficient and effective the ‘local planning system’ is, focussing on their performance, income and expenditure to determine how resilient services are.’ [30]

Northern Ireland use the monitoring arrangements for the Programme for Government to show how progress is being made towards the UN SDGs. In other governmental departments, mapping exercises have been carried out to show how delivery plans align with these goals.[31] The UK Government notes that the best way to implement the UN SDGs is to embed these in the planned activity of government departments. A 2019 corporate report sets out some of the ways in which the UN SDGs are being implemented by the UK Government.[32]

2.3. Challenge and Value

The core purpose of the planning systems as they have evolved to date is built around the regulation of the use and development of land in the public interest. Recent iterations of legislation and national policy have broadened this core to embrace sustainable development, placemaking and wellbeing.

Effective planning helps to ensure economy, efficiency and amenity in the use of land, reconcile the needs of development and conservation, and protect natural resources and the historic environment. By fulfilling this core purpose and meeting agreed local performance targets, planning makes a direct and indirect contribution towards national and regional policy goals, and also, when tracked, to the UN SDGs.

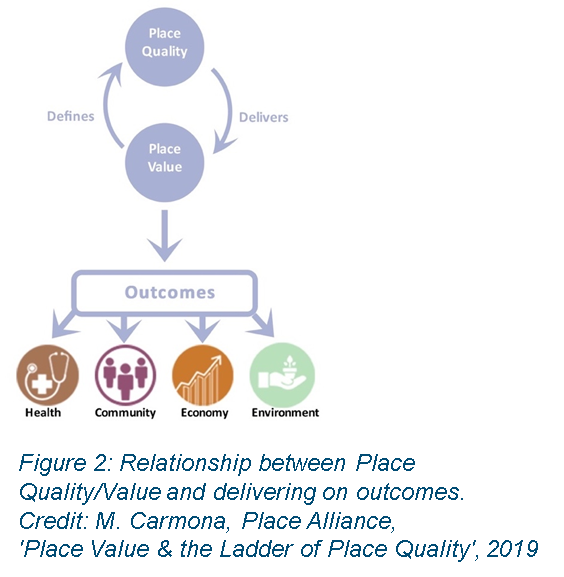

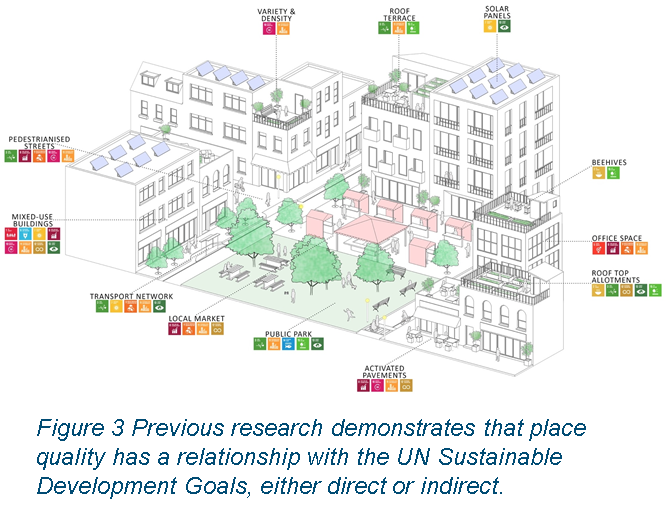

Sitting above its basic regulation of land use, planning also has a higher order role to create attractive, well-designed, sustainable places which will improve the quality of life of the people who live, work, learn and spend leisure time in them. Planners can help to achieve better place quality by, for example, publishing and applying design guidance and conducting design reviews. An extensive research literature attests that better design quality can also help to deliver place value in the form of positive health, social, economic and environmental impacts.[33]

Measuring the impact of planning on goals such as improving health or learning outcomes, promoting economic competitiveness or increasing biodiversity is inherently complex, but it is essential in order to determine whether (and how) the potential wider benefits of planning are being realised. Within such a broader measurement lies the key challenge around the question of attribution[34]: how can we demonstrate that what planning does has a contributory impact upon wider policy domains? A lot of progress has been made in this field in recent years, drawing on the growing body of research literature on how the built environment influences behaviour and wellbeing. By mining this body of research, policy makers and academics have been able to develop principles and standards that capture and codify place quality. Examples of this approach can be found in local design guides, the Scottish Government’s Place Standard2 and the recent Place Alliance31 report on Place Value & the Ladder of Place Quality, Creating Places for People in Ireland[35] and Places for Life from the Design Council for Wales[36]. Using these and similar tools we can frame SMART goals, performance indicators and targets which can act as reliable proxies for gauging place quality.

The toolkit presented in this report maps out the key levels in the evolution of an outcomes/impact monitoring framework for planning:

- The first level (Level 1) calls for the monitoring of planning activities, including plan-making, and the immediate, short-term outputs of those activities – for example, planning permissions granted (see Template Toolkit Level 1 tab for examples).

- The second level (Level 2) focuses on monitoring medium term planning outputs and development outcomes, notably the conversion of planning consents into development started and completed: at this point we can monitor progress towards the targets set out in development plans (See Template Toolkit Level 2 tab for examples).

- The third level (Level 3) takes us into the wider policy domain by focusing on the evaluation of place value and impacts resulting from the operation of the planning system: have new developments conformed to best practice in architecture and urban design, and what inferences can we draw in terms of their contribution to policy goals (see Template Toolkit Level 3 tab for examples).

2.4. Moving from outputs to outcomes to impact

There is significant variation in both the in-house performance management standards of different planning authorities and the reporting requirements of different jurisdictions. Consultations for this study suggest that most planning authorities are at Level 1 or Level 2. Level 2 might be considered to be the minimum requirement for effective performance management and democratic accountability. The study has also revealed an appetite among planning professionals to advance to Level 3. There is a desire to understand, quantify and publicise the benefits of planning for place value, balanced by an awareness of the methodological challenges and resource implications of commissioning evaluation studies. We have argued that Level 3 impact evaluation is only possible if robust Level 1-2 monitoring data are available.

Level 1-2 monitoring enables the development of a core set of metrics which can be used by policymakers, service managers, built environment professionals, researchers, the media and communities to:

- Make the planning system more transparent and accountable,

- Measure the efficiency, effectiveness and value of the planning system, and

- Benchmark the performance of planning authorities – being able to note improvement over time.

Level 3 performance management enables the same audiences to make informed judgements about:

- How the planning system can promote place value and place quality.

- The impacts of planning over time on place quality and wider societal goals.

- What works and what does not.

- Whether and to what extent the planning system is delivering better places.

2.5. Users and Audiences

To understand whether (and to what extent) planning is achieving its purpose we ideally need an outcomes monitoring framework which will:

- Establish performance indicators and tracking measures for the planning system.

- Set targets for planning activities, outputs and outcomes.

- Monitor the development plan and development management processes.

- Monitor the outcomes of the planning process in real places.

- Evaluate the direct impact of planning on place quality.

- Evaluate the indirect impacts of planning on health, social, economic and environmental place value.

Having a clear understanding of how the planning system is performing is important for:

- Politicians and policy makers (national, regional and local) who need to know whether the goals of national and regional planning policy are being achieved.

- Planning service managers, to help them understand whether their planning system and resourcing is operating efficiently and effectively, and to benchmark the progress of planning authorities.

- Planning authority practitioners, to help them to learn lessons from experience and modify practice to improve outcomes.

- Partner sectors and agency policymakers and analysts, to keep them informed of planning contribution and promote effective dialogue and alignment with the planning system.

- Wider community and civic groups, so that they can scrutinise the work of the planning system and call it to account.

- Applicants who wish to see how the planning fees they are paying into the system represent value for money.

3. Research process and findings

The project process can be characterised by the following four phases:

Phase 1 – Finding the guiding principles

A literature, policy and systems review and series of early consultations - the output was a working paper that included definitions around terminology to provide clarity for the next phase of engagement. The paper set out a draft set of guiding principles for the development of the toolkit. This informed the questionnaire and early development of the toolkit.

Phase 2 – Developing the base toolkit

This second phase involved engaging with a wider network of planning system operators (primarily local authority planners) to understand their needs and current measurement/monitoring regimes. This provided us guidance on what types of indicators the draft toolkit could and should potentially contain. The phase 2 output was captured in the Interim Report and comprised findings from our wider network engagement, the development process of the toolkit and presented a draft toolkit.

Phase 3 – Contextualising and testing

This stage provided an important opportunity to test the toolkit and to make amendments as necessary. We undertook contextualisation of the toolkit for Ireland, Scotland and Wales, receiving feedback on elements that worked well and less well. Phase 3 outputs were reported in a second working paper on the feedback, analysis and contextualisation of the toolkit testing.

Phase 4 – Refining and reporting

This final phase included holding online pilot sessions in Ireland and Scotland (we could not undertake in person sessions due to the Covid-19 pandemic). These explored contextualised toolkits for each of these jurisdictions and entailed a review with participating local authorities’ staff from different geographical locations in each country. These sessions became the basis for the drafting of this report and further refinement of the toolkit itself.

An integrated process of planning and development directed toward the vision of promoting place-based outcomes requires that targets are clear, progress is monitored, and performance is made transparent. The process of ongoing feedforward and feedback of such intelligence promotes adaptive planning that recognises complexity and relies on experimentation, learning, and capacity building. Accordingly, measuring planning outcomes need to be developed within an inclusive assessment framework, drawing together current performance frameworks with this approach in a collaborative manner with governments, planning authorities and users of the planning system. The assessment framework, adapted from Pearce[37] and Pearce and Barbier[38], needs to be informed by measurements and assessments that embody the following:

- The need for indicator sets that align development with a comprehensive setting of Sustainable Development Goals;

- Principles, goals, and standards;

- The importance of broadening the scope of how development is measured (i.e. this should have both qualitative and more readily measurable quantitative impacts; and

- The importance of extending assessment time horizons (including future generations among stakeholders), recognising the long-term consequences of actions, and anticipating long run pathways for managing the critical path to the desired future.

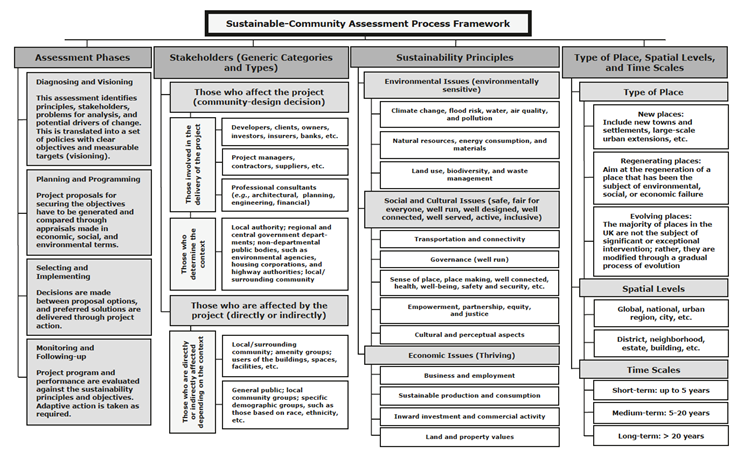

Figure 9 sets out the elements of a conceptual framework developed by AlWaer et al for measuring planning outcomes[39]. The figure below illustrates a general process covering the phases of issue shaping, setting goals and objectives, generating and comparing project options, selecting preferred solutions, implementing and subsequently monitoring those solutions, and evaluating performance. It identifies the mix of actors and the dimensions and time scales related to measuring sustainable place-based outcomes. Different sets of actors may be engaged at different stages of the process.

Figure 9: Sustainable Community Assessment Matrix, Al Waer et al 2014

We have reviewed a range of toolkits that are comparable to the product that would be required as a mechanism for tracking and measuring outcomes. The research team was already familiar with a number of these toolkits from previous experience with measurement and evaluation and have researched some new comparators through this project.

From the toolkits that we have reviewed, often generated for slightly different lead purposes, such as sustainable communities or masterplan performance, there is a broadly common structure. This structure creates a useful framework for understanding how a toolkit might function, on to which we can translate the needs of the Measuring What Matters project. Some of the key exemplars that have informed the generation of the toolkit are listed below.

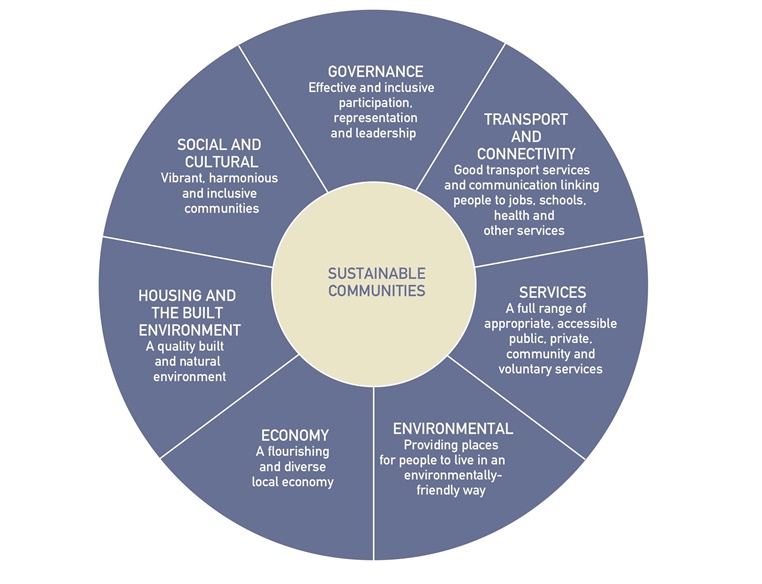

3.1. Egan Wheel – Sustainable Communities

As part of the Egan Review[40] into the skills required for establishing sustainable communities, led by Sir John Egan[41] this tool was developed to understand whether a place or community can be considered to be sustainable. The tool now turns out to relate to Sustainable Development Goals 11.

This tool identified seven thematic/policy areas of goal/target with a mix of objectives and 50 subjective/perceptual indicators within each. The tool acknowledges that some indicators will work better at different spatial scales than others. For example, economic performance indicators may work best at a city, region or sub-region scale, while indicators that use resident perception work better on a more localised scale.

This tool provides useful insight into building an evaluation framework, linking primarily existing indicators and data to a high level performance goal. The ability for this tool to work across different spatial scales is a key learning point, as is the aggregation of subjective data alongside more objective statistics.

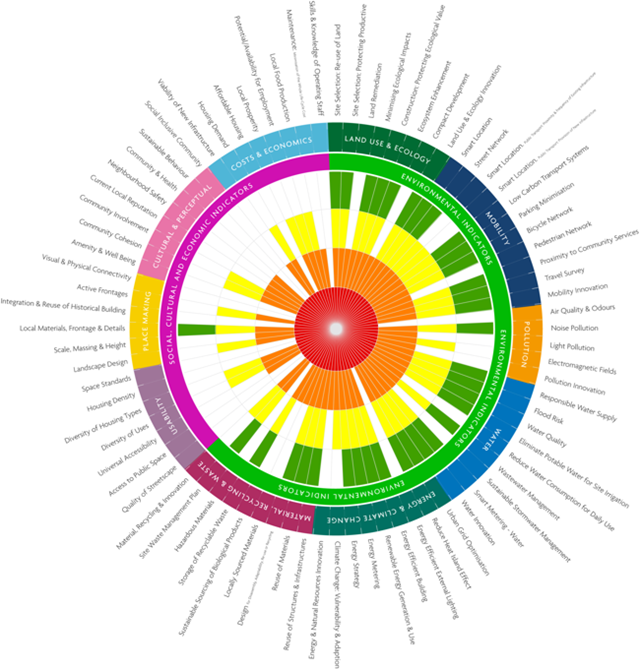

3.2. Sustainable Built Environment SuBETool Framework

SuBETool is a strategic planning and performance assessment methodology for spatial plans and masterplans, developed with University of Dundee, Hilson Moran and Reading University, and evolved from Dr AlWaer’s doctoral and post-doctoral focus on assessing sustainable development performance.[42]

The initial research objective was to critically examine linear-sequential models of assessment methods, including BREEAM Communities (UK), LEED ND (USA), and Green Star (Australia)

The development of the SuBETool highlights the multi-factorial nature of masterplanning and the requirement for a working consensus about critical issues, local values and their relative importance.

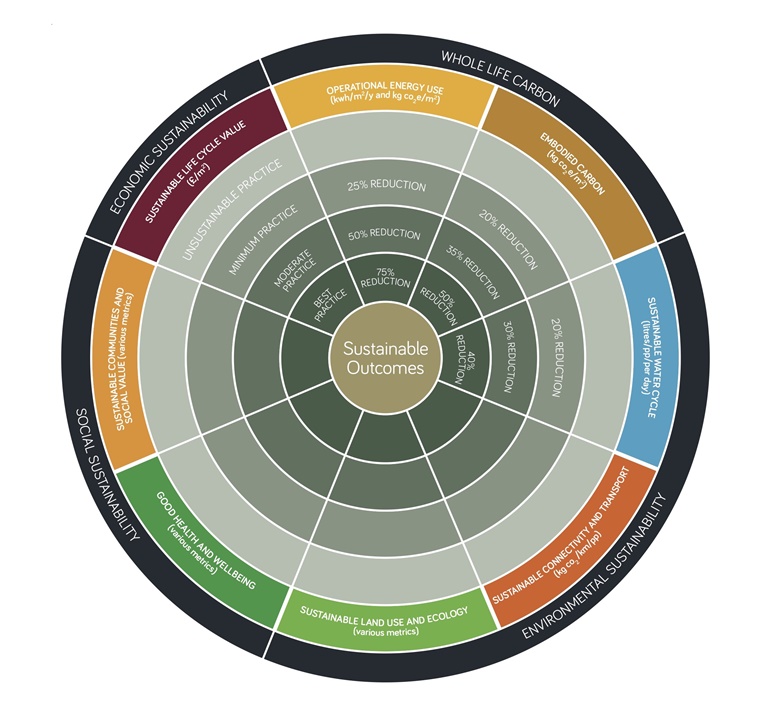

3.3. RIBA Sustainable Outcomes Tool

This tool has been developed to aid targeting, designing and evaluation of sustainable outcomes for buildings. The tool connects to the UN SDGs, identifying where sustainable buildings would make the most direct contribution towards these goals.[43]

The RIBA (Royal Institute for British Architects) tool makes this connection to higher level goals through four themes and eight outcomes. Using a blend of quantitative data around energy and resource use, plus factors around health and wellbeing, the tool uses a scale for each outcome that is relevant to the indicator, but still provides an overall picture of achieving the outcomes in a single, simple graphic.

3.4. ‘Le référentiel ‘Un aménagement durable pour la ville de Paris’ - Tool for evaluating the sustainability of urban places

This is a tool to enable follow up and evaluation of spatial planning operations (from forward planning to development management). Its role is to support the application of the Paris Plan Local d’Urbanisme (Local Development Plan) for the City of Paris (not the higher-level region, or the lower level districts)[44].

The tool was designed to ensure that the objectives of sustainable development were considered within spatial planning. It is principally used by the technical staff of the local authority, specifically the heads of the various departments. It also is applied to those providing a service to the City Authority, namely development agencies or approved housing bodies. It is applied at all levels of the planning hierarchy in the City, including project levels through all phases. It is based on four axes, with each axis accompanied by objectives and indicators.

An external evaluator is appointed to undertake the lower level evaluation of projects resulting from policies. These projects are generally best described as local authority or public private partnership led projects. To test this, they selected a sample of 20 projects to monitor over two years. The results of the evaluation then serve to revise policies and update objectives.

Summary: Key lessons from the different measuring tools

- The tools are anchored to higher level goals, primarily UN SDGs. Most look well beyond narrow ‘development outputs’ to consider wider economy, community, sustainability, health and quality of life aspects within their goals. Indicators for these provide a common reference point.

- The outcomes are not arbitrary, generic or top-down – they are specifically derived to address the issues and goals sought for the place, neighbourhood or building.

- These toolkits are generally set up to capture a measurement at a specific moment in time. The exercise needs to be repeated longitudinally to track trends of change and understand impact.

- A manageable number of outcomes are tracked. This ranges in number from 9 -21 per theme/category, with an effective number seeming to be around 14 – 15.

- Multiple indicators can be used to measure each outcome. Provided there is a relationship to the outcome/goal, the indicators can change to suit national/regional/local circumstances and data availability.

- Matching the right indicators to the right outcomes can be cautiously reverse engineered, based on available data. The caution is linked to limiting only to what is available, to avoid extra workload. This may need to be built up over time if new data gathering is required.

3.5. Focus group key messages

A series of online Focus Groups was undertaken following development of the draft toolkit with one held in each of Wales, Scotland, Ireland and England. The Focus Groups were shaped around ongoing lines of enquiry. While each geographical jurisdiction raised its own distinct set of messages, the following eleven key points were common across all of the Focus Groups.

A tool in the right direction

- Going beyond current metrics is desirable. The measurement of speed and number of applications does not provide an indication of the real impact that planning is having in a local authority area, nor at regional or national levels.

- A pragmatic pathway is required that starts with the current ‘position’ and information of planning authorities, reducing the need for additional data collection that isn’t already available in their own, or partners’, systems.

- Measuring what is happening on the ground in real places is key to understanding whether policy is having an impact – the tool needs to do this, or it will result in more of the same. Strategy and policy implementation are what is being measured – as there can be good policy but, without implementation, its impact is not realised.

- Tracking the right data sets over time will help to provide ‘read back’ on whether planning has had an impact; there is a need for consistency of measurement and process over these timescales to ensure accurate, comparable measurement.

- Guidance from governments on what should be measured would be welcome.

- Planning has a diminishing role once a planning application has been determined. There is a need for planners to make a big impact where they can in the process, and ideally to also remain linked to development post-decision. The practitioner skill, experience and judgement are key, notably in development management.

Areas for improvement

- Expansion of any monitoring role is not considered possible in planning authorities, given current resource levels – this would only be possible with further investment. This was a key concern from almost all who participated. They recognise that monitoring is already limited to what is absolutely necessary and additional monitoring would be very difficult to provide.

- Monitoring by an external party – such as Audit England, Office of the Planning Regulator, Regional Assemblies and the Department for Housing, Local Government and Heritage (DHLGH), (both Ireland) or the Planning Co-ordinator (Scotland) was advocated to ensure a degree of objectivity and address internal resource constraints within local authorities. The impact on behaviour/practice by such independent review needs to be acknowledged, as it could have a beneficial impact in altering outcomes.

Benefits

- The tool can be used to communicate with Chief Executive and Cabinet level in local authorities and other partner agencies, helping to monitor and align place-based decision making and assist the drive for a better place outcome.

- Making the case for appropriate resourcing – the tool can be used to aid identification of what and where specific needs arise. Rather than campaigning for more planners, a targeted business case can be made for a specific skill or expertise.

- Embedding the toolkit within the plan-making process, ideally at the outset of a new cycle of plan preparation, would provide a consistent method for ensuring impact can be properly considered throughout the formulation and implementation of a new plan.

3.6. Pilots and contextualisation

The pilots were run during the latter stages of the Covid-19 lockdown. They were conducted through a series of video calls, and the process of piloting was developed in partnership with the pilot areas. It was acknowleged that piloting would require simulated use of the toolkit given that the available timeframe and resource was restricted (and exaercabated by circumstances). Therefore the focus of the pilots was around the functionality of the diagnostic stage. The pilots provided insight to the team on the function of the toolkit and the role it can and should play in plan development and measuring of planning outcomes. We are very grateful to all those that participated and gave generously of their time.

3.7. Scotland context and pilots

In the next iteration of Scotland’s National Planning Framework 4 (NPF4)28 – there is a set of high-level outcomes:

- Meeting the housing needs of people living in Scotland including, in particular, the housing needs for older people and disabled people.

- Improving the health and well-being of people living in Scotland.

- Increasing the population of rural areas of Scotland.

- Improving equality and eliminating discrimination.

- Meeting any targets relating to the reduction of emissions of greenhouse gases.

- Securing positive effects for biodiversity.

This aligns with Scotland’s National Performance Framework, its expression of outcomes for the nation, and is tied to the UN SDGs. Within this there are two specific spatial outcomes articulated:

- NO 10: We live in well-designed, sustainable places where we are able to access the amenities and services we need.

- NO 12: We value and enjoy our built and natural environment and protect and enhance it for future generations.

The ‘non-process’ parts of planning are noted here, planning should be delivering quality, sustainability and ultimately better life outcomes through access to what we need. The current measurement of planning is heavily focused on process and not these attributes of the planning system. Previous research recommendations have suggested monitoring comes through an evolution of the Planning Performance Framework (PPF). This currently relies heavily on case studies.

Using the PPF and Annual Monitoring Statements helped set up a baseline run of the toolkit to pilot with the following authorities:

Highland Council

Based on the 2012 Highland-wide Local Development Plan. Pilot simulating an end of plan review.

Loch Lomond and the Trossachs National Park Authority

Based on the Loch Lomond and the Trossachs National Park Local Development Plan 2017 – 2018. Pilot simulating a mid-term review.

North Lanarkshire Council

Based on 2012 North Lanarkshire Local Development Plan. Pilot simulating an end of plan review.

City of Edinburgh Council

Based on 2016 Edinburgh Local Development Plan. Pilot simulating an end of plan review.

3.8. Key lessons from Scotland pilots

The following section provides a summary of the headline learning points drawn from the participants in the various pilot sessions.

The Highland Council

- The tool will be useful as an evidence base supporting current monitoring of effectiveness of policies in different geographies in Highland (very diverse local authority over a very large area).

- It aligns with current thinking to ensure that the Local Development Plan and all other strategies, whether top down or bottom up, are all pulling in the same direction.

- Aim is for every public investment to be making progress towards agreed outcomes – if the plan has this tool and process embedded it can help to deliver this.

- Data should be playing a new, stronger role in plan-making and monitoring. The role for data can be to assist in the evidence base for policy, and around supporting key planning decisions and asset management.

- Very important that Building Standards data should be drawn upon – it is accessible in Uniform (software system used by Scottish Local Authorities, provided by Idox) but the connections between planning permission and completion certificates still need to be made to close the evidence loop.

Loch Lomond and the Trossachs National Park

- The toolkit helpfully flags up what is not being monitored or looked at. Some of this can be accounted for by areas where there is not much development activity, but others suggest that policies may not be applied or used quite as intended. There is a process currently where the Development Plan and Development Management teams discuss policy, and this can provide an evidence base for these reviews and inform decision-making.

- Data for the National Park is complex, as many of the data collection geographies do not directly align with the National Park’s boundaries. Therefore finding data around some impacts will require additional work, either around understanding how existing data can be used, or gathering new data.

- It is crucial that there are good processes behind this measurement process, as with any monitoring. A good database, with helpful guidance notes are needed to ensure data gathered in a robust and credible manner.

North Lanarkshire Council

- A challenge remains around the attribution of some impacts to planning – how direct does this link need to be?

- The tool can assist in the alignment between the different plans for North Lanarkshire, including Single Outcome Agreements, Local Outcome Improvement Plans and Local Development Plans. These should be drawn together and all be pulling in the same direction.

- If policy or data inputs are too generic it may not be possible to track the performance. For example, policy on design quality that applies to the whole area can be very tricky to monitor. It may be easier when it more place specific.

- The tool provides an example of how national metrics might help. For instance, for 20-minute neighbourhoods (part of the Scottish Government’s policy agenda), a set of building blocks of what makes a good one could be articulated nationally, with performance tracking data collected locally.

City of Edinburgh Council

- The volume of information in the toolkit could and should be carefully whittled down and targeted. Not everything that is measurable needs to be included to demonstrate planning is contributing to outcomes.

- The tool can provide an important cultural/behavioural role within planning departments – if Development Management begins to build a sound evidence base from their decision making, it can build morale behind a shift towards an outcomes focus.

- To tool will help in formulation and developing of agreed, relevant performance targets.

- The process and tool can provide a comprehensive pulling together of plan and monitoring in one location. This gives a new insight, quickly identifying areas for further review.

- This could provide an important shift in the mindset, away from process and timescales, towards thinking about outcomes and impacts.

3.9. Ireland context and pilots

Ireland’s planning policy and administrative system is hierarchical in nature with the National Planning Framework’s national strategic objectives feeding into objectives of the Regional Spatial and Economic Strategies and then into the development plans of Local Planning Authorities.

Local Authority Performance Indicators have been developed by the National Oversight and Audit Commission (NOAC) established under the Local Government Reform Act 2014 and which can be deemed output indicators at the local level. The OPR is working with NOAC, the Department Housing, Local Government and Heritage and the wider local authority sector to develop a more comprehensive set of statistical indicators with which to oversee the performance of the planning authority sector. This expanded set of existing and newer indicators and sources of management information will be incorporated into the PPAF and will potentially include outcome indicators. At the current stage of development of PPAF, indicators will sit within one of three thematic categories: 1) Plan Led Development; 2) Managing for Sustainable Development; and 3) Delivering Quality Planning Services.

Currently, the implementation of local authority development plans is monitored through statutory monitoring reports and through Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) monitoring.

The pilots selected for Ireland reflected its hierarchical system of policy formulation and administration. The pilots also considered rural and urban contexts, different stages in the plan preparation cycle and sector specific spatial plans. Those selected for the pilots were:

The Regional Spatial and Economic Strategy for the Eastern and Midland Region 2019-2031

The pilot was at the start of the plan with a view to establish a monitoring regime.

The Donegal County Development Plan 2018-2024

The pilot was stimulating a mid-term review and it was used as a mechanism to inform the content of the next plan.

Clare County Council Wind Energy Strategy 2017-2023

The pilot was at the end of the strategy and it was used as a mechanism to inform the context of the new strategy.

Sandyford Urban Framework Plan 2016-2022

The pilot was at the end of their plan period and it was used as a mechanism to inform the content of the new plan.

3.10. Key lessons from Ireland pilots

Clare Wind Energy Strategy

- The toolkit helps us to rethink and re-evaluate the plan-making process and post-plan-making. It forces greater consideration of monitoring.

- Three people with different backgrounds carried out the scoring process, as it can be subjective and planning outcomes can mean different things to different people. The process of scoring was found to be as important as the score itself. The team review helps working toward a consensus and necessitates a dialogue to get to the score. The process is more important and it is at the heart of the purpose of plan-making.

- A standard set of indicators should be collected to feed back to regional level and national level. This would also help monitoring efforts, particularly with comparability of performance.

- Policies should be specific and measurable. Measuring more subjective policies will be more difficult.

- Relationship with strategic environmental appraisal (SEA) should be noted – in terms of purpose and type of data collected.

Sandyford Urban Framework Plan

- There is a nuance between outputs and outcomes. This process helps us reflect upon it.

- The themes give rise to quite a bit of crossover, in terms of where policies or indicators might lie.

- Scoring can only be done if the data to measure outcomes is readily available. It is easier to measure/score quantitative policies and objectives as these are either achieved or not achieved. It will be more difficult for assessing more qualitative policies.

- The toolkit might need to focus more on the strategic and ‘big ticket’ items to gauge impact, and see what datasets are available to support this. It is currently too detailed.

- The thematic approach can nevertheless assist monitoring and evaluation of different sectoral impacts. So it can add value.

Donegal County Development Plan

- This would be a useful tool to discuss the effectiveness of policies and objectives with elected members.

- It will be useful to help prepare plans which are concise, more readable, more focused, more pragmatic.

- The toolkit should be adaptable to a degree, and it could be used to draft development plans and contribute to their subsequent monitoring.

- Scoring would need to be carried by a team, including a range of disciplines, not simply planners ‘marking their own work’. Consideration might be given to having external assessment.

Eastern and Midland Regional and Spatial and Economic Strategy

- The toolkit is useful to measure the impact of policies further down the line in any timeframe, to see whether what these are trying to achieve has had any effect. It provides a reflection on policy-making and is also useful to measure progress on the delivery of specified objectives.

- Scoping the number of policies and objectives for review could be considered, as the task could be resource-hungry if it has to carried out across all 8 themes.

- Scoring could be carried out at several stages of plan-making, either at review stage or when starting out the next plan. We think collective scoring would be advisable and it is acknowledged that external scoring may be more robust as it is may be more objective.

- An element of coherence of input at lower level is necessary to be able to measure at higher level. To that effect, common indicators would be useful and these should be linked back to the National Planning Framework.

3.11. Wales contextualisation

The Measuring What Matters: Planning Outcomes toolkit in a Wales context is a mechanism to link national wellbeing goals and indicators, and national sustainable placemaking outcomes, with the review of Local Development Plans.

The Well-being of Future Generations (Wales) Act 2015 defines a series of goals, linked to a definition of sustainable development, and sets out methods of working towards these goals. Planning Policy Wales Ed.10 aims to maximise contributions to these goals by (1) promoting the concept of placemaking and (2) defining a series of ‘national sustainable placemaking outcomes’. Planning Policy Wales translates the well-being goals and ways of working into the planning system. There is nevertheless a need to strengthen how national planning policy connects with the practices of Local Planning Authorities.

The Welsh Government planning performance framework focuses principally on Local Planning Authorities and on process and efficiency indicators. Local Planning Authorities also issue their own Annual Monitoring Reports as a means of evaluating the implementation of their Local Development Plans. Reviews of the effectiveness of Local Planning Authorities raise some important concerns about how well they are connecting with the well-being agenda and goals. There are also significant concerns about the capacity of Local Planning Authorities to address this due to available resources. There has been work conducted in Wales in demonstrating the value of planning in Wales and this has attempted to align with the well-being goals.

Fuller contextualisation material for Wales can be found in the Measuring What Matters – Toolkit for Wales document.

3.12. Key messages from Scotland and Ireland pilots

The pilots allowed for a testing of the concepts, definitions and spreadsheets which underpin the toolkit. The spread of pilots covered different jurisdictions, spatial scales, geographical areas and types of plans. The following common practical lessons emerged from the pilots:

Different use depending on plan cycle

Several pilots were able to use the toolkit as a reflective plan-making tool utilised at the start of plan preparation, while others found it useful for mid-term monitoring of policy implementation.

Clear Understanding of Definitions

There is a need for a clear understanding of the distinction between outputs, outcomes and evaluation. Moving from measuring outputs to outcomes involves more qualitative assessment, which nonetheless should still be aligned to a robust baseline and which is capable of scoring and evaluation. If the toolkit is used at the start of a process as a plan-making tool, desired outcomes effectively become targets.

Providing a clear single-view of policy and monitoring

Drawing together plan, monitoring and performance material into one location in a comprehensive manner proved to be useful in diagnostic use. Highlights of where a plan or issue achievements are, or where there are gaps, can quickly be identified at this higher level. When going into more detail, the level of information becomes overwhelming. At the outset of toolkit use, it seems to be necessary to undertake this comprehensive exercise to identify what indicators and data sources provide a useful read on achievement in subsequent cycles. This process could also help to identify more clearly common and consistent indicators.

Extent of policies and objectives under review

Local development plans will include a wide range of policies and objectives. The resources will not necessarily be available to measure and evaluate the outcomes of all these provisions. A screening exercise can be undertaken at the start of the process to consider which key policies/objectives should be assessed. Due regard should be had to the requirements of monitoring and measuring outcomes at higher levels within the policy hierarchy. Consideration of the spatial application of the policy or objective should also be considered.

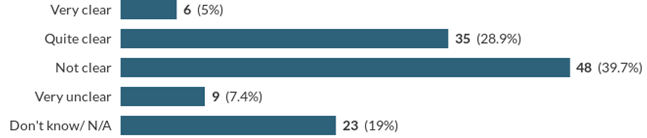

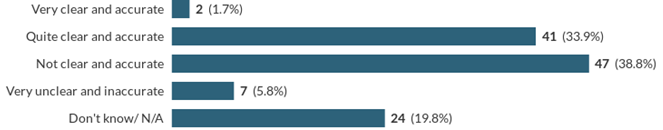

Developing an evidence base