When children and young people grow up in a quality built and natural environment it can have a positive impact on their health, well-being and future life chances. Good town planning should aim to meet children’s needs as part of an inclusive and integrated society. To do this effectively children should have a say in what these places look like. They should be actively engaged in the plan-making and design process. One of the aims of this advice is to expand the scope of what is currently understood as planning for children, beyond planning for play, towards a more inclusive approach that encompasses all aspects of children’s lives, highlighting the importance of the sustainable location of development that encourages independent and sustainable mobility.

When children and young people grow up in a quality built and natural environment it can have a positive impact on their health, well-being and future life chances. Good town planning should aim to meet children’s needs as part of an inclusive and integrated society. To do this effectively children should have a say in what these places look like. They should be actively engaged in the plan-making and design process. One of the aims of this advice is to expand the scope of what is currently understood as planning for children, beyond planning for play, towards a more inclusive approach that encompasses all aspects of children’s lives, highlighting the importance of the sustainable location of development that encourages independent and sustainable mobility.

This practice note gives advice on how town planners can work within the current UK and Ireland planning systems and with other professionals to plan child-friendly places. It summarises expert advice, outlines key planning policy and focuses on good practice through a series of case studies. It also outlines eight principles for designing child-friendly places. The policy context applies to England, Wales, Scotland, Northern Ireland and Ireland, but the principles of good practice apply wherever you work in the world. The audience for this advice is primarily RTPI members, but it is also relevant to other built environment professionals, advocates for children’s rights, charities and local politicians.

Download the full report here or read it below.

Download a summary here.

Contents

- Introduction

- About children

- Built environment and children

- Legislation and policy

- What does a place designed for children look like?

- Planning for children

- Design of children’s facilities

- Engaging children in town planning

- Further information

Acknowledgements:

Thank you to Tim Gill, author and children’s play and mobility advocate, Professor Peter Kraftl, Chair of Human Geography, University of Birmingham and Adrian Voce, Director of Playful Planet for sharing their time and expertise in contributing to and reviewing this advice.

Also thank you to Gabrielle Abadi and Lizzie Bird – London Borough of Hackney, Mark Dickens – Liverpool City Region Combined Authority, Catherine Greig – make:good, Brett Leahy - London Borough of Redbridge, Trovine Monteiro - Greater Cambridge Shared Planning, Callie Persic - Belfast City Council, James Virgo – Land Use Consultants, Susannah Walker and Imogen Clark - Make Space for Girls, Jenny Wood - A Place in Childhood, Frances Wright and Mike Bodkin – TOWN for their input.

1. Introduction

When children and young people grow up in a quality built and natural environment it can have a positive impact on their health, well-being and future life chances. Good town planning should aim to meet children’s needs as part of an inclusive and integrated society. To do this effectively children should have a say in what these places look like. They should be actively engaged in the plan-making and design process. Often children and young people use and understand the built environment in different ways to adults because they engage with it in different ways, for example through play and the type of facilities they use. One of the aims of this advice is to expand the scope of what is currently understood as planning for children, beyond planning for play, towards a more inclusive approach that encompasses all aspects of children’s lives, highlighting the importance of the sustainable location of development that encourages independent and sustainable mobility.

Around 20% of the population in the UK and Ireland is aged under 16[1]. However, as our review of ‘Child-Friendly Planning in the UK[2]’ concluded, the UK planning systems currently contain relatively little policy and guidance specific to children and young people. Children face many challenges that are directly related to the built environment. These include the high numbers of living in poor quality and overcrowded housing, in areas with high levels of pollution, or with limited access to quality greenspace and opportunities for play. Other challenges include the restrictions on movement posed by high levels of traffic, and the increasing impacts of climate change, amongst many others.

The impact of Covid-19 on children’s lives has been significant. Whilst relatively few children have become seriously ill with the disease, the impact of lockdowns, school closures, restrictions on the use of public spaces and reduced social interaction have been difficult for many. The long-term impacts on children’s health and development have not yet been fully assessed.

This practice note gives advice on how town planners can work within the current UK and Ireland planning systems and with other professionals to plan child-friendly places. It summarises expert advice, outlines key planning policy and focuses on good practice through a series of case studies.

The policy context applies to England, Wales, Scotland, Northern Ireland and Ireland, but the principles of good practice apply wherever you work in the world. The audience for this advice is primarily RTPI members, but it is also relevant to other built environment professionals, advocates for children’s rights, charities and local politicians.

2. About children

Before examining the impact of the built environment on children’s lives and the role of town planners in creating child-friendly places, this chapter outlines some of the current key statistical trends and challenges for children and young people in the UK and Ireland.

Children in numbers

Nearly 20% of the UK population were aged under 16 in 2019[3]. Similarly, 21% of the population of Ireland was estimated to be aged under 15 in 2021[4]. Some parts of the UK have higher than average numbers of children. This is the case in many large cities including London, Manchester, Birmingham, Cardiff, Glasgow and Edinburgh. The London borough of Barking and Dagenham had the highest percentage of the population aged 0-15 years at 27.2% in 2019. The Office for National Statistics (ONS) has a useful interactive map that shows how age structure projections by local authority over time from 2009 up to 2039[5].

In 2019 there were 712,680 live births in the UK. This is down from a peak of 813,000 births in 2012, since when there has been a steady decline[6]. In Ireland there were 55,959 births in 2020, the birth rate has also been in steady decline since 2012 according to the Central Statistics Office.

The proportion of mothers with children aged between three and four who are in employment increased by nearly 10% between 1997 and 2017 in the UK. In England 65% of mothers whose youngest child was a toddler, were employed in 2017. This was largely driven by an increase in full-time employment. During the same period, the number of fathers with young children who were working part-time also increased from 3.9% in 1997 to 6.9% in 2017. The ONS suggests that the changes are due to policy changes that introduced flexible working practices and shared parental leave[7].

Education

There were around ten million pupils at school in the UK in 2020. Nearly nine million in England, 469,000 in Wales, 794,000 in Scotland and 341,000 in Northern Ireland. They attended over 32,000 different schools[8]. The number of pupils in England is increasing, there were 71,000 more children in 2020 compared to 2019. The number of pupils increase in each year group from reception up to year three, before declining throughout subsequent year groups. According to the National Education Union[9] the average class size was 27.1 pupils for primary schools and 21.7 for secondary schools. However, these figures mask the differences across the country, with an overall increase in class sizes, with nearly one million pupils attending classes of 31 pupils or more.

The number of pupils in England who are eligible for free school meals is increasing. In 2020 17.3% of pupils were known to be eligible, increasing from 15.4% in 2019. The proportions are comparable for Scotland with around 17% of pupils receiving free school meals, but the figures are even higher for Wales at 20%, and in Northern Ireland it is 28% of pupils. These figures are expected to have increased further due to the Covid-19 pandemic[10].

There were more than one million pupils in primary schools recorded as having English as an additional language, with a further 584,600 pupils in secondary schools. Children who have English as an additional language at age seven have slightly lower attainment levels than pupils with English as their first language. However, this difference no longer exists by age 16. Analysis has also shown that there is no evidence of a relationship between the proportion of pupils with English as an additional language and the overall level of pupil attainment[11].

GCSE results were broadly consistent between 2016 and 2019, with around 70% of pupils achieving grade 4/C or above in England and a quarter of students achieved a grade 7/A or above in 2020. In Scotland the pass rate for the equivalent National 5 exams was 78% in 2019. However, the impact of disruption to teaching for long periods of time throughout the Covid-19 pandemic on educational attainment, skills and learning have been significant. There were 728,000 young people aged between 16 and 24 years not in education, employment or training (NEET) in the UK for the period January to March 2021. Surprisingly this was a record low of 10.6%, and down compared to pre-pandemic estimates from October to December 2019[12].

Health and well-being

The National Child Measurement Programme takes place in England each year. It measures the height and weight of children in reception (age 4-5) and year six (age 10-11). For the 2019-20 school year it found that the levels of obesity in reception had increased to 10% and for year 6 the figure was 21%. The rates of obesity varied by age, sex, ethnicity, geography, religion and deprivation. Boys had higher levels of obesity than girls for both age groups. Children living in the most deprived areas were more than twice as likely to be obese than those living in the least deprived areas[13]. The 2018/19 Child Measurement Programme for Wales found that 72% of children were a healthy weight, but that there was significant variation across local authority areas and again by deprivation levels[14]. Obesity rates in Scotland are higher than the overall UK average. Obesity Action Scotland estimated that in 2018, 30% of children aged between 2 and 15 were at risk of being overweight or obese[15].

A paper published in the British Medical Journal[16] examined the short and long term consequences of exposure to adversity in childhood. It found growing evidence that biological (malnutrition, infectious disease) and psychosocial (maltreatment, extreme poverty) experienced in the first three years of life can have an impact on a child’s development, leading to an increased risk of physical and mental health conditions, which can continue into adult life. A 2017 survey of children and young people's mental health found that 12.8% of children between 5 and 19 years had at least one mental health condition. Children whose households were receiving low-income benefits were almost twice as likely to have a mental health condition (18.2%) compared those who were not (9.8%)[17]. When taken together with the figure quoted by the Mental Health Taskforce, that half of all mental health illnesses are established by the age of 14 and 75% by age 24[18], it presents a concerning future for many young people.

A comprehensive data set from Public Health England[19] brings together a range of publicly available data, information, reports, tools and resources on child and maternal health into an accessible hub. It can be searched by local authority or region, and covers factors including school readiness, traffic injuries, obesity levels and homelessness. Public Health Scotland, Public Health Wales, Public Health Agency in Northern Ireland and Department for Public Health in Ireland all collate similar information.

Poverty

Large numbers of children live in poverty in the UK and Ireland. 4.2 million children were living in poverty in England in 2018/19 an increase of 600,000 since 2012[20]. Around 28% of children in Wales live in poverty. The Northern Ireland Commissioner for Children and Young People (NICCY) estimated that 103,400 children in Northern Ireland were living in poverty, almost one in four of all children in 2017[21]. The Central Statistics Office reported that approximately 100,000 children (8.1%) in Ireland were living in consistent poverty in 2020[22].

The Social Mobility Commission have projected that the number of children living in poverty will increase markedly as a result of Covid-19. The Commission reported that almost three-quarters of children living in poverty are in households where at least one adult is in work. The impact of living in poverty is felt throughout a child’s life. Only 57% of pupils entitled to free school meals have achieved a good level of development when starting school, compared with 74% of all other pupils. Whilst at 16, only a quarter of disadvantaged students get a good pass in English and Maths GCSE, compared half of all other pupils[23].

Children from ethnic minority communities are more likely to live in poverty. Around one-quarter of children in households in an Asian ethnic group and one in five children in Black households live in persistent poverty, compared to one in ten white British households. Poverty is a source of stress for children. The Children’s Commissioner for England[24] reported that 21% of children list ‘not having enough money’ as one of their top three worries. Evidence indicates that with around one-quarter of children with Asian heritage and one in five children with Black African/Caribbean heritage living in persistent poverty, compared to one in ten white British households child poverty is particular issue for families from a Black or Asian community.

The health risks to children living in poverty are starkly demonstrated in research by the University of Bristol’s National Child Mortality Database[25]. The research analysed the records of 3,347 children who died in England between April 2019 and March 2020. The researchers correlated the child’s residential address to the Government’s measures of deprivation index, which uses data on income, employment, education, health, crime, access to housing and services, and living environment to calculate a deprivation score. They found that for each point increase in deprivation, there was a 10% increase in the risk of death. Almost three times as many deaths occurred in the most deprived decile, compared with the least deprived. Housing problems, including cleanliness, overcrowding, or maintenance (damp or mould) were identified in 123 of the deaths reviewed.

Travel and independence

Between 2015 to 2019, the average journey to school in England, Scotland and Wales was 19 minutes (one way), with the average distance being 2.4 miles based on the National Travel Survey. Walking was the most common form of transport for all groups at 44%, followed by car at 35%[26].

Over time the distance that children in the UK travel from home independently has decreased. In 1971, 94% of children aged 7-11 years in England were allowed to go out alone. By 2010 that had shrunk to 33%. This downward trend has been observed in many European countries, however countries including Finland, Germany, Norway, Sweden and Denmark all still have higher levels of independence. In Finland in 2011, for example, 87% of children aged 7-11 were allowed to go out by themselves[27]. There are differences between genders in terms of the amount of independent mobility they are allowed, with girls typically being less likely to be independent and at a later age[28].

Play

The same definition of play has been adopted by all the national play organisations[29] in the UK. It defines play as ‘a process that is freely chosen, personally directed and intrinsically motivated. That is, children and young people determine and control the content and intent of their play, by following their own instincts, ideas and interests, in their own way for their own reasons’. All children and young people need to play. It is a biological, psychological and social necessity and is fundamental to the healthy development and well-being of individuals and communities. Laura Walsh, Head of Therapeutic Play Services at Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children NHS Foundation Trust describes play as a “fundamental part of childhood and is essential to children’s well-being, growth and emotional development”[30].

Children’s opportunities for play have reduced over time. This is due to factors including, less breaks during the school day, increased amounts of homework, more after school activities and risk averse parenting styles[31]. There has also been an increase in levels of screen time, with 93% of 7-11 year old’s spending 13.5 hours a week online[32]. The increase in screen time causes a great deal of concern for parents. It also results in children leading much more sedentary lifestyles and again limits the time available for independent outdoor play. These trends are compounded by parents safety concerns of playing outside in the street because of traffic levels and fear of crime[33]. A study by the National Trust from 2012 found that children play outside for an average of four hours a week, compared to an average of eight hours when their parents were children[34].

Covid-19

An article published in The Lancet[35] in March 2021 on the impact of Covid-19 on children concluded that children and young people remain at low risk of COVID-19 mortality. Children have not become seriously unwell with COVID-19 and have not required hospital treatment in large numbers.

However, children have been severely affected by the restrictions on movement, closure of playgrounds and recreational areas, ability to meet family and friends and the impact on education and development from the closure of schools and nurseries for long periods of time. They have also been affected by the economic impact of lockdowns. A study, undertaken by the NHS in July 2020, found that clinically significant mental health conditions amongst children had risen by 50% compared to three years earlier. The Children’s Commissioner for England has noted that the long-term consequences of the increase in children’s mental conditions health are not yet fully known[36].

The pandemic has led to an increase in the number of children living in poverty, with many families losing income. The England Children’s Commissioner estimated that 88,000 children had seen a parent lose their job by April 2020, 1.2 million children were in families where a parent had been furloughed, and 2 million children were in families where a parent’s working hours had been reduced[37]. High profile campaigns for the provision of free school meals during school holidays have highlighted the extent of the poverty many children live in.

Educational catch-up programmes have been developed by governments in the UK, Ireland and internationally. They aim to mitigate against the disparities in educational attainment exacerbated by home learning. However, several charities, including Save the Children, NSPCC and the Lego Foundation, along with each of the national play charities have launched the Summer of Play[38] campaign. It aims to give children the space, time, and freedom to play during summer 2021. The importance of play during the Covid-19 pandemic have been highlighted in a report by Great Ormond Street Hospital Children’s Charity[39]. The charity surveyed 2,543 parents of children aged between five and eleven years old, from across the UK. It reported that 74% of parents found that play ‘helped their child cope’, with two-thirds voicing concerns about the long-term impact of the pandemic on their child’s well-being.

3. Built environment and children

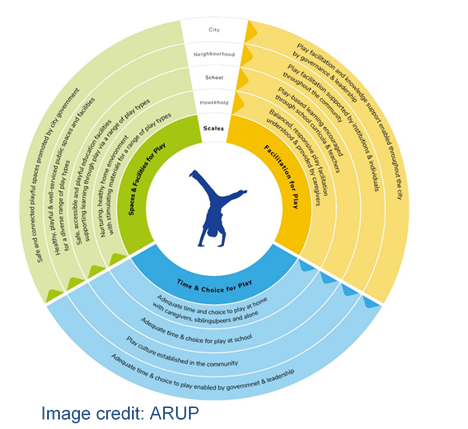

When considering the needs of children, town planning has traditionally focused on the provision of schools and sports and recreation facilities. In recent years several children’s play advocates, from outside the planning profession have focused attention on the role of the built environment on providing the conditions to facilitate play. However, for the planning profession to properly address the impact of the built environment on children, a more holistic approach needs to be taken, covering all aspects of children and young people’s lives. Tim Gill[40], a longstanding advocate for child-friendly urban planning and design says that “children can be seen as an indicator species for cities. The visible presence of children and youth is a sign of the health of human habitats.” In this way a place that works for children can be seen to work for everyone.

The focus on children and the built environment was strengthened by the Children’s Commissioner for England’s call for child-friendly planning in their Mean Streets[41] report published in 2020. It recommends that planning guidance should specifically include children’s need for ‘safe open spaces and play opportunities’, and for local authorities to be required to consult with children.

This chapter will examine some of the ways that the built and natural environment can have an impact on the health and well-being of children and young people.

Food environments

According to a survey taken in 2017/18 around 50% of local plans contain policies that restrict the location of takeaways. Many of these policies are ‘exclusion zones’ for planning permission for hot food take-aways within walking distance of schools (around 400 metres). Whilst limiting the unhealthy food options available to children is certainly part of the solution to tackling rising levels of obesity, it needs to be part of a broader approach that also promotes the ability to make positive healthy lifestyle options and tackles low activity levels. Public Health England’s guidance, ‘Using the planning system to promote healthy weight environments’[42], published in 2020, has a focus on children and includes the role of schools in fostering a healthy lifestyle from an early age. Importantly the guidance takes a more holistic approach than seen in the past and recommends that local planning authorities produce supplementary planning guidance that covers not only the location of hot food take-aways, but also active travel, open space and public realm. It also emphasises the need coordination between planners and public health professionals.

School environments

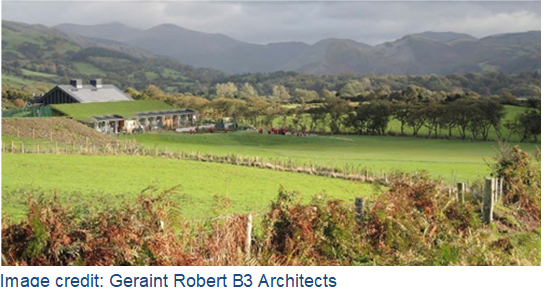

The quality of the school environment can have an impact on children’s well-being, concentration levels and ability to learn. Positive design factors include, space, lighting, air quality, temperature, and acoustics. Age-appropriate and flexible learning spaces that can be adapted to different teaching styles, along with connections (entrances and corridors) that are easy to navigate and move through are also essential factors. A school is also a community, so a school that is attractive and adapted for the people who study and work there creates a sense of ownership and pride. A report by the World Bank estimates the impact of the quality of the school environment on pupils learning is a variable of around 16%[43]. The report also recommends that school infrastructure projects should also engage with a range of stakeholders to maximise the potential in terms of learning outcomes. School infrastructure projects that engage with local communities and potential pupils in their design are more successful. See the case study for Ysgol Craig Y Deryn in chapter 7 along with Hugh Baird College and the Struan Centre for Autism in the RTPI practice advice on ‘Mental health and town planning’[44] for examples of where this approach has been used.

The quality of the outdoor space at schools has gained more prominence, beyond the provision of space for sports and a playground, to an expansion of the learning environment. School buildings and outside space are high quality, local resources. Opening up their use to the community outside of school hours does present issues of maintenance, security and liability, but they can offer improved access to outdoor space for children in both urban and rural communities[45]. There is also an improved recognition of the importance of greenspace in schools. In some cases, planting is used as a barrier to pollution in built up areas.

Housing

Research published by the National Housing Federation[46] found that more than 10% of children in England were living in overcrowded housing in 2019, around 1.3 million children. Overcrowding is often due to a lack of affordable housing. The Office for National Statistics records that since 1997 housing affordability has worsened, most notably in London, and is largely driven by increasing house prices[47]. This is against a backdrop where in England, 20% of homes currently fail to meet the Decent Homes Standard. In the private rental sector, this figure rises to 25%. This Standard requires houses to meet the statutory minimum standards of a reasonable state of repair and to have reasonably modern facilities and services and thermal comfort. In 2017, 48% of houses in the private rented sector failed to meet the Scottish Housing Quality Standard. In Wales 24% of private rented housing had one or more category one hazards (according to the Housing Health and Safety Rating System). The situation is much more positive in Northern Ireland, with 11% of private rented housing failing to meet the Decent Homes Standard in 2016. For children growing up in these homes there are potentially long-term impacts on their health, well-being and education.

Added to this situation are the results of a survey by Shelter[48] and YouGov that highlighted 136,000 children were living in temporary accommodation across Britain in 2020. Issues including missing school, hunger, dirty clothing and tiredness were reported by their teachers, all of which contribute to a child’s ability to learn and enjoy school.

The location of housing and the ability to access everyday services, including school, play and sports areas and local shops via active travel methods is also a consideration in creating child-friendly places. Building housing in sustainable locations can promote gradual independence for children as they can complete local trips alone or with friends. The RTPI has carried out extensive research on the location of development across England[49]. The next iteration of the research will examine the average distances to nine different services, including schools and town centres.

Mobility

Child-friendly places should allow children to enjoy everyday freedoms and mobility is an important part of this freedom. As children grow their horizons expand and they gain independence from their parents and caregivers. At its most successful this journey is gradual and smooth[50]. However, due to safety fears and the reliance on cars for transport, issues which are often compounded by the built environment form, this gradual increase in independence often does not take place. Town planners can work proactively with their transport planning and highways colleagues to reduce the dominance of cars in terms of both road layout and parking in developments in order to make neighbourhoods more child-friendly. There are examples of where this has been achieved, for example in the Marmalade Lane co-housing development, where car parking is restricted to the edge of the site as outlined in chapter 6.

One way of increasing the choice and mobility of children and young people can be through implementing the principles of the 15-minute city (also known as the 20-minute neighbourhood). Whilst not a new concept, it has gained prominence because of the focus on local areas due to the impact of restrictions on movement imposed in response to the Covid-19 pandemic. The basic concept is a model of urban development that creates neighbourhoods where daily services can be accessed within a 15–20 minute walk. In Scotland, 20-minute neighbourhoods have been included in the Programme for Government 2020-21[51] and in the National Planning Framework 4 Position Statement[52]. The aim of 20-minute neighbourhoods is to regenerate urban centres, enhance social cohesion, improve health outcomes, and support the move towards net-zero carbon targets, through reducing unsustainable travel[53]. Several interventions need to be considered to support the implementation of a 20-minute neighbourhood. These include active travel, public realm and greenspace enhancements, traffic reduction, service provision and densification. All these interventions can and should have a child-friendly approach embedded within them.

A related policy intervention is low-traffic neighbourhoods (LTN’s). These are residential areas, where through motor vehicle traffic is discouraged. Again, this is not a new policy concept, but they have gained prominence, and controversy, during the Covid-19 pandemic. In Glasgow, the decrease in traffic during Covid-19 restrictions has been used to experiment with the introduction of the first LTN in the neighbourhood of Dennistoun[54]. Orford Road in Walthamstow Village, London is an established LTN. Whilst not specifically designed as a child-friendly project, the benefits of becoming a pedestrian friendly place are felt by children and adults alike. It is discussed in the RTPI Mental health and town planning practice advice[55]. Both policy approaches fit within the sustainable location of development that is at the heart of planning in the UK.

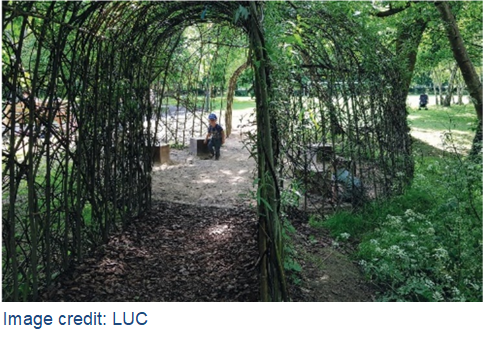

When considering the needs of children, the emphasis is on the destination. However, it is also important to consider the journey, providing safe and accessible routes. Incidental play and exploration can be incorporated in everyday journeys, through tactile surfaces and this has been incorporated in the London Borough of Hackney’s supplementary planning advice for children, as the principle of ‘Play on the way’. See chapter 6 for more details.

Public realm

High quality, well considered and inclusive urban design can play a significant role in making places more child-friendly. The public realm can be designed to relate to buildings in a way that is welcoming to children, offering safe opportunities to move, gather and play. To facilitate this, developments should be built with ample shared, car-free outside space with direct, or easy access from adjacent homes, with clear lines of sight for natural surveillance. The quality of the connecting spaces, the road crossings and footpaths are also important, as is the orientation of homes, with traditional street arrangements where front doors face others fostering social interaction[56].

The ongoing management and maintenance of streets and public space is also important. Places that are well maintained promote confidence in children and their parents that they are safe and suitable places for them to be. If the long-term management of public spaces, including responsibility for maintenance and funding is considered at the design and building stage it helps to ensure that they are sustainable over time[57].

Greenspace and recreation areas

The link between green space and well-being is well established. Studies have shown that people experience less mental distress, less anxiety and depression, better well-being, and healthier cortisol levels (the hormone that controls mood) when living in urban areas with more green space compared to less[58]. The impact on spending time in greenspace is particularly important for children as it provides opportunities and space to play and experience the natural world. The positive impacts of quality greenspace for children includes the ability to cope with life stresses, concentration, activity levels and social skills[59].

However, almost 2.7 million people in the UK also do not have a publicly accessible local park or green space within a ten minute walk of their home. The ability to access greenspace is being further constrained with the loss of school playing fields. 250 school playing fields were disposed of between 2010 and 2021 in England[60] for a variety of reasons. Fields in Trust campaign for equitable access to greenspace to help create happier, healthier communities. They have developed a searchable Green Space Index[61] that identifies publicly accessible park and green space provision across, England, Scotland and Wales. Fields in Trust are also responsible for the six-acre standard that recommendations that 6 acres of accessible green space per 1,000 head of population is available to enable residents to participate in sport and play[62]. A survey in 2014 estimates that 75% of local authorities adopt this or an equivalent standard.

Air quality

Air quality is a concern in the UK, and the impact of breathing polluted air is particularly damaging for children, as it can harm the normal growth of lung function during pregnancy up until late teens. It also increases the risk of sensitisation, which can lead to asthma and other respiratory conditions. Children are particularly vulnerable to traffic pollution because their height means they are closer to exhaust fumes. The high number of people who drive their children to school means there is a concentration of traffic and pollution where large numbers of children congregate.

Children are concerned about the levels of pollution near their schools. A survey commissioned by the walking and cycling charity Sustrans found that around half of UK school pupils are worried about air pollution. With 40% of pupils agreeing that more people walking, cycling or scooting to school was the best way to bring down air pollution near their school[63].

The introduction of school streets is one initiative to tackle this issue. They are most common in urban areas, and whilst their introduction can be controversial with residents and parents, they are showing positive results. School streets are being delivered as part of the London Mayor's Streetspace for London plan. A study measured the impact of school streets at 18 primary schools across London to record nitrogen dioxide levels. It found that closing the roads around schools to traffic at pick-up and drop-off times reduced polluting nitrogen dioxide levels by up to 23% and is strongly supported by parents[64].

Equality, diversity and inclusion

The basic qualities of what makes a place child-friendly are the same for a child of any age[65], which has been outlined as a simple set of principles in chapter 5. However, in more detailed terms there are many factors that need to be considered to ensure that places are inclusive and designed to meet the different needs of children in terms of their age, disability, sex, race, religion or belief.

The charity Make Space for Girls[66] argues that whilst there is little in the way of consideration of children in the design of places, there is even less consideration of the needs of teenage girls. The charity argues that a more equitable approach needs to be taken as playgrounds are mainly designed for younger children and skate parks and multi-use games areas (MUGAs) are predominantly used by teenage boys, leaving teenage girls with few options of outdoor places where they can congregate and feel safe and comfortable. This is backed up by the results of a survey by Girlguiding[67] that found girls and young women face specific barriers which stops them accessing outdoor spaces and local facilities. The survey found that 82% of respondents thought that they should be more involved in designing playgrounds, parks and outdoor facilities.

Disabled children and young people are particularly restricted by the built environment. From pavements, seating, entrances, and play areas, much of the public realm is not designed for disabled access. Going beyond disabled access regulations to deliver places that work for disabled children would represent real inclusion.

Child’s view of the world

Parents, professionals and politicians all have strong views about what is best for children. However, this is from an adult’s perspective, and they may not identify the same issues as the children themselves. Therefore, it is vital to consult and engage with children and young people in a meaningful way about the places they live, visit, study and play. A wide range of creative and engaging techniques have been developed to do this effectively. The case studies in chapter 6 and the engagement tools in chapter 8 outline some of the ways this can be carried out and the benefits of doing so. Children have valuable insights to make, and they care about the environment, as evidenced by the large number of student led climate change groups in schools in the UK. There are also links to the school curriculum on climate change and the built environment across all key stages.

One issue around engagement with children on changes to the built environment is the long time that elapses between initial engagement and projects being built out. Catherine Greig of make:good[68], an architecture and design studio that specialises in engaging with children and young people in shaping neighbourhood change recommends that immediate, meanwhile uses are incorporated into development and regeneration schemes so that children can see a tangible result of their involvement in the short term as well as influencing the longer term change.

The Children’s Commissioner for England report on teenager’s safety, harassment and fear of crime[69] highlighted pervasive fears about going out in public. It highlights the negative presentation of teenagers, which can lead to design solutions that prevents them from congregating and socialising. The report goes on to say, “One mark of a child-friendly society is surely whether children feel safe and confident to play outdoors and enjoy public spaces independently.”

4. Legislation and policy

The RTPI commissioned a review of ‘Child-friendly planning in the UK[70]’ in 2019. It examined national planning policies and found that ‘children are currently most visible through their absence’. Changes to the UK and Irish planning systems are ongoing. This chapter outlines how the current planning systems relate to children and how recent national policy consultations create an opportunity for more child-friendly town planning. For a fuller discussion of national planning policy in relation to children see our review.

Equalities legislation

Age is one of the nine protected characteristics of the Equality Act 2010[71] that applies to England, Scotland and Wales. The other protected characteristics are disability, gender reassignment, marriage and civil partnership, pregnancy and maternity, race, religion or belief, sex and sexual orientation. As children and young people can also embody these characteristics, sensitivity is needed to ensure all their needs are met. The accompanying Public Sector Equality Duty[72] requires public authorities to eliminate discrimination, to advance equality of opportunity and foster good relations between persons, in public sector decision-making at every level, therefore providing protection to children. In Northern Ireland, Section 75 of the Northern Ireland Act 1998 places a statutory duty to consider the potential impact of decision making on protected groups, including age. The Equality Commission for Northern Ireland[73] has links to the relevant equalities’ legislation. The Irish Human Rights and Equality Commission enforces the Public Sector Equality and Human Rights Duty under the Irish Human Rights and Equality Act 2014[74].

UN Convention on the Rights of the Child

The UK and Ireland signed up to the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC)[75] in 1992. The Convention is an international human rights treaty that grants all children (aged under 18) a comprehensive set of rights. As signatories, the UK and Ireland have a responsibility to implement the Convention’s articles and report on progress towards achieving them. The UK last reported in December 2020[76] and it includes information on the impact of Covid-19. However, despite the recommendations of the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child the Convention is not incorporated into legislation in all parts of the UK.

In 2021, the Scottish Parliament voted to incorporate the Convention into Scottish Law[77]. The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (Incorporation) (Scotland) Bill also contains proactive measures in addition to the Convention. These include an obligation on the Scottish Government to conduct a Child Rights Impact Assessment on every new policy and legislation that affects children to ensure that children’s rights are respected when considering new policy and fiscal decisions. In Wales there has been a requirement for Ministers to have due regard to the UNCRC since 2014[78]. However, this does not give the Convention the same status as national policy.

Each UK nation has a separate Children’s Commissioner. In Ireland there is an Ombudsman for Children. Their roles are to safeguard and promote the rights and best interests of children and young people as set out in the UNCRC.

England

The National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF)[79] contains only one mention of children. This is in relation to delivering a sufficient supply of homes, for families with children. In relation to schools the NPPF focuses on providing a sufficient supply and choice of school places to meet the needs of existing and new communities, and the siting of telecoms masts near schools. However, whilst it does not make specific reference to children, Section 8: Promoting Healthy and Safe Communities, states that planning policies and decisions should, ‘enable and support healthy lifestyles, especially where this would address identified local health and well-being needs’. The Framework also acknowledges that access to a network of high-quality open spaces and opportunities for sport and physical activity is important for the health and well-being of communities (para 96).

The National Planning Practice Guidance (NPPG) supports the NPPF. There is very limited guidance that is specific to children. It covers the provision of school places, the allocation of land for education and the health of the food environment, particularly where children congregate. Whilst the NPPG covers open space and sports and recreation provision, again it has no direct mention of children. The broad definition of infrastructure means that Community Infrastructure levy (CIL) and Section 106 contributions can be used to fund the development of facilities such as play areas, open spaces, parks and green spaces, cultural and sports facilities, but not their maintenance.

Neighbourhood plans could provide an opportunity to introduce child-friendly policies at a local level. However, as neighbourhood plans should support the delivery of strategic policies set out in the local plan, the same policy and guidance context of the NPPF and NPPG applies.

Planning for the Future: White Paper[80] was published for consultation in 2020 by the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (MHCLG). It did not mention child-friendly places in its ambitions for the future.

The Play Strategy[81] set out a vision for play in England and operated between 2008 and 2011. Whilst there is no longer a play strategy for the rest of the country, local planning authorities in London must adhere to the London Plan, 2021 that includes the requirement for development plans to be informed by a needs assessment of children and young person’s play and informal recreation facilities, including an audit of existing provision and a play strategy[82]. See the case study in chapter 6 for more details.

As part of the Uniting the Movement[83] campaign, Sport England have identified five ‘big issues’ to help England recover from the Covid-19 pandemic. These include positive experiences for children and young people, along with focusing on creating active environments and how the wider built environment influences how much people move. It identifies that good design can help to increase activity levels by encouraging walking and cycling.

Wales

Planning Policy Wales: Edition 11 was published in 2021[84]. It sets out the land use planning policies of the Welsh Government. There is very little direct mention of children. In the section on active and social streets (4.1.19) it highlights streets importance as somewhere children can play. The benefits of high-quality green space and recreational spaces to the health and well-being of children is also stated (4.5.1).

Future Wales: the national plan 2040[85] was also published in 2021. It is the development plan for Wales and influences all levels of the planning system in Wales. There is also a helpful young person’s summary of the plan to assist with engagement. However, it says little of direct reference to children beyond the need to, ‘provide opportunities to support children and young people and promote active lifestyles’.

Technical Advice Note 16: Sport, Recreation and Open Space (TAN16)[86] published in 2009 highlights ‘the critical importance of play for the development of children’s physical, social, mental, emotional and creative skills.’ This is supported by benchmark standard recommendations for outdoor play in terms of type (doorstep, local, neighbourhood) size (hectares) and distance (walking) from homes. TAN16 also makes a distinction between formal and informal play. Highlighting the benefits of informal ‘playable spaces that can provide opportunities for children to interact and gain the social, health and well-being benefits which come from opportunities for active, physical play.’ TAN 16 strongly supports the value of engaging children and young people in the planning process. It states, ‘involving children and young people in planning provision is essential …. Local planning authorities should seek to involve them from the outset, when preparing development plans, design briefs, supplementary planning guidance, and local play strategies.’ It also makes links to the support available from Play Wales[87], therefore providing a coordinated response.

Planning policy in Wales is built on the strong foundations of the Well-being of Future Generations (Wales) Act 2015[88]. The Act requires public bodies to make sure that they take account of the impact they could have on people living in Wales in the future. An inclusive approach to achieving the well-being goals is strongly encouraged, including the involvement of children and young people, which is supported by the National Participation Standards for Children and Young People[89]. The Standards place a requirement on local authorities to undertake all reasonable measures to ensure that children and young people are involved in the planning, implementation, and review of decision-making processes. It stresses that children’s participation is an ongoing process rather than simply a series of one-off engagement events.

Wales was the first country in the world to legislate for play with the introduction of the Play Sufficiency Duty[90] in 2010. It is part of the Welsh Government's anti-poverty agenda. It places a duty on local authorities to secure sufficient play opportunities for children. The Duty requires local authorities to produce a Play Sufficiency Assessment every three years. The assessments take account of demographic profiles, along with an assessment of play and recreational provision. It also considers other factors that promote play opportunities, including planning and transport.

The design guidance that accompanies the Active Travel (Wales) Act 2013[91] includes an emphasis on encouraging active travel by children and young people. The needs of children and young people are considered throughout the document, from cycling, pavement width around schools to seating. It states that well designed active travel infrastructure can support the aims of the Rights of Children and Young Persons (Wales) Measure 2011. The consideration of the needs of children were strengthened in the updated 2020 consultation version[92] of the guidance.

Scotland

The Planning (Scotland) Act 2019[93], states that one of the purposes of planning is to achieve the national outcomes identified in the National Performance Framework[94]. The outcomes include a Scotland where people ‘grow up loved, safe and respected so that they realise their full potential’. It goes on to outline a vision where, ‘Our communities are safe places where children are valued, nurtured and treated with kindness. We provide stimulating activities and encourage children to engage positively with the built and natural environment and to play their part in its care’.

The Planning Act also includes the provision, ‘a planning authority must make such arrangements as they consider appropriate to promote and facilitate participation by children and young people … in the preparation of the local development plan.’ Local planning authorities are also required to carry out play sufficiency assessments, in a similar approach to that taken in Wales. The legislation changes will be reflected in the National Planning Framework 4 (NPF4) which will be adopted in 2022.

Designing Streets: A Policy Statement for Scotland was published in 2010[95], it sets out guidance on street design and was the first Scottish planning document to contain a change in emphasis away from motor vehicles to promote streets as social spaces, ‘where children can play’.

Play Scotland published a Play Strategy[96] in 2013. It has the vision for Scotland to be the ‘best place to grow up. A nation which values play as a life-enhancing daily experience for all our children and young people: in their homes, nurseries, schools and communities.’ It recognises the role of the planning system in delivering opportunities for play. The 2021 progress review made eight recommendations on how Scotland’s Play Strategy should be taken forward in the light of COVID-19. These include, renewing and developing the national and local commitment to outdoor play, and listening to children and young people and act on what they say.

Northern Ireland

The Regional Development Strategy 2035[97] was published in 2010, it provides an overarching strategic planning framework to facilitate and guide the public and private sectors. One of the aims of the strategy is to ‘promote development which improves the health and well-being of communities’. However, there is no direct reference to children in the strategy.

The Strategic Planning Policy Statement for Northern Ireland (SPPS)[98], published in 2015, sets out the Department for Infrastructure’s regional planning policies. It is based around five core planning principles. These include improving health and well-being, creating and enhancing shared space and supporting good design and positive place making. The only references to children are in relation to the accessibility of open space, sport and outdoor recreation.

The Planning Policy Statements that predate the SPPS are retained under transitional arrangements. Planning Policy Statement 8: Open Space, Sport and Outdoor Recreation[99] talks about the particular importance of accessibility to open space by children. Stating that open space is, ‘an essential element in the development of all children’. It includes open space requirements for new build developments. Stating that for residential developments of more than 100 units there should be an equipped children’s play area within a reasonable walking distance of the majority of homes.

Northern Ireland published a strategy for children and young people called ‘Our children and young people our pledge 2006 to 2016’[100] in 2006. It identifies that not all children have an equal start in life, and it aims to improve the well-being of all children in Northern Ireland. A consultation on an updated strategy took place in 2016, however it has not yet been published. The draft strategy highlights the ‘diminishing nature of childhood play experiences, identifying that whilst play is considered important by children and young people of all ages, a lack of accessible play spaces within communities often reduces opportunities for outdoor play.’[101]

Ireland

Project Ireland 2040: National Planning Framework[102] was published 2018 to guide development and investment. It outlines 75 National Policy Objectives (NPO). The only direct mention of children is in relation to investment in childcare, schools and higher education (NPO 31). The National Planning Framework is accompanied by a ten-year investment plan. The investment focus in terms of children is on a school building programme, with further investment in childcare provision.

Better Outcomes, Brighter Futures: The National Policy Framework for Children and Young People, 2014-2020[103] aligns government commitments to children and young people against five national outcomes, including health, achieving potential, safety and connected. These outcomes are for all government departments, agencies and voluntary sector to work towards. It emphasises an integrated and evidence-based approach to working and is informed by consultation with children and young people. In the Framework the Government committed to, ‘Develop child- and youth-friendly communities through Local Government adopting appropriate policies and objectives in County/City Development Plans and further supported by the preparation and issuing of National Guidelines on Planning for Child-friendly Communities’, which so far have not been published.

5. What does a place designed for children look like?

As outlined in chapter 3, the quality of the built environment and access to nature can have a significant impact on the quality of children’s lives. Whilst town planners need to work within the current legislative and policy context there are a set of design principles that should be considered when creating child-friendly places. These can be applied to many settings - urban or rural, new development or existing settlement.

|

Welcoming – places are designed to help children develop a sense of belonging. There are a variety of cues to indicate they are welcome, including signage, design and layout. There are opportunities to socialise through play and gathering. |

|

|

Local – everyday services (schools, shops, play areas etc.) are located safe, walkable, distances from homes. The principles of the 15-minute city/20-minute neighbourhood[104] apply. Having local access to services fosters independence of movement as children grow. |

|

|

Engaging – children and young people are involved in the design of the places where they live, travel and visit. Their needs have been met because they have been consulted. |

|

|

Sustainable – places are built using the principles of sustainable development, they are high quality, adaptable and built to last. They engage and promote children and young people’s understanding sustainable design. They are built to adapt to and mitigate against climate change[105]. |

|

|

Play – places are designed with a variety of opportunities for play. At home with the provision of outside space, as part of a journey as an integrated part of neighbourhood design and in designated play areas. Play space is provided at a variety of scales and suitable for a range of ages and activities. The design of play spaces is fun, imaginative and responds to the local context. |

|

|

Green – children and young people have free access to greenspace and nature near their homes. It is provided at a variety of scales, from doorstep greenspace through street trees, to pocket parks and play areas and sports fields. There is a mixture of managed and natural spaces. |

|

|

Inclusive – places are designed to cater for diverse communities. They are built to accommodate the needs of children terms of their age, gender, ethnicity, ability, income and culture etc. There are opportunities for intergenerational interaction. Spaces are flexible and multi-use and can be used for play, socialising, rest, learning, and other activities. |

|

|

Confidence – places are designed to give children and young people (and their parents and guardians) the confidence to use them. They have natural surveillance, are well maintained and risk assessed. Housing provision is affordable and well located. Traffic is minimised and there are safe walking and cycling routes. |

|

6. Planning for children

There are many opportunities for town planners to positively plan for the needs of children and young people within their work. Their needs will be met more effectively by the built environment if they are fully integrated at an early stage within policies, plans and developments, rather than being seen as an add on at a late stage in the planning process.

With the use of a series of case studies, this chapter will highlight how places can be successfully designed to be more child-friendly in a variety of ways. The approaches outlined in the case studies are supported by academic research into children and the built environment[106]. They are:

- Engage with young people at the scoping stage;

- Include child-friendly policies in plans;

- Publish supplementary planning advice on children;

- Use child-friendly programmes to initiate action;

- Create welcoming city centre spaces for children;

- Take innovative approaches to developing child-friendly developments.

Case study: Engage with young people at the scoping stage – Liverpool City Region Combined Authority

The Liverpool City Region’s Spatial Development Strategy[107] (SDS) is a statutory planning document that will form part of the development plan for the city region’s six local authorities, alongside their own local and neighbourhood plans. Combined authorities are only required to consult once, at the end of the process when developing their strategy. However, this approach did not fit with the ‘no neighbourhood left behind’ ethos of the Liverpool City Region (LCR)[108]. Therefore, there has been extensive engagement throughout.

A significant aspect of the engagement process has been to understand the views of people who do not normally engage in the planning process, in particular young people aged under 25. The approach was supported by the leaders of all six local authorities. A range of activities and have been undertaken. The spatial planning team designed and co-ordinated the engagement work. However, understanding and learning have developed throughout the engagement process.

LCR worked with the social enterprise, PLACED[109] who specialise in working with groups who do not usually engage in the planning process. They ran 13 town centre engagement days engaging with 350 people. These interactive events took place in vacant retail units to ensure that it could attract a high footfall of local people The vast majority of those who attended would not have considered engaging if it wasn't for these drop in venues. Some young people who had engaged in the event became advocates, encouraging others to join in. PLACED also ran a four-day Academy for 14-17 year olds. It began by asking the young people what they want from where they live. It focused on ideas, rather than policies.

LCR worked with the social enterprise, PLACED[109] who specialise in working with groups who do not usually engage in the planning process. They ran 13 town centre engagement days engaging with 350 people. These interactive events took place in vacant retail units to ensure that it could attract a high footfall of local people The vast majority of those who attended would not have considered engaging if it wasn't for these drop in venues. Some young people who had engaged in the event became advocates, encouraging others to join in. PLACED also ran a four-day Academy for 14-17 year olds. It began by asking the young people what they want from where they live. It focused on ideas, rather than policies.

Sefton Young Advocates facilitated a workshop with their network of young people aged 13–24 years old, using KETSO, the specialist engagement tool. Working with specialist engagement teams has been an investment for LCR, but it has ensured a bespoke approach and it has led to more in depth and better engagement.

Students are a cohort of young people that it is particularly difficult to engage with, as they often leave the city before development takes place. To reach this group, good relationships with the Department of Civic Design, at the University of Liverpool were utilised and a workshop took place for 49 students. It formed an element of the University’s Planning degree. Younger members of the strategic planning team led engagement events. Participants were able to relate to them better and it created a less challenging environment, encouraging quieter members of the group to speak.

The engagement identified climate change and the environment as the most important issue to the LCR community with 37%, followed by health and addressing health inequalities. For LCR this demonstrates the importance of wider inclusive engagement as it helped to identify policy areas that may not have been prioritised by more typical engagement.

Following the first engagement stage the spatial planning team reviewed the responses and created a ‘You said We did’ background document, which was used to shape a second stage. The results of stage two are also publicly available[110]. This open access feedback loop is important as it demonstrates to participants that they have been listened to. By placing the results online, they can be used by a range of stakeholders, including developers.

Mark Dickens, Lead Officer for Spatial Planning at LCR views the engagement process with younger people positively saying, “Younger people are less protective of what they have. They are not looking to maintain the status quo. It’s been a breath of fresh air.”

Case study: Include child-friendly policies in plans – The London Plan 2021

The London Plan[111] was published in 2021. It is the spatial development strategy for Greater London for the next 20-25 years. The plan has a focus on ‘Good Growth’, by which it means growth that is socially and economically inclusive and environmentally sustainable. The London Plan forms part of the local plan of each of the 32 London boroughs. It must be taken into account when planning decisions are taken in any part of Greater London.

The London Plan[111] was published in 2021. It is the spatial development strategy for Greater London for the next 20-25 years. The plan has a focus on ‘Good Growth’, by which it means growth that is socially and economically inclusive and environmentally sustainable. The London Plan forms part of the local plan of each of the 32 London boroughs. It must be taken into account when planning decisions are taken in any part of Greater London.

This is a detailed document, at over 500 pages and it is important to note that the references to children, whilst concentrated on education, childcare; and play and recreation continue across the breadth of the document. The impact on children and young people are also covered in policies on the economy, inclusion and diversity, provision of public toilets, healthy food environment, air quality, cycle parking and mobility, reflecting a holistic approach.

In terms of the design of education and childcare facilities the policy goes beyond the provision of sufficient school places. It states that, ‘education and childcare facilities should be in locations that are easily accessible on foot, by cycling or using public transport’. Given the space constraints in much of the city, ‘the plan encourages innovative design solutions’ (para 5.3.10).

‘Policy S4 play and informal recreation’ sets clear goals for local planning authorities stating that boroughs should, ‘prepare development plans that are informed by a needs assessment of children and young person’s play and informal recreation facilities.’ These assessments should include an audit of existing provision and policies should be supported by play and recreation strategies to address identified needs.

The London Plan recognises that play is essential for children’s mental and physical health. It makes a differentiation between formal and informal play areas, and the differences in provision required for different ages. Importantly the plan recommends that when preparing needs assessments, boroughs should consult with children and young people to ensure their needs are understood in terms of existing and future provision.

The London Plan was informed by ‘Making London child-friendly: Designing places and streets for children and young people[112]’, published in 2020. This document will also be used as part of the evidence base for the upcoming new supplementary planning guidance (SPG) on child-friendly approaches to city making, including independent mobility, play and recreation.

The London Plan has taken a child-friendly focus for several reasons. Two million of London’s residents are aged under 18 and 40% of whom are overweight or obese. There are huge variations in economic prosperity across the city that affect young people’s health, educational and employment opportunities. Children have been shown to be more vulnerable to the impact of environmental issues like London’s often poor air quality.

Importantly the deputy mayors forward to the ‘Making London Child-friendly’[113] says, ‘a London that works well for children and young people will be a London that works well for all of us …. we must move away from an approach that is just about ‘play provision’ and embrace the potential of London’s urban environment to plan and design spaces that put children and young people first.’

The approach of embedding child-friendly planning policies can be taken for any type of plan – regional, local, neighbourhood or masterplan.

Case study: Publish supplementary planning advice on children – London Borough of Hackney

The inner London Borough of Hackney is taking a pro-active approach to embedding child-friendly policies within its planning department. The Local Plan 2033[114] was adopted in July 2020. It contains several policies that directly relate to the needs of children, (including LP8 Social and Community Infrastructure, LP41 Liveable Neighbourhoods and LP50 Play Space). A Child-Friendly Places: Supplementary Planning Document (SPD)[115] supports the consideration of children and young people in the wider local policies in the plan (including LP9 Health and Wellbeing, LP42 Walking and Cycling and PP1 Public Realm). The impetus for taking a child-friendly approach has come from the Mayor of Hackney in the commitment made in their 2018 manifesto. Political support remains in place.

The inner London Borough of Hackney is taking a pro-active approach to embedding child-friendly policies within its planning department. The Local Plan 2033[114] was adopted in July 2020. It contains several policies that directly relate to the needs of children, (including LP8 Social and Community Infrastructure, LP41 Liveable Neighbourhoods and LP50 Play Space). A Child-Friendly Places: Supplementary Planning Document (SPD)[115] supports the consideration of children and young people in the wider local policies in the plan (including LP9 Health and Wellbeing, LP42 Walking and Cycling and PP1 Public Realm). The impetus for taking a child-friendly approach has come from the Mayor of Hackney in the commitment made in their 2018 manifesto. Political support remains in place.

The planning team has structured consideration of the public realm by dividing the neighbourhood into three scales: at the doorstep, the street and destination. By applying a child-friendly lens the planners have worked to address all aspects of the way children experience life in Hackney. Preparation of the SPD has included input from established links with young people, community groups, a cross council service working group, design professionals and experts in the field. Youth engagement workshops with the Hackney Youth Parliament, facilitated by ZCD Architects and the Hackney Young Future Commission informed the key principles and design guidance. The engagement found that teenagers often do not feel welcome in public spaces.

An internal working group, with representatives from planning, regeneration, street scene, family and children's services, public health, parks, arts and culture, urban design and education departments have ensured that a collaborative approach across the whole of the council has been taken. The outcomes will be utilised not just by the planning department, they will be embedded throughout all service areas of the council as best practice.

The child-friendly design guidelines in the SPD are centred around eight principles. These include shaping my borough, play on the way, people before cars, streets for people and contact with nature. The SPD includes tools for delivery and implementation, such as the child-friendly design checklist standard. Where ten characteristics of locations at the three different scales can be assessed by a traffic light system. It is in a clear and user-friendly format, that the public and stakeholders can easily understand and engage with. All larger schemes will be expected to submit a child-friendly impact assessment statement. The statement should be submitted as early as possible in the development process, so the improvements it highlights can be integrated into the final design.

The child-friendly design guidelines in the SPD are centred around eight principles. These include shaping my borough, play on the way, people before cars, streets for people and contact with nature. The SPD includes tools for delivery and implementation, such as the child-friendly design checklist standard. Where ten characteristics of locations at the three different scales can be assessed by a traffic light system. It is in a clear and user-friendly format, that the public and stakeholders can easily understand and engage with. All larger schemes will be expected to submit a child-friendly impact assessment statement. The statement should be submitted as early as possible in the development process, so the improvements it highlights can be integrated into the final design.

Lizzie Bird, Acting Deputy Manager, Strategic Planning at Hackney said, “Our hopes for the SPD are that it will help towards improving social equity and inclusivity within the borough”. It is expected to do this by informing several aspects of the LPAs work, including determining planning applications, area and estate regeneration plans, along with park and street scene initiatives.

The development of a draft SPD to support a newly adopted local plan in such an integrated way is an innovative and proactive approach by Hackney planning department and sets a precedent that other LPAs could follow.

Case study: Use child-friendly programmes to initiate action – London Borough of Redbridge

The Child Friendly Cities Initiative (CFCI) is led by UNICEF. It supports local government around the world to realise the rights of children at the local level using the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child[116] as its foundation. Child Friendly Cities aims to strengthen social inclusion, promote child and youth participation and change priorities in local decision making. It allows local authorities to focus on the areas of work that are most applicable to them. The programme has three phases: discovery, development and implementation, with the commitment expected to last for several years. A number of cities in the UK have signed up to the initiative.

The London Borough of Redbridge signed up to the initiative[117] in 2019. The planning team have a key role in delivering Child Friendly Redbridge[118]. During the discovery phase Redbridge spoke to more than 2,000 children and young people through a combination of questionnaires designed by children, lesson plans drafted by teachers and face to face focus groups. They also spoke to a range of other partners, including schools, police, National Citizen Service and Barnardo’s, as well as using data from open sources. The discovery phase found that the schools, libraries and children’s centres were viewed positively, as were the parks and green spaces. Most of the children and young people liked the area they lived in. However, it also found that knife crime is a big issue and young people feel unsafe in some parts of the borough. This includes young women and girls who are harassed. The feedback also showed that young people think that there are not enough places for them to go. Environmental issues were also a concern with pollution, litter and traffic, in particular, outside schools being seen as being dangerous and unhealthy for children.

The Planning and Building Control team are implementing a set of measurable actions that feed into CFR initiative. These include embedding the UNICEF principles into the planning application process. This is being implemented by identifying opportunities to engage with youth groups on the design of developments as part of the consultation process. A pilot scheme that examines the public realm of a large supermarket with youth groups is underway.

A review of the local plan[119] will take place in 2022. This provides an opportunity for the planning team to embed the CFR aspirations within the future engagement process and planning policies. The planning team will engage with young people on planning through existing, established mechanisms. These include Child Friendly Redbridge Ambassadors, Youth Council, SEND Youth Forum, Children in Care Council, Young Carers and others such as schools and youth clubs. Care is being taken to ensure engagement across the borough is coordinated, to guard against consultation fatigue. Community Design Forums are due to be established across the borough. These will encourage residents to opt into a forum to be kept up to date with ongoing developments or consultations for their local area. The forums will be promoted via schools and to youth groups to ensure a diverse membership.

A future goal is to develop a design guide for developers based on the UNICEF principles. The planning team recognises that applicants must currently refer to multiple policy and supplementary planning documents to ensure that the boroughs aspirations are met. To encourage child-friendly development they are aware they need to make the process of doing so as simple as possible.

Brett Leahy, Head of Planning and Building Control said, “It is still early days for Redbridge in terms of becoming a Child Friendly City, but the planners are excited about the prospects that it brings. It presents real opportunities for levelling up. It also presents challenges and relies on the local authority embracing change to deliver services differently with a focus on prevention rather than treatment to achieve tangible outcomes.”

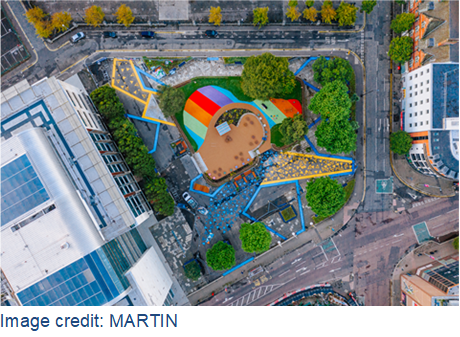

Case study: Create welcoming city centre spaces for children - Cathedral Gardens, Belfast

Cathedral Gardens is in Belfast city centre. It has been redesigned as a temporary landscaped area with a pop-up play park and family-friendly zone, as part of Belfast City Council’s wider city regeneration programme. The site it was previously a neglected space, with hard landscaping and anti-social behaviour. It was opened in 2020, during the Covid-19 pandemic as a meanwhile use for two years as a trial of how to reimagine civic spaces in the city to encourage innovative use of sites.

Cathedral Gardens is in Belfast city centre. It has been redesigned as a temporary landscaped area with a pop-up play park and family-friendly zone, as part of Belfast City Council’s wider city regeneration programme. The site it was previously a neglected space, with hard landscaping and anti-social behaviour. It was opened in 2020, during the Covid-19 pandemic as a meanwhile use for two years as a trial of how to reimagine civic spaces in the city to encourage innovative use of sites.

Belfast City Council and the Department for Communities provided £300,000 of funding. Although this is a significant investment for a temporary project, it was recognised that there was a need to provide more welcoming and open spaces for children. As a post-conflict city, Belfast is continuously changing, and the play park was designed to help bring communities together particularly from surrounding areas and promote the use of a shared city centre space. It follows the Council’s shared space principles that aim to create welcoming, safe, accessible and well-designed areas.

Consultation on the Cathedral Gardens project took place over four months, and it was designed with input from children at family friendly events including Belfast’s Culture Day and Night. Children were encouraged to outline their wish list for the site, which included unicorn grass and Parkour elements, both of which have been included in the final design. A brightly coloured palette was selected to appeal to children and the site is fully accessible with ramps to the equipment and sensory play opportunities.

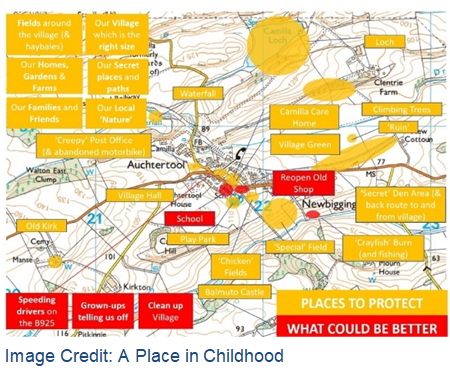

Consultation on the Cathedral Gardens project took place over four months, and it was designed with input from children at family friendly events including Belfast’s Culture Day and Night. Children were encouraged to outline their wish list for the site, which included unicorn grass and Parkour elements, both of which have been included in the final design. A brightly coloured palette was selected to appeal to children and the site is fully accessible with ramps to the equipment and sensory play opportunities.